In the fall of 1965, a twenty-nine-year-old Georges Perec published his début novel. Short and strange, “Things: A Story of the Sixties” follows Sylvie and Jérôme, a young Parisian couple who work in the burgeoning field of market research, and exist in a permanent frenzy of hyper-specific material desires. They want to furnish their apartment with fitted carpets, a black leather sofa, tartan-upholstered benches, “allegedly rustic tables.” They favor apparel that seems posh and British. Throughout the novel, the two characters are fused into a single entity—we never hear them speak—and they move through a world spangled with commercial temptations, insistently and precisely identified.

Like many before them, Sylvie and Jérôme mistake their pursuit of taste for a pursuit of knowledge, and believe themselves to be acquiring a kind of legibility—to others and to themselves. Theirs is, in effect, “the most idiotic, the most ordinary predicament in the world.” By the novel’s penultimate page, the couple’s notion of happiness—a permanent equilibrium between means and desires—has proved impossible to maintain, and they are en route to Bordeaux, where they have taken executive-level jobs at a second-tier advertising agency. The book ends with a kind of defeated sigh: they are but “tame pets, faithfully reflecting a world which taunted them.”

Still, Sylvie and Jérôme would be envied by Anna and Tom, a pair of similarly obedient animals at the center of the svelte new novel “Perfection” (New York Review Books). In the acknowledgment, its author, the Italian writer Vincenzo Latronico, calls “Perfection” a tribute to “Things,” and his protagonists are naïvely wistful for the past. “Previous generations,” Anna and Tom are convinced, “had had a much easier time working out who they were and what they stood for.”

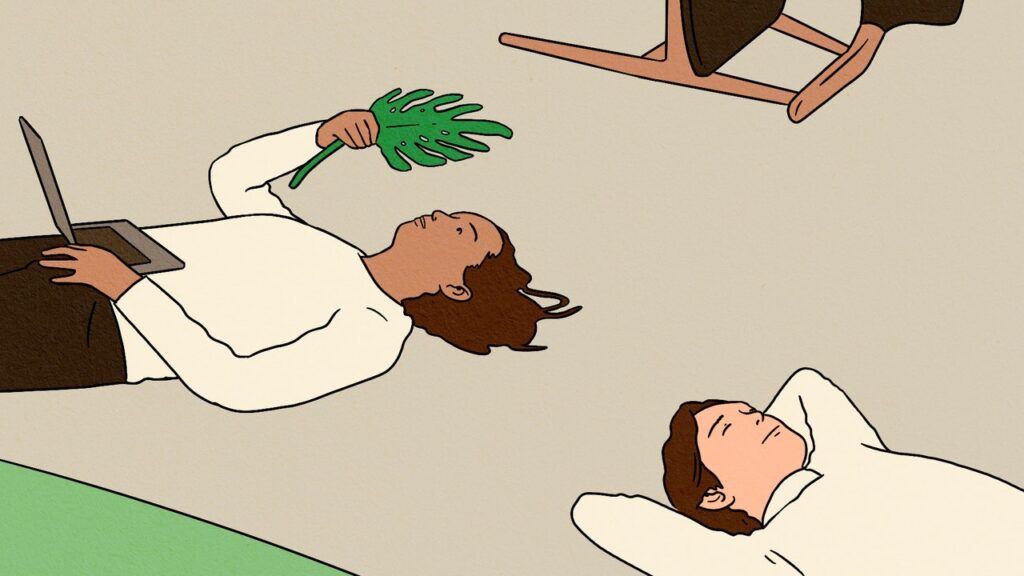

Like Sylvie and Jérôme, Anna and Tom move as one: they talk neither to each other nor to anyone else, and travel through a world littered with the supposedly-quiet-but-actually-quite-loud cultural signifiers of intellectualized upward mobility (houseplants, hardwood floors, unread back issues of this magazine). Latronico documents their decisions and demurrals with an elegant proportion of sly commentary to detached reportage, a ratio that Perec once described as “passionate coldness” and credited to Flaubert.

Latronico’s conceit is clever and will delight anyone familiar with his source material, but his execution is ingenious. In lieu of the Left Bank in the nineteen-sixties, we have Berlin in the twenty-tens, where Anna and Tom have moved from an unnamed country in southern Europe to pursue an art-adjacent life style and careers in graphic design. Like the laptops on which they work and play, Anna and Tom’s aesthetic preferences are always on the brink of obsolescence, and checking for updates is a full-time, if passive, occupation. Just as Sylvie and Jérôme’s work in mid-century advertising was a job that “history had chosen for them,” Anna and Tom’s status as creatives (“a term even they found vague and jarring”) is “a natural consequence of the context in which they had grown up.” As teen-agers who came of age with the internet, they doinked around on the computer and had fun doing so; as adults, they do for money what they once did out of passion. “This was a fact,” Latronico writes. “From this fact they concluded that they had turned their passion into a job. This was a deduction.” (Also a deduction: that his novel’s agility in English owes much to its talented translator, Sophie Hughes.)

Anna and Tom are not happy, even though nothing bad ever happens to them. Their worst misfortune is the cancellation of a freelance contract, which sets them back a few weeks financially. Nobody gets sick. Nobody dies. They have no dependents. They are so insulated from catastrophe and discomfort that they have to seek these things out. For a brief spell, they join the creative class of Berlin in mobilizing on behalf of a recent influx of migrants, whose arrival, in the summer of 2015, they first register not on the streets of the city where they live but as a chromatic shift on their computer screens, the familiar beige of Middle Eastern wars replaced by the silver of capsized dinghies amid Mediterranean azure. Anna and Tom find it hard to be useful, and although they are driven to help by a sense of civic obligation—“of course”—they are also motivated by “the feeling that something was taking place around them they didn’t want to miss, an outstanding rendezvous with history.”

But their entire life is organized around and enabled by a history that largely remains in their peripheral vision. They work at a job with no set hours in a country whose language they do not speak. They live in a light-flooded, plant-filled apartment whose location was determined decades before by the Allied bombings, though “it never occurred to them.” They travel frequently, and, when they do, the costs are partially offset by the fact that they can rent out their enviable apartment for a hundred and eighteen euros a night, “plus the fee to cover the Ukrainian cleaner, paid through a French gig economy company that files its taxes in Ireland; plus the commission for the online hosting platform, with offices in California but tax-registered in the Netherlands; plus another cut for the online payments system, which has its headquarters in Seattle but runs its European subsidiary out of Luxembourg; plus the city tax imposed by Berlin.”

Like “Things,” “Perfection” contains no dialogue, the characters existing almost post-verbally, as though the images they create and curate and consume on social media might speak for them. But do they?

In “Things,” this barrage of stimuli takes the form of page-filling questions that Sylvie and Jérôme pose to prospective customers:

Premium IPTV Experience with line4k

Experience the ultimate entertainment with our premium IPTV service. Watch your favorite channels, movies, and sports events in stunning 4K quality. Enjoy seamless streaming with zero buffering and access to over 10,000+ channels worldwide.