Leonard Bernstein’s way with orchestras that wouldn’t give him what he wanted was usually imploring, even beseeching. He was disappointed—the musicians were not so much failing him, the conductor, as failing the composer, failing the music. But on one occasion, his disappointment turned to anger. In 1972, he was working with the Vienna Philharmonic on Gustav Mahler’s Fifth Symphony. Mahler had been the head of the Vienna Court Opera and had conducted the Philharmonic from 1897 to 1907.

This was their own music—and they were holding back. Bernstein was rehearsing the stormy first movement of the Fifth Symphony. In his own score of the work, now lodged at the New York Philharmonic Archives, he had written, before the opening movement, “Rage—hostility—sublimation by Mahler and heaven.” And then, “Angry bitter sorrow mixed with sad comforting lullabies—rocking a corpse.” But he was getting neither rage nor consolation from the Vienna Philharmonic.

Sighing and shrugging, irritably flipping pages of the score back and forth, he finally burst out (in German): “You can play the notes, I know that. It’s Mahler that’s missing!” The orchestra had arrived at the anguished climax toward the end of the movement, and the strings—by habit sweet and lustrous—were not playing with the harsh intensity that he wanted. “I’m aware that it’s only a rehearsal. But what are we rehearsing?” It was an implied threat to walk out.

Bernstein later reported hearing grumbling from the ranks. “Scheisse Musik.” Shit music. Scheisse Musik was Jewish music. Mahler was a Bohemian Jew. “They thought it was long and blustery and needlessly complicated and heart-on-sleeve and overemotional,” Bernstein said later in a documentary interview about his relations with the orchestra. The Philharmonic, after banning Mahler during the Nazi period, had played his great, tangled, tormented later symphonies only a few times. The orchestra didn’t know the music; the musicians didn’t love it.

The moment is startling because this was hardly Bernstein’s initial encounter with the esteemed Vienna Philharmonic. He had first conducted the orchestra in 1966, and with enormous success (bouquets were flung; champagne was poured), so his wrath carried a hint of betrayal, as if to say, “We are squandering a lot of hard work.” Turning Mahler into a universal classic—not just a long-winded composer of emotionally extreme symphonies—was part of Bernstein’s mission, part of his understanding of the 20th century, and essential to his identity as an American Jew. In their prejudice against Mahler, which was both racial and musical, the Germans and Austrians at the core of classical tradition had torn out of themselves a vital source of self-knowledge as well as musical glory. Destroying Mahler made it easier for them to become Nazis. Bernstein was determined to restore what they had rejected.

He was proud of America’s musical achievements—proud of the work of the composers Charles Ives and Aaron Copland, and perhaps even prouder of the enduring native talent for popular Broadway entertainment, which, in 1972, was largely a Jewish creation. He had ennobled that tradition himself with the galvanizing West Side Story and the brilliant potpourri that is Candide, an homage to Voltaire’s satire and to European operatic styles, shaped into the greatest American operetta. Ever eager to break down the barriers between classical and popular music, he put elements of jazz into his work. In the ’20s, Europeans had certainly become conscious of American jazz, and Bernstein wanted to enlarge that recognition; he wanted to join America to world culture, even world history.

It turned out that he needed the Vienna Philharmonic, and it needed him too. In fact, after the war, the orchestra needed him desperately. That angry rehearsal was a cultural watershed. Bernstein demanded that Vienna, and Europe in general, acknowledge what both America and Mahler meant to the 20th century—the century that the Europeans had played such a dreadful part in and that the Americans had helped liberate from infamy. An American Jew had become the necessary instrument in the New World’s reforming embrace of the disgraced Old.

The child of Ukrainian immigrants, Bernstein grew up in suburban Boston, an irrepressibly musical little boy who loved listening to the radio and beat out rhythms on the windowsills at home. He didn’t have a piano until he was 10. His father, Sam, notoriously refused to pay for piano lessons, but when he finally relented, Lenny accelerated to full speed, working with the best piano teachers in the Boston area, including the well-known German pianist Heinrich Gebhard. In the summers, he stayed at the family cottage in Sharon, Massachusetts. As a teenager there, Lenny mounted a production of Carmen in which he played the temptress, wearing a red wig and a black mantilla, and a tumultuous Mikado in which he sang the part of Nanki-poo.

Let me make a comparison with a renowned European musician. In 1908, Herbert von Karajan was born in Salzburg, Mozart’s birthplace. There were at least two pianos at home, and Karajan played through Haydn and Beethoven symphonies with his family. On special evenings, string and woodwind players among the family’s Salzburg friends would assemble at the house for chamber music. When he was 6, Karajan took classes at the Mozarteum, the school that preserved the Austro-German musical legacy. He spent his summers with his family on a stunning mountain lake, the Grundlsee, 60 kilometers east of Salzburg.

The contrast makes an American happy: on the one side, tradition, serious public performance, luxury; on the other, émigré teachers, amateur musicales and family shenanigans, casual summers in the modest countryside. Yet what Boston and its environs had to offer in the 1930s, however scrappy, was enough to bring out Lenny’s talent. Karajan was a prodigy; Bernstein was a genius.

On November 14, 1943, the 25-year-old American conducted the New York Philharmonic without rehearsal; the concert was nationally broadcast on CBS Radio, and Bernstein was famous by the next day. In the following years, he conducted all over the country while working on his own classical compositions, including his Symphony No. 1 (Jeremiah), based on biblical texts. By the time he was 40, in 1958, he had created the Broadway successes On the Town and Wonderful Town, in addition to Candide and West Side Story, as well as some of his enduring classical scores. In that same year, he took over as music director of the New York Philharmonic.

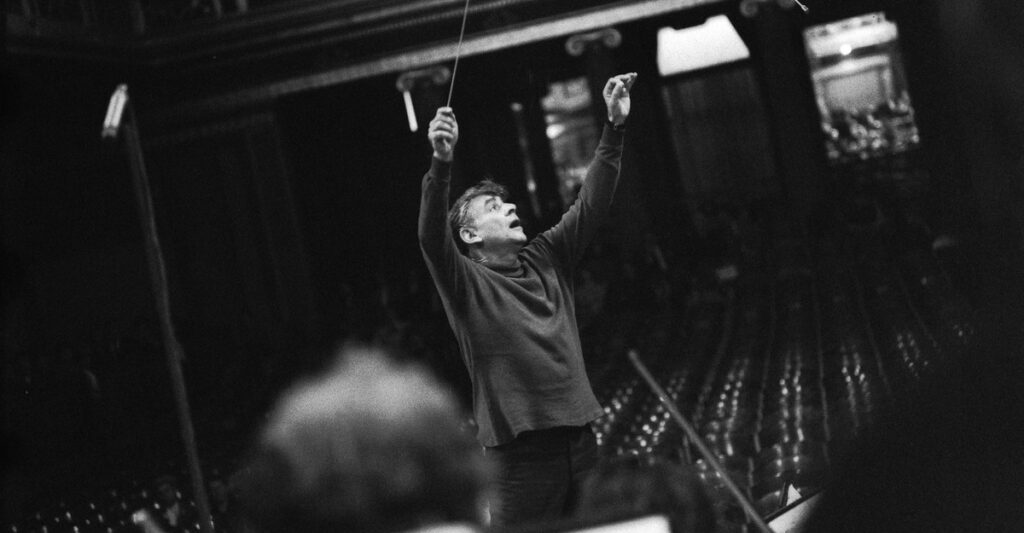

Initially, there was a lot of excitement in the press—the first American at the helm of one of the great orchestras! But the tone soon became hostile, even acrimonious. Audiences loved Bernstein, but his full-bodied manner on the podium—arms, head, hips, shoulders, eyebrows, groin in motion—caused embarrassment and even anger. The critic and composer Virgil Thomson, writing in the New York Herald Tribune, complained of “corybantic choreography” and “the miming of facial expression of uncontrolled emotional states.” In the arts, embarrassment may be the superego of emotion: This liberated Jewish body dismayed not only Thomson but the fastidious descendants of German Jews in New York, especially Harold C. Schonberg, the chief music critic of The New York Times starting in 1960, who gave Bernstein terrible reviews for years. In the eyes of Schonberg and others, Bernstein was hammy, exaggeratedly expressive, undignified: He was Broadway; he was show business; he lacked seriousness. The ecstasies of classical music are supposed to be, well, clean. But here was this lusciously handsome young man, a little overripe, leading orchestras in Haydn and Beethoven.

I went to a lot of Philharmonic concerts in Bernstein’s early days as music director, and I heard some things that were under-rehearsed and overdriven, a bit coarse, without the discipline and mastery that were so extraordinary in his later years. But the playing was always vital, the programs exciting. And one concert, given on April 2, 1961, changed my life. It was a performance of Mahler’s Symphony No. 3, a monster with six movements, 95 minutes of outrageously stentorian swagger and odd, folkish nostalgia, capped by a lengthy adagio marked Langsam. Ruhevoll. Empfunden (“Slowly. Tranquil. Deeply Felt”). Bernstein took the adagio at a very slow tempo indeed, considerably slower than did many subsequent conductors, who, I daresay, would have had trouble holding it together at that speed. But the tempo wasn’t remarkable in itself. What was remarkable was the sustained tension and momentum of the movement and the sense of improvisation within it—the slight hesitations; the phrases explored, caressed; and also the singing tone of the entire orchestra at those impossibly slow speeds, all of it leading to the staggering climax at the end.

The audience erupted into applause, and I remember thinking (I was 17), Anyone who doesn’t know that this man is a great musician can’t hear a thing—or something like that. (The Mahler Third was recorded within the next few days at the Manhattan Center, on West 34th Street. What I heard then, you can hear now on a Sony CD and a variety of streaming services.) After the concert, I went home shaken. That last movement opened gates of sensation and feeling that I had never experienced before, at least not outside of dreams. I was a very repressed and frightened teenager, and the music granted permission, a kind of encouragement to come out of myself and meet the world. The word awakening sounds banal, but I don’t know how else to describe what happened. Bernstein had that effect on many people. But it took his first engagement with the Vienna Philharmonic to awaken New York’s critics, which became one of the great ironies of American musical taste.

During that first stint in Vienna, in 1966, Bernstein conducted Verdi’s Falstaff (at the Staatsoper, the orchestra’s sister organization, formerly known as the Vienna Court Opera). With the Philharmonic, he also did some Mozart, along with Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde, the orchestral work for two voices that was in fact part of its repertoire. (It was the convoluted and violent later symphonies—masterpieces, all—that the orchestra resisted.) The ovations in 1966 went on forever, in a startling kind of release that even Bernstein, who certainly enjoyed acclaim, thought was a bit curious. “I’m a sort of Jewish hero who has replaced Karajan,” he wrote to his wife, Felicia. And a couple of weeks later, making a report to his parents:

You never know if the public that is screaming bravo for you might contain someone who 25 years ago might have shot me dead. But it’s better to forgive, and if possible, forget … What they call the “Bernstein wave” that has swept Vienna has produced some strange results; all of a sudden it’s fashionable to be Jewish.

The reference to Karajan was far from casual. The prodigious child of Salzburg had become a dominant figure in European classical music. In 1954, when he and Bernstein were both working at La Scala, they talked late into the night. Lenny wrote to Felicia: “I became real good friends with von Karajan, whom you would (and will) adore. My first Nazi.” (Karajan had joined the party in 1935 and remained in it until the end of the war.)

Bernstein’s way of appropriating ex-Nazis has elements of both seduction and triumph. When he went to Vienna in 1966, he had to deal with the repulsive truth that a man named Helmut Wobisch, a former trumpet player in the Philharmonic, was now the manager of the Philharmonic. Wobisch had worked for the SS during the war, and was likely involved in expelling Jewish members from the orchestra. Bernstein referred to him in public as “my dearest Nazi,” and there are photos of Wobisch happily greeting the maestro at the Vienna airport.

Bernstein made grim jokes, but he wanted to woo these men away from their past, their guilt; he would win them over, asserting not only Jewish talent but Jewish forgiveness. He and Karajan developed a friendly rivalry. On different occasions, when they were working in Vienna and Salzburg at the same time, they took turns upstaging each other in public. One was a perfectionist who gave performances of stunning power that sometimes became smoothed out and even bland through repetition; the other was full of surprises—always discovering things, a sensibility always in the making. For years, they represented two versions of musical culture: the authoritarian essence of the Old World and the democratic essence of the Jewish-immigrant New World.

That an American conductor of any kind was enjoying acclaim in Europe was itself cause for wonder. From Bernstein’s point of view, the odds had always been stacked against him. Some years after that 1966 triumph, he wrote the distinguished Austrian conductor Karl Böhm:

You were born in the lap of Mozart, Wagner and Strauss, with full title to their domain; whereas I was born in the lap of Gershwin and Copland, and my title in the kingdom of European music was, so to speak, that of an adopted son.

But by 1972, the positions of son and elders were reversed, and Bernstein’s tone as he fought the Vienna Philharmonic in that rehearsal of the Mahler Fifth was anything but abashed. Bernstein did not, of course, walk out of the turbulent session. He stayed, and he drove the Vienna Philharmonic hard. An American Jew would make them play this music.

In a 1984 video lecture called “The Little Drummer Boy,” Bernstein insisted that Mahler’s genius depended on combining two laughably incompatible musical strains—the strengths of the Austro-German symphonic line and the awkward and homely sounds of shtetl life recalled from the composer’s youth in Bohemia. The exultant and tragic horn calls in the symphonies and in Das Lied von der Erde—were these not the potent echoes of the shofar summoning the congregation on High Holidays? The banal village tunes that Mahler altered into sinister mock vulgarities—did these not recall the raffish klezmer bands, the wandering musicians who played at shtetl weddings?

The ambiguity, the exaltation and sarcastic self-parody, the gloom alternating with a yearning for simplicity and even for redemption—all of that reflected the split consciousness of Jews who could never belong and turned revenge upon themselves. In a remark that Bernstein often quoted, Mahler said, “I am thrice homeless. As a native of Bohemia in Austria, as an Austrian among Germans, and as a Jew throughout all the world. Everywhere an intruder, never welcomed.”

Mahler was demanding and short-tempered, and shame—the shame of being a Jew—may have been an element in his volatile disposition; Bernstein felt that it was. Leading orchestras in London, Tel Aviv, and Berlin, as well as in Vienna and New York, he performed the symphonies and song cycles with a violence and tenderness that ended any further talk of shame. By advocating for Mahler as powerfully as Bernstein did, he helped bring the Jewish contribution to Austro-German culture back into the lives of Europeans—and perhaps also a range of emotions, including access to the bitter ironies of self-knowledge that had been eliminated from consciousness during the Nazi period. Mahler died in 1911, but Bernstein believed that Mahler knew; he understood in advance what the 20th century would bring of violence and harrowing guilt. “Marches like a heart attack,” Bernstein wrote in his score of Mahler’s apocalyptic Sixth Symphony. The tangled assertion and self-annihilation, the vaunted hopes and apocalyptic grief—that was our modern truth. It was all there in the music.

In 2018, the Jewish Museum Vienna mounted an exhibit called “Leonard Bernstein: A New Yorker in Vienna.” The accompanying catalog featured the words “Bernstein in Vienna became the medium through which a prosperous democratic German-speaking cultural community could display its newly found post-war liberal tastes.” Yes, exactly. The ovations for Bernstein went on forever in part because Vienna was celebrating its release from infamy. Perhaps only an American Jew—open, friendly, but a representative of a conquering power—could have produced the effect that Bernstein did.

After his initial Vienna triumph in 1966, Bernstein returned to New York, and the embarrassment and condescending reviews petered out. Vienna had taught New York how to listen. The Europeans were enchanted by the expressive fluency that the New York critics had considered vulgar. Everyone but the prigs realized that Bernstein’s gestural bounty was both utterly sincere and very successful at getting what he wanted. He wasn’t out of control; he was asserting control. Karajan, by contrast, worked through the details in rehearsal and then, in performance, stood there with his eyes closed, beating time, thrusting out his aggressive chin and mastering the orchestra with his stick and his left hand. He was fascinating but almost frightening to watch.

Karajan radiated power when he conducted; Bernstein radiated love. Smiling, imploring, flirting, and commanding, he cued every section and almost every solo, and often subdivided the beat for greater articulation. If you were watching him, either in the hall or on television, he pulled you into the structural and dramatic logic of a piece. He was not only narrative in flight; he was an emotional guide to the perplexed. For all his egotism, there was something selfless in his work.

In 1988, when Bernstein and Karajan were both close to death, they had a final talk in Vienna. Karajan, after neglecting Mahler’s music for decades, had taken up the composer in his 60s and eventually produced two glorious recorded performances of the Ninth Symphony. The Austrian could no longer afford to ignore Mahler; he had become too central to concert life, to 20th-century consciousness, and Bernstein had helped produce that shift. They spoke of touring together with the Vienna Philharmonic. I am moved by the thought of the two old men, rivalries and differences forgotten, murmuring to each other in a hotel room and conspiring to make music. Mahler had brought them together.

A few days after struggling with the Vienna Philharmonic over Mahler’s Fifth in 1972, Bernstein performed and filmed the work with the orchestra in Vienna. The musicians are no longer holding back; it’s a very exciting performance (viewable on YouTube and streaming services). Fifteen years later, in 1987, Bernstein and the Vienna Philharmonic returned to the Fifth, taking it on tour. The performance in Frankfurt on September 8, 1987, was recorded live by Deutsche Grammophon and released the following year, and is also available to stream. It is widely considered the greatest recording of the symphony.

But it is not the greatest recording of the symphony. Two days later, on September 10, at the mammoth Royal Albert Hall in London, Bernstein and the orchestra played the work yet again. The BBC recorded the performance for radio broadcast, and though the recording (audio only) has never been commercially released, it has been posted on YouTube.

The symphony, in any performance, is a compound of despair, tenderness, and triumph. But in many performances, much of its detail can seem puzzling or pointless—vigorous or languorous notes spinning between the overwhelming climaxes. Bernstein clarifies and highlights everything, sometimes by slowing the music down so that one can hear and emotionally register such things as the utter forlornness of the funeral march in the first movement, the countermelodies in the strings that are close to heartbreak, the long silences and near silences in which the music struggles into being—struggles against the temptation of nothingness, which for Mahler was very real.

The symphony now makes complete sense as an argument about the unstable nature of life. Toward the end of it, after a passage slowing the music almost to a halt, Mahler marks an abrupt tempo change: accelerando. In Bernstein’s personal score, he writes at this point, “GO.” Just … go. In London, the concluding pages—with the entire orchestra hurtling in a frenzy to the close—release an ovation in the hall that has the same intensity of joy as the music itself.

Mahler’s music is the dramatized projection of a Middle European, Jewish-outsider sensibility into the world. Bernstein carried the thrice-homeless Mahler home, yes, home to the world, where he now lives forever. The conductor may have been frustrated in some of his ambitions (he was never the classical composer he wanted to be), but he blended in his soul what he knew of Jewish sacred texts, Jewish family life and family feeling—blended all of that with the ready forms of the Broadway musical, the classical symphonic tradition, Christian choral music. He took advantage of new ways of reaching audiences—particularly television—without cheapening anything he had to say. He died too young at 72, dissatisfied, full of ideas and projects, a man still being formed; yet throughout his half-century career, he brought the richness of American Jewish sensibility into the minds and emotions of millions of people.

This article was adapted from David Denby’s new book, Eminent Jews: Bernstein, Brooks, Friedan, Mailer. It appears in the May 2025 print edition with the headline “The American.”

By David Denby

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

Premium IPTV Experience with line4k

Experience the ultimate entertainment with our premium IPTV service. Watch your favorite channels, movies, and sports events in stunning 4K quality. Enjoy seamless streaming with zero buffering and access to over 10,000+ channels worldwide.