If not for the open casket, Ayn Rand’s funeral might have been confused for a party. On March 8, 1982, hundreds of admirers lined up outside a funeral home on Manhattan’s Upper East Side to pay their respects to the author and philosopher, basking in their shared love for the queen of selfishness. Inside, a phonograph played jovial turn-of-the-century tunes—Rand called it her “tiddlywink music”—at high volume. Colorful bouquets lined the room, including a six-foot-tall floral arrangement in the shape of a dollar sign.

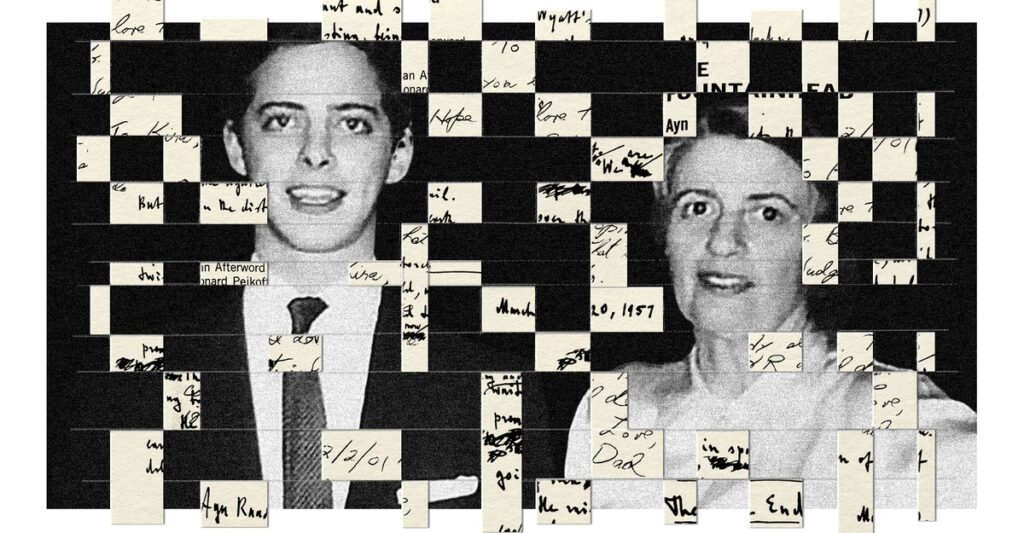

Off to the side, perched on a red plush couch, a man in his late 40s named Leonard Peikoff held court. Skinny and energetic, with groomed hair and thick glasses, he looked every bit the tweedy philosophy professor. He greeted well-wishers and answered questions about Rand’s remarkable life and singular philosophy. A visitor unfamiliar with Rand’s personal history might have assumed he was her son.

Peikoff’s devotion paid off: Rand designated him as her sole heir. He was not Rand’s original choice; she had promised her inheritance to other followers over the years. But by the time she died, she had alienated all of them. Peikoff was one of the only close friends Rand had left—the person she turned to for day-to-day help, for comfort, and for affirmation that she and her work still mattered.

Managing Rand’s estate would entail more than handling her personal property. By the end of her life, her philosophy of objectivism—which proclaims the glory of individualism and the evils of altruism—had become a full-blown movement, and it was now Peikoff’s job to guide it forward. Rand’s books sold in the millions, despite their imposing heft. Her angular face and enormous eyes were all over magazines and TV sets in the ’60s and ’70s, and her eccentric charm won over talk-show hosts like Johnny Carson and Phil Donahue. But Rand’s life had always been a mystery. She spoke little of her upbringing in Russia and kept her personal affairs private. The gap between her cultural ubiquity and the scarcity of information about her created a fascination bordering on obsession among both fans and detractors. The person in charge of her property—her diaries, her letters, the copyrights to her books—would wield great power over how Rand would be remembered.

The inheritance was also a windfall for Peikoff. Rand’s estate was worth an estimated half a million dollars at the time of her death, and her copyrights would eventually bring in hundreds of thousands of dollars a year in royalties. Peikoff, a lifelong advocate of autonomy and self-reliance, would never have to worry about money again.

After the funeral service, Peikoff asked to be left alone with the casket. Like Rand, he was a strident atheist; he knew she couldn’t hear him. Still, he spoke aloud to her, promising that he would live up to the responsibility she’d bestowed on him. He swore to keep her philosophy “pure,” and to make sure that her work lived on. “It was a vow,” he later said, “which I spent the rest of my life carrying out.”

Fulfilling that promise would come at a cost. His quest to defend Rand’s legacy would provoke nasty brawls with other objectivists. And his stewardship of her estate would lead to a painful conflict closer to home: Four decades after Rand’s death, Peikoff has found himself mired in an ugly legal battle with his own daughter. The dispute has left him estranged from friends and surrounded by courtiers, much like Rand at the end of her life. Peikoff’s Lear-like proclamations and denunciations have riveted the objectivist community. The chaos has risked damaging the legacy he swore to protect. And like many tragedies, this one is marked by a dark irony: A man devoted to the principle of individualism has ended up living a life defined by a reliance on others.

Leonard Peikoff was born in Winnipeg in 1933. His father, a Russian immigrant, was a surgeon whom Peikoff admired for his success but resented for his volatility and abusiveness; Peikoff would later compare him to a “dictator of the Soviet Union.” His mother was loving, but not intellectual in the way that Peikoff valued. He did well in school but struggled to make friends; the other kids called him “the brain.” When Peikoff was young, in a bizarre incident that made the local newspapers, he and his younger brother got swept out to sea in a rowboat and were not rescued until the next day. According to Peikoff, they spent the night talking about labor unions.

As a teenager, Peikoff agonized over what to do with his life. His father wanted him to become a doctor, but Peikoff had no interest in medicine; he wanted to study philosophy. Growing up meant choosing realism over idealism, his father always said. But Peikoff remained an idealist. Could he nonetheless find a way to make a living? The question tormented him.

Once a year, Peikoff’s father allowed him to travel to a U.S. destination of his choice. In 1951, during the spring of his freshman year at the University of Manitoba, he took the train to Los Angeles to visit his cousin Barbara Weidman. She had a connection to Ayn Rand through her boyfriend, Nathan Blumenthal—another child of Russian Jewish immigrants, who would later change his name to Nathaniel Branden—and Peikoff hoped to meet the author of his favorite book. The chance to ask his nagging question about idealism versus pragmatism was too good to pass up, and soon after his arrival Weidman and Blumenthal arranged a meeting.

Peikoff was nervous as their car approached Rand’s imposing ranch house in the San Fernando Valley, where she lived with her husband, Frank O’Connor. Once inside, Peikoff endured a minute or two of small talk before blurting out “Let’s get down to business” and asking his question: Can an idealist live pragmatically? Rand didn’t just take him seriously; she treated his question as the most urgent one in the world, fixing him with her black eyes and dissecting the dilemma with precise logic. Rand told him there was no contradiction between idealism and pragmatism—in fact, they were mutually supportive. As Peikoff later summarized it, “The more moral you are, the more successful you are.” Rand then brought up various counterarguments and shot those down too. Then she critiqued Peikoff’s method of thinking, explaining why he had not come up with the answer on his own. By the time she stopped talking, half an hour had passed.

Courtesy of Kira Peikoff

Peikoff first read The Fountainhead as a teenager. It was “like putting an electric plug into the wall,” he later said, after “waiting to be connected to some source of power.”

Peikoff left her house vibrating. Rand had given him something to live for: an entire worldview built on rationality and individual freedom. The world seemed good and