In Project Mind Control, John Lisle reveals inside story of the CIA’s secret mind control project, MKULTRA. Read on for a featured excerpt.

Prologue

On September 25, 1980, Rosanna Del Guidice arrived thirty minutes early to an office building in downtown Boston. Inside were cubicles, a small dining area, and, most importantly, a conference room where the depositions occurred. Rosanna was a court reporter. By typing on a stenograph machine, she converted the spoken word into written text as fast as her clients could talk.

Rosanna had always dreamed of being a teacher, but when she learned that teachers made “garbage money,” as she said in a later interview, she changed career plans. She briefly worked as a legal secretary making $1.63 an hour. On seeing an ad for a court reporting school offering its graduates six times as much, she enrolled against her father’s advice, graduated in 1972, and became one of the few female court reporters in New England.

The work was overwhelming, at least in the beginning. Rosanna cried after her first deposition because she couldn’t keep pace with the attorney’s relentless questions. “I didn’t know anything about the setup,” she said. “I didn’t know what the hell I was doing. That’s how it all started.” For the rest of the year, “I prayed my way through half of the depositions.”

Pretty soon, however, she gained enough confidence to become one of the fastest and most trusted court reporters in the industry, despite the discrimination that she faced as a woman. Attorneys would often ask her to do clerical work, something that they never asked of the male court reporters. “I don’t make copies,” she would tell them with a straight face. “Get your secretary in here.” In fact, she often earned twice as much money as the attorneys did for the day’s work.

In 1978, Rosanna experienced one of her most memorable days on the job. The case involved a group of photofinishers—the people who develop photographic film—who were suing the Kodak film company because their customers kept returning photos with red-eye. The photofinishers maintained that the problem was with Kodak’s equipment, and therefore Kodak should be held financially responsible. Kodak maintained that the problem was with the photofinishers’ development process, not the equipment, and therefore, the photofinishers should be held financially responsible. Millions of dollars were on the line.

A Kodak attorney had told the company’s scientists to keep their mouths shut during their depositions, but one elderly scientist slipped up and accidentally revealed that he had known about a problem with Kodak’s equipment. On hearing this, the attorney demanded to adjourn the deposition, an obvious attempt to silence the scientist. The photofinishers’ attorney yelled, “You’re not taking a break now, we’re in the middle of questioning!” Each side began shouting obscenities back and forth. In the heat of the moment, the Kodak attorney grabbed his counterpart by the necktie and dragged him across the conference table, leading to an all-out brawl. Rosanna, caught in the middle of it, clutched her stenograph machine and ran out to the hallway. “I’ll never forget it to the day I die,” she said. “The old scientist blew the case, all because he told the truth!”

* * *

Rosanna had arrived at the Boston office building thirty minutes early to arrange the conference room just how she liked it. She positioned herself at the head of the heavy wooden table. To her left would sit the attorney asking the questions; she wanted him as close to her ear as possible. To her right would sit Sidney Gottlieb, the deponent, whom she would turn to face. “I can’t tell you how much I learned to read lips. You can’t miss a beat.”

At 10:00 A.M., Gottlieb entered the conference room. Small in stature and with stark white hair, he didn’t want to be there, but he had no choice. Weeks earlier, a U.S. marshal had handed him a subpoena requiring him to provide a deposition in an ongoing case. Seven prisoners from the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary were suing the government for using them as guinea pigs in secret drug experiments. One prisoner described his experience in Atlanta as involving “horrible periods of living nightmares.” Another tried to kill himself by hanging, burning, and chewing off his own arm.

Once the attorneys arrived, everyone sat in their respective seats. Rosanna swore in Gottlieb and the deposition began. Attorney Thomas Maddox initiated the direct examination.

“Dr. Gottlieb, you understand I represent Mr. Don Roderick Scott, who was an inmate at the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary in the late 1950s; is that correct, sir?”

Gottlieb, a stutterer whose condition worsened when he was nervous, shook his head up and down.

Maddox intervened, “You need to answer something verbal, so this young lady—she can’t record nods.”

“I do,” Gottlieb said. “I am trying to say yes.”

Maddox next asked Gottlieb to describe his educational background.

“Well, my PhD was from Cal. Tech…in something called bio-organic chemistry.”

Maddox then skipped to the crux of the issue: “When did you first begin your association with the Central Intelligence Agency?”

