How should we understand miracles? Many people in the near and distant past have believed in them; many still do. I believe in miracles too, in my way, reconciling rationalism and inklings of a preternatural reality by means of “radical amazement.” That’s a core concept of the great modern Jewish philosopher Abraham Joshua Heschel. Miracles, insofar as Heschel would agree with my calling them that—it’s not one of his words—do not defy the natural order. God dwells in earthly things. Me, I find God in what passes for the mundane: my family, Schubert sonatas, the mystery of innate temperament. A corollary miracle is that we have been blessed with a capacity for awe, which allows us “to perceive in the world intimations of the divine, to sense in small things the beginning of infinite significance,” Heschel writes.

Every so often, though, I wonder whether radical amazement demands enough of us. Heschel would never have gone as far as Thomas Jefferson, who simply took a penknife to his New Testament and sliced out all the miracles, because they offended his Enlightenment-era conviction that faith should not contradict reason. His Jesus was a man of moral principles stripped of higher powers. But a faith poor in miracles is an untested faith. At the core of Judaism and Christianity lie divine interventions that rip a hole in the known universe and change the course of history. Jesus would not have become Christ the Savior had he not risen from his tomb. Nor would Jews be Jews had Moses not brought down God’s Torah from Mount Sinai.

Those who wish to engage with religious scriptures are not relieved of the obligation to wrestle with how miracles should be understood. Do we take them literally or symbolically? Are they straightforward reports of events that occurred in the world, perhaps ones that are no longer possible, because God no longer acts in it? Or are they encoded accounts of things that happened on some other, less palpable level, but were no less real for that?

In her book Miracles and Wonder: The Historical Mystery of Jesus, Elaine Pagels asks different questions about New Testament miracles. She is less interested in whether Jesus performed them than in what accounts for their power. Her larger quest is to understand the enduring appeal of Jesus to so many people “as a living presence, even as someone they know intimately.” Pagels, now 82, is a historian of early Christianity who also writes about her own efforts to find an experience of Christianity, a sense of intermittent grace, consonant with her experience of extreme loss: Her first son died at 6 of a rare disease; her husband died in a hiking accident shortly thereafter. She has spent a lifetime thinking about the multiple dimensions of the gospel truth.

Pagels’s The Gnostic Gospels (1979) is a liberal theologian’s cult classic—it has gone through more than 30 printings. Though not her first work of scholarship, it marked the beginning of a long career as a gifted explainer of abstruse ideas. Her overarching ambition has been to restore a lost heritage of theological diversity to the wider world. The Gnostic Gospels reintroduced forgotten writings of repudiated Jesus sects, produced over the course of the first and second centuries, before a welter of competing perceptions of Jesus’s story were reduced to a single dogma, codified in the apostolic creed, and before the New Testament was a fixed canon. Sounding faintly Buddhist to the modern ear, those writings interpreted miracles as symbolic descriptions of real spiritual revelations and transformations, available only to those with access to secret knowledge (gnosis). “Do not suppose that resurrection is an apparition,” one gnostic teacher wrote in his Treatise on Resurrection. “It is something real. Instead, one ought to maintain that the world is an apparition.”

The subtitle of Miracles and Wonder is slightly misleading: The Historical Mystery of Jesus seems to imply that Pagels will revisit the old debate over whether Jesus existed. That he did is settled doctrine, at least among historians. Rather, she takes us back to what biblical scholars call the Sitz im Leben, the “scene of composition,” in an effort to reconstruct where miracle narratives came from and how they evolved. Using the tools of the historian as well as the literary critic, she tries to unearth the writers’ concerns and influences, and she considers miracles from a bluntly instrumentalist perspective: What problems did they solve; what new vistas did solving them open; what religious function did they serve?

Among their other uses, miracles helped the evangelists overcome challenges to the authority of the Christ story. For all his enigmatic teachings and at times mystifying behavior, Jesus the man is not that hard to explain: He was one among many Jewish preachers and healers prophesying apocalypse in a land ravaged by Roman conquest and failed uprisings. But Jesus the man-god was more difficult for outsiders—Roman leaders, Greco-Roman philosophers, other Jews—to accept. They asked a lot of hostile questions. Why worship a Messiah whose mission had apparently failed? Didn’t his ignominious end—crucifixion was Rome’s punishment for renegades and slaves—contradict his claim to be divine? The Romans were incredulous that anyone would glorify a Jew. To the Jewish elite, he was a rube from the countryside.

Mark, the first known writer of a Christian gospel, could have produced a traditional hagiography. Instead, wishing to publicize Jesus’s singular power—to spread the “good news”—he appears to have invented the gospel genre, the Greek biographical novella as a work of evangelical witness; the subsequent chroniclers followed his lead. Writing around the time of the destruction of the Second Temple, in 70 C.E., he gave Jesus’s story cosmic dimensions. Now it was the tale of “God’s spirit contending against Satan, in a world filled with demons,” in Pagels’s words. Mark may have been recording oral stories developed by Jesus’s followers to convey perceptions of real experiences, but Mark, and they, would also have wanted to defend their certainties against the skeptics.

Pagels isn’t trying to shock the faithful. Reading sacred texts as the products of history, rather than the word of God, has been standard practice in biblical scholarship for more than a century. Her book demonstrates that the Wissenschaftliche, or “scientific approach” (the pioneering Bible scholars were German), doesn’t have to be reductive; indeed, critical scrutiny may make new sense of difficult texts and yield new revelations. As Pagels portrays them, the evangelists were men of creative genius, using their defense of Jesus as an occasion to draft the outlines of a new world religion. “What I find most astonishing about the gospel stories,” she writes, “is that Jesus’s followers managed to take what their critics saw as the most damning evidence against their Messiah—his crucifixion—and transform it into evidence of his divine mission.”

In some cases, recontextualizing the old stories gives them an unexpected poignancy. A good example is her analysis of the virgin birth. It yields a less sanctified Mary, but by highlighting darker currents in the text perhaps obscured by tradition, Pagels imbues the young mother with a haunting sadness. We think of the virgin birth as a basic element of Christian faith, yet only two of the four canonical Gospels refer to it: Matthew and Luke. Mark doesn’t mention Jesus’s birth and says little about his family background. When we first encounter Jesus, he’s a full-grown Messiah being baptized in the wilderness. John’s Gospel has a bit more on Jesus’s family, but no birth scene. When we first see Jesus in the Gospel of John, he is already both the Son of God and a man—that is to say, not an infant.

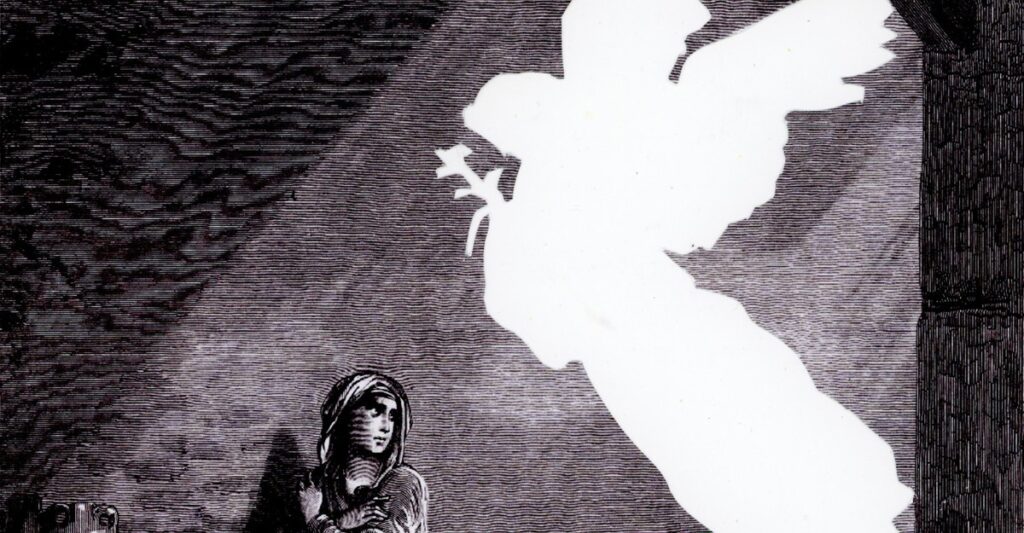

Matthew and Luke, by contrast, not only depict Jesus’s birth, but herald it at length. They supply genealogies that stretch back to King David, the founder of Israel’s dynasty, giving Jesus a lineage commensurate with his stature. Matthew stresses royalty, prefacing the birth with heavenly portents; afterward, Magi bear royal gifts to a future king. Luke’s version is more rustic but heightens the dramatic tension between Jesus’s humble background and his divinity. Joseph and Mary are turned away from an inn. Mary gives birth in a barn, and shepherds worship him. Both feature an Annunciation, in which an angel appears and announces that Mary, a virgin who is engaged to Joseph, is to have a son by God. In Matthew, the angel comes to Joseph, who has already discovered that Mary is with child, and advises him to marry her—he was planning to send her away before she disgraced them both. Luke’s angel goes directly to Mary.

Why did Matthew and Luke add all this material? Among the many possible answers, Pagels focuses on the likelihood that after Jesus’s death, talk began to circulate that he was the illegitimate son of an unwed mother. The second-century Greek philosopher Celsus used the charge to discredit the Gospels. In an anti-Christian polemic citing Jewish sources, he writes, “Is it not true … that you fabricated the story of your birth from a virgin to quiet rumors about the true and unsavory circumstances of your origins?”

That Mark himself seems to have called Jesus’s paternity into question complicates matters. When his Jesus comes home to Nazareth to preach at the local synagogue, his former neighbors mock him for his wild ideas. “Where did this man get all this?” they sneer. “What miracles has he been doing? Isn’t this the carpenter, the son of Mary, the brother of James, Joses, Judas, and Simon?” (The italics are Pagels’s.) Mark’s readers, who knew how Jewish patronymics worked, would have understood what the villagers were throwing in Jesus’s face. They would not have said “son of Mary” if they’d known the name of Jesus’s father—even if his father was dead.

Matthew and Luke excise that “son of Mary” and make Jesus not just legitimate but doubly legitimate. His mother acquires both a husband, Joseph, and a father, God, for her child. Her marriage and Jesus’s divine paternity purge the implied stain of wantonness. And yet disturbing hints of sexuality still run beneath the surface of the evangelists’ Gospels. In Luke’s Annunciation, after the angel Gabriel delivers his message, Mary asks, “How can this be, since I am a virgin?” Gabriel replies, “The Holy Spirit will come upon you, and the Power of the Most High will overshadow you.”

Pagels doesn’t cite this exchange or address the disconcerting aggressiveness of “come upon you” and “overshadow you,” but she does look closely at Mary’s response: “I am the Lord’s slave; so be it.” This is Pagels’s translation; the word she gives as slave, doule, is in this context more often translated as “servant” or “handmaid.” Soon after, Luke has Mary, thrilled about the pregnancy, burst into song. But her first response, Pagels says, sounds more resigned than joyous: “An enslaved woman was required to obey a master’s will, even when that meant bearing his child, as it often did.” At a minimum, “a girl with no sexual experience might be startled and dismayed to hear that she is about to become pregnant, given the potential embarrassment and shame she might suffer.”

Pagels goes so far as to conjecture how Mary got pregnant, a thesis very much based on circumstantial evidence. Around the time of Jesus’s birth, tens of thousands of Roman soldiers marched into Judea to suppress an insurrection, a brutal campaign recorded by the Jewish historian Josephus. As they fanned out through the countryside to hunt down rebels, they kidnapped and raped any women they could find. Pagels asks, “Was Mary, as a young girl from a humble rural family,” one of those women? “We have no way of knowing,” she adds, though she is struck by one coincidence. Unfriendly rabbinic sources from the first few centuries after Jesus’s death cited slanderous gossip claiming that Mary was promiscuous and had a lover who was a soldier named Panthera, and that he was Jesus’s father. Modern scholars have found the gravestone of a soldier with that name, said to have served in Judea until 9 C.E.; Pagels wonders whether he could have been one of those rapists. Thinking of Mary as a victim of sexual assault is horrifying; it feels sacrilegious. But that she gave birth to her son in an age of cataclysmic violence does make his ultimate triumph seem even more miraculous.

An appreciation of context also yields a new reading of the Passion of the Christ. This account of Christ’s trial and torture in the days leading up to the crucifixion, which shows the Jews baying for his death, has been thought by some to have contributed to centuries of anti-Semitism. In Pagels’s version, the evangelists are motivated less by sheer hatred of Jews than by the need to solve some difficult theological and political problems. What leads them to demonize the Jewish priests and elders, even as they turn Pontius Pilate, Judea’s Roman governor, into an honorable man who perceives Jesus’s innocence and is loath to sentence him?

That the leader of a notoriously cruel occupying power would have shown such compassion for a militant rebel strains credulity and defies the historical record. Pilate was infamous for his “greed, violence, robbery, assault, frequent executions without trial, and endless savage ferocity,” according to the first-century Jewish philosopher Philo, among many others. “I find no simple answer” to the conundrum of the revisionist Pilate, Pagels writes. But she has her theories. For one thing, by acknowledging Jesus’s innocence, the Pilate of the Gospels safeguards Jesus from the charge that he died a criminal.

A good Pilate is implausible though not impossible—that is to say, not miraculous—but he plays a crucial role in the larger miracle of the crucifixion, the transfiguration of a degrading death into the salvation of all mankind. Another reason for the evangelists to absolve Pilate of blame, according to Pagels, would have been to protect themselves. The Roman authorities persecuted Christians harshly, subjecting them to torture and deaths even more gruesome than crucifixion. To vilify a high Roman official was to invite retribution. As the Christians grew more Gentile, the Gospel writers made Pilate more sympathetic and the Jews less so. The writers could not have foreseen that their scapegoating of the Jews would have such lethal consequences and for so long.

I should stress that the Christian miracle narratives have multiple sources. Most important, they interpret other texts. Sure that Jesus was the Messiah, his followers scoured the Jewish Bible for prophecies that foretold his coming. The virgin birth elaborates on a verse from Isaiah that could be construed as predicting it: A virgin “shall conceive, and bear a son.” (“Virgin” is a famous mistranslation. The Hebrew word is almah, or “young woman.” But Matthew would probably have been reading the Hebrew Bible in Greek, where the word appears as parthenos, “virgin.” ) Drawing on existing holy writ was in no way scandalous. Even as Christians moved away from Judaism, the evangelists continued to work within a Jewish scriptural tradition that expected later writers to build on earlier ones. The presence of the old texts in the new ones served as validation. In Matthew and Luke’s view—and in the view of Christians throughout the ages—Isaiah proved them right.

What do biblical miracles do for believers today? In Pagels’s final chapter, she visits Christian communities around the world, many of them poor and subject to political oppression, to explore some of the ways in which the story of Jesus continues to offer comfort and inspiration. In the Philippines, for example, she finds the Bicolanos, Catholics living in remote villages, who worship a syncretistic Jesus inflected with Filipino tradition; they are particularly focused on Easter week, because to them, Jesus represents the promise of a glorious afterlife.

Miracle stories also have applications outside a strictly religious context. They are indispensable fictions, tales to live by. They re-enchant the world. Or so I feel. I read the Bible, Christian as well as Jewish, not for spiritual nourishment—or not for what is generally considered spiritual nourishment—but to be reminded that the universe once held more surprises than it does now and that hoping when all seems hopeless is not unreasonable, at least from the vantage point of eternity. Miracles are useful insofar as we take their poetry seriously. We are talking about encounters with the Almighty. Human language falters in the face of the indescribable, which reaches us only through the figures of speech we are able to understand.

This article appears in the May 2025 print edition with the headline “What to Make of Miracles.”

By Elaine Pagels

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

Premium IPTV Experience with line4k

Experience the ultimate entertainment with our premium IPTV service. Watch your favorite channels, movies, and sports events in stunning 4K quality. Enjoy seamless streaming with zero buffering and access to over 10,000+ channels worldwide.