* * *

Over the next three years, Gottlieb sat for four additional depositions conducted by legendary civil rights attorney Joseph Rauh and his young law partner James Turner. All four depositions took place in Culpeper, Virginia—one at a Holiday Inn, the other three at the Boxwood House Motel. The five total depositions lasted a combined twenty-five hours and consist of 823 pages of material. Many of Gottlieb’s colleagues sat for depositions of their own, as did many of their victims, constituting thousands more pages.

These newly discovered depositions provide a window into Gottlieb’s and his colleagues’ inner thoughts about their participation in some of the most controversial projects ever undertaken in the history of the CIA, projects that involved sex, drugs, torture, hypnotism, electric shocks, chemical comas, sensory deprivation, and assassination attempts. In short, the depositions represent a foray into the minds of those who perpetrated, as well as those who suffered, these infamous acts.

Upon rereading the transcript of Gottlieb’s first deposition, Rosanna said that he had revealed “a lot more than I would have expected.” While most people tend to conveniently forget their memories whenever they have an incentive to do so, Gottlieb, to her surprise, “was pretty open. His answers were so long. I was fascinated.”

Paul Figley, an attorney for the Department of Justice, had been present at another of Gottlieb’s depositions and reached a similar conclusion. In an interview, he said that Gottlieb “was going to tell the story that he wanted to tell. He had retired at that point and was going to do whatever he wanted to do, maybe what he had done his whole life.”

When asked whether Gottlieb had provided more information than was advisable from the perspective of a defense attorney, Figley took a long pause. “He was not as—” Another pause. “I didn’t have as much control over him as I would have liked.” He continued:

In a deposition setting, what you really want if you’re defending is for your client to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth about the question that is asked, and not to then go on and say, “This might be of interest to you” or “When I did that I thought . . .” It just opens up more areas and will lead to more rocks that people will have to turn over and see what’s underneath. He was not the kind of witness that if you’re defending a case you want to have because you don’t know what he’s going to say.

From the defense’s perspective, Gottlieb’s depositions were a disaster. From the historian’s perspective, they’re a gold mine.

1: The Outsider

Sidney Gottlieb had a number of unusual quirks. Most noticeably, he walked with an awkward limp, the result of two clubfeet. He also talked with a stutter. It wasn’t too pronounced—unless he was nervous—but when he was young, it gave his classmates yet another reason to tease him. From an early age, Gottlieb felt like an outsider.

His other quirks were self-inflicted. Throughout his life, he was known to drink goat milk, tinker with gadgets, and perform unusual dances to folk music.

Born in New York City on August 3, 1918, to Orthodox Jewish immigrants from Hungary, Gottlieb was an extremely bright child. When his older brother, David, built a makeshift laboratory in the basement of their brick house, Sidney developed a lasting love for science. He attended elementary and high schools in the Bronx, then jumped between colleges—City College of New York, Arkansas Polytechnic College, the University of Wisconsin—where for once in his life he apparently fit in. The Arkansas yearbook called him “a Yankee who pleases the southerners.”

At the University of Wisconsin, Gottlieb studied under the renowned bacteriologist Ira Baldwin. “Mr. Gottlieb is a very high type of Jewish boy,” Baldwin wrote in a glowing letter of recommendation. “He has a brilliant mind, is thoroughly honest and reliable, and is modest and unassuming.” Baldwin also mentioned that Gottlieb had “a slight speech impediment.”

After earning a bachelor’s degree in chemistry in 1940, Gottlieb enrolled in graduate school at the California Institute of Technology. Young, trim, and talented, he not only excelled in his coursework but also met the love of his life, Margaret Moore, who was studying preschool education at nearby Whittier College. Margaret had grown up in India, where her father was a Presbyterian missionary. To her father’s chagrin, she was a freethinker who questioned the morality of missionaries as well as the claims of Christianity.

Although Gottlieb and Margaret had been raised in completely different cultures on completely different continents, they shared the same eccentric spirit. In 1942, they married in a small civil ceremony. Margaret’s mother, accustomed to her daughter’s rebellious ways, wrote to her relatives, “If they have Each Other, they are indeed fortunate in this world full of sorrow.”

* * *

The United States had just entered World War II, and like many young American men, Sidney Gottlieb felt a sense of patriotic duty to fight for the country that had given his immigrant parents a second start at life. As soon as he earned a PhD in biochemistry in 1943, he tried to enlist in the Army. His limp, however, disqualified him from service. “I wanted to do my share in the war effort,” he later said, “yet I couldn’t convince anyone that I would not be hampered in my performance.” The rejection was one of the major disappointments of his life because it seemed to legitimize his long-held belief that he was an outsider. Gottlieb may have been unconventional by nature, but he nevertheless craved acceptance.

Over the next eight years, Gottlieb worked brief stints at the Department of Agriculture, the Food and Drug Administration, the National Research Council, and the University of Maryland, mostly developing tests to detect drugs in the human body. The jobs, he said, “became repetitive and sometimes pretty monotonous. I needed more of a challenge.”

Meanwhile, his personal life was full of excitement. He and Margaret soon had their first two children, both girls. The family of four (eventually six with two more little boys) moved into a remodeled former slave cabin in Virginia that had no water, electricity, “or any of that fancy stuff,” Margaret wrote in an autobiographical essay. “It sat under three very magnificent oak trees, and when I saw it, I said, ‘This will be my home.’ Sid, having grown up in New York City, thought I was nuts, but I persuaded him that I knew how to live this way.” Despite his initial skepticism, Gottlieb quickly adjusted to the primitive lifestyle. “Sid is pitching in more than he ever has before and he’s wonderful. I feel guilty sleeping when he has to milk the goats.”

Once his family was settled, Gottlieb began looking for a new job that was both intellectually stimulating and of service to his country. He might have been prevented from fighting in World War II, but his sense of patriotism was as strong as ever, especially at the outset of the Cold War.

* * *

The United States and the Soviet Union had shared an uneasy alliance during World War II. After the war, their alliance crumbled, prompting the onset of the Cold War, a decades-long period of geopolitical tension between the two countries. Contributing to the tension was the fact that many aspects of Soviet society—atheism, communism, slave-labor gulags, the dissolution of democratic institutions—seemed incompatible with American values.

Several other important world events further heightened the sense of tension. For one, the Soviets blockaded West Berlin in an attempt to extend their control over Germany. They also detonated their first atomic bomb, ending the American nuclear monopoly. Moreover, Mao Zedong and the Chinese Communist Party defeated the Chinese Nationalists in their civil war, and Communist North Korea invaded South Korea, initiating the Korean War.

Many Americans feared that Communists would next try to overthrow the government of the United States. As a result of this “Red Scare,” blacklists, loyalty oaths, and book bans spread across the country. (The children’s story Robin Hood was a notable target because it glorified stealing from the rich to help the poor.) Congress even passed anti-Communist legislation, such as the McCarran Internal Security Act, which barred suspect individuals from obtaining citizenship, holding passports, working in government jobs, and, in some cases, traveling to and from the country. At the state level, the Texas legislature made Communist Party membership a felony punishable by twenty years in prison. Governor Allan Shivers hesitated to sign the bill because of the punishment; he thought that the death penalty was more appropriate.

Conservative politicians capitalized on the Red Scare. In a gambit of political theater known as McCarthyism, they would accuse anyone with even the most tenuous connection to left-leaning causes of being a card-carrying Communist. The sensational nature of the accusations, regardless of whether they were true, generated fear, which generated press coverage, which generated votes for the politicians on Election Day. Journalist George Reedy joked that the eponymous Wisconsin politician Joseph McCarthy “couldn’t find a Communist in Red Square. He didn’t know Karl Marx from Groucho Marx.” Nevertheless, McCarthy recognized an opportunity to advance his political career when he saw one, even if it meant that he had to invent an enemy to fight.

Politicians weren’t the only ones exploiting the Red Scare. If the Navy wanted new ships, it exaggerated the threat of Soviet ships. If the Air Force wanted new bombers, it exaggerated the threat of Soviet bombers. The CIA once bought thousands of subscriptions to The Daily Worker, a Communist Party mouthpiece, in an effort to inflate the apparent circulation of the newspaper. If the Soviet Union was seen as powerful, the logic went, then Congress would give the military and the intelligence community more money to help defend the United States. And it worked.

A good portion of the Red Scare was manufactured for the benefit of a few individuals, companies, and organizations, but there still existed many people, for many good reasons, who believed that the Soviet Union represented an existential threat to the United States. Sidney Gottlieb was one of them.

* * *

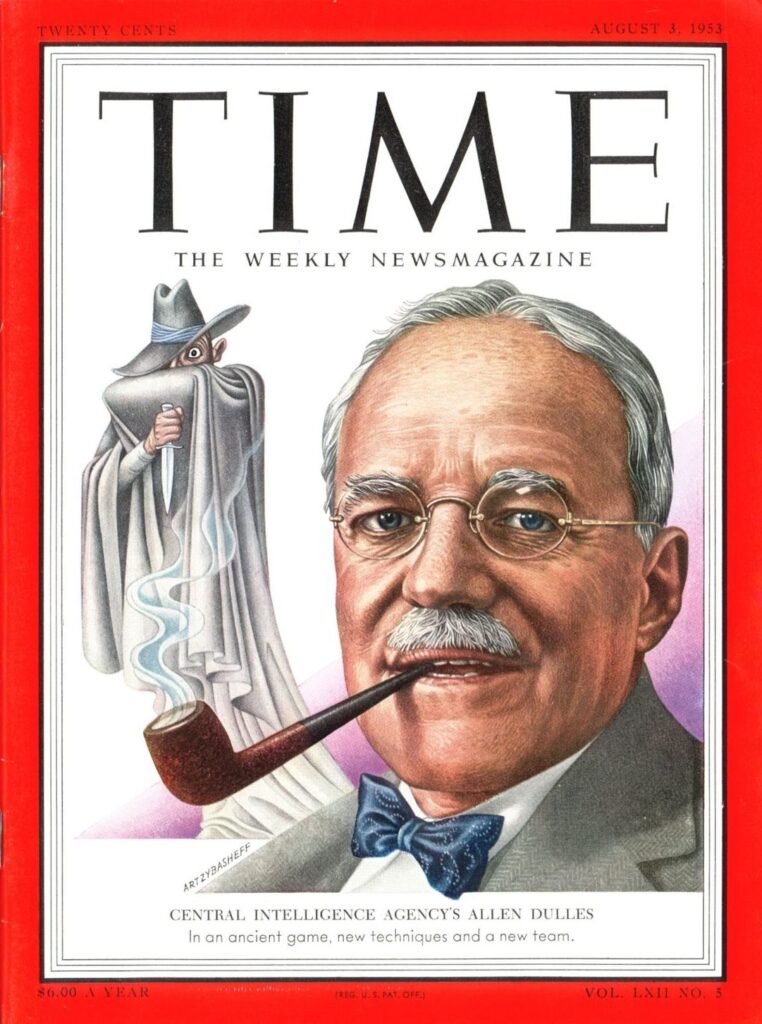

At the height of the Red Scare, Gottlieb’s patriotism drove him to apply for a job at the CIA, where he thought that his scientific expertise would compensate for his physical shortcomings. The CIA had been created in 1947 to coordinate American efforts to gather and analyze intelligence. President Harry Truman noted that the original CIA “was not intended as a ‘Cloak & Dagger Outfit’” that engaged in sabotage, assassinations, and other covert operations. Rather, it was “intended merely as a center for keeping the President informed on what was going on in the world,” though that would soon change.

Enabling the change was a series of laws that gave the CIA an unprecedented lack of oversight. Most notably, the Central Intelligence Agency Act of 1949 gave the CIA the ability to spend unvouchered funds and freed it from disclosing to Congress who its employees were and what they did. In other words, CIA personnel were emboldened to engage in covert operations because nobody was looking over their shoulders.

During the Red Scare, it was easy for those personnel to rationalize the need for covert operations. A government report on the CIA from the 1950s best summarizes their philosophy: “It is now clear that we are facing an implacable enemy whose avowed objective is world domination by whatever means and at whatever cost. There are no rules in such a game. Hitherto acceptable norms of human conduct do not apply.” Put simply, desperate times call for desperate measures.

Reflecting on the trajectory of the CIA, Truman lamented, “For some time I have been disturbed by the way [the] CIA has been diverted from its original assignment. It has become an operational and at times a policy-making arm of the Government. This has led to trouble and may have compounded our difficulties in several explosive areas.” In time, nobody would become more intimately acquainted with troublesome CIA operations in explosive areas than Sidney Gottlieb.

But in the summer of 1951, Gottlieb didn’t know much about the CIA. All he knew was that it was a place where he might repay the debt that he felt that he owed to his country. And to his good fortune, the CIA was looking to hire brilliant scientists like himself. The development of atomic bombs had shown that science was now an integral part of national security. The CIA needed someone like Gottlieb to explore the frontiers of knowledge and find new ways to win the Cold War, no matter how odd or esoteric.

* * *

Gottlieb was culturally, but not religiously, Jewish. Like so much else about his life, he would try to keep his beliefs shrouded in mystery. Margaret, on the other hand, was more forthcoming about her and her husband’s New Age sense of spirituality:

I am impatient when I hear people equate being “good” or “religious” with being Christian. There are many “goods” and many religions, and a Muslim’s way to God is very similar to ours, and so is a Hindu’s or a Buddhist’s, and I can’t see that Christianity is more full of love or less full of fears and superstitions…Is there a God? There is certainly a Force or a Source that all mankind (and maybe animals too) feels. It amazes and delights me that peoples who have not known of each other’s existence on the earth have come to very similar questions and to similar answers down through the ages since our very beginnings. There is Something that we all sense and are familiar with. Please let us not say, “My way is the only way.”

Given Gottlieb’s unique background and unorthodox beliefs, he once again felt like an outsider at the CIA, an organization whose workforce of affluent Ivy League graduates was often summarized as pale, male, and Yale. Gottlieb spent his first two years in the CIA working as a chemist for what was then called the Office of Policy Coordination, the division responsible for conducting covert operations abroad. While reminiscing in his depositions about this early work, he said that he had been involved in the “more classical application of chemistry to the intelligence field, things like secret writing, the use of chemistry in the printing process, areas like that.”

In 1953, he became the head of the Chemical Branch of the CIA’s Technical Services Staff (TSS). What did the TSS do? During one of Gottlieb’s depositions, attorney Thomas Maddox asked him, “Did [it] produce the gadgets and things we have associated with James Bond?”

“That’s the right idea,” Gottlieb said. “You are in the right ballpark.”

But both Maddox and Gottlieb knew that the TSS did much more than produce clever gadgets. Under Gottlieb’s direction, it conducted some of the most notorious projects in American history.

* * *

Throughout his depositions, Gottlieb stressed that in order to understand his work, it was necessary to understand the context in which it was done. At the beginning of the Cold War, the CIA had feared that Communist powers like the Soviet Union and China possessed methods of mind control powerful enough to manipulate a person’s beliefs and behaviors. One reason why the CIA feared such a thing was because Russian scientists had pioneered the field of behavioral conditioning. Back in 1897, Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov had shown that by ringing a bell every time that a dog ate, he could condition the dog to salivate at the sound of the bell alone. Surely the Soviets had since extended Pavlov’s work to include human subjects.

Another reason was because in the 1930s, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin had held a series of show trials in Moscow to remove his political opponents from power. Strangely, many of the defendants begged to be found guilty of the false charges levied against them. Yuri Pyatakov even prostrated before Stalin and asked for the honor of shooting his fellow defendants. (Perhaps his plea fell on deaf ears because his ex-wife was among the group.) Why were the defendants behaving so bizarrely? Had they been drugged? Had they been hypnotized? Had they been subjected to some other form of mind control?

Then, in 1948, Cardinal József Mindszenty, leader of the Catholic Church in Hungary and a vocal critic of the country’s new Communist regime, was arrested on charges of treason. Again, the charges were obviously false. The Communists were simply trying to silence one of their most influential critics. But at a show trial six weeks after his arrest, Mindszenty had somehow changed. He wasn’t his fearless, outspoken self. Instead, he appeared cold and unemotional. He didn’t even recognize his own mother when she came to visit him. Strangest of all, he confessed to the false charges. The image of this downtrodden priest, once so full of conviction, confessing to crimes that he didn’t commit caused many CIA personnel to wonder whether he had been subjected to mind control. “Somehow they took his soul apart,” said one intelligence officer.

In reality, Mindszenty confessed because he had been subjected to the more traditional methods of coercion: fatigue, hunger, torture, and isolation. Yet nobody in the CIA knew this for sure. Out of an abundance of caution, they assumed the worst. Maybe the Communists had perfected mind control. The recent success of dystopian novels like Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World and George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four certainly made it seem possible.

The Communist threat of mind control was considered so real that a CIA memo from the early 1950s recommended that all overseas employees based near the Iron Curtain avoid hospitalization, medical attention, and psychiatric treatment of any kind unless conducted by “fully authorized and trusted institutions and doctors.” The enemy might strike at any unguarded moment.

Such a fear wasn’t as strange as it sounds, and Gottlieb knew that it sounded strange. “All of this might seem farfetched now,” he said in his depositions. “But I would beg you to try to live in another context, namely that of 30 years ago, when it was—” He paused. “Things were thought possible then.”

Copyright © 2025 by John Lisle. All rights reserved.

Premium IPTV Experience with line4k

Experience the ultimate entertainment with our premium IPTV service. Watch your favorite channels, movies, and sports events in stunning 4K quality. Enjoy seamless streaming with zero buffering and access to over 10,000+ channels worldwide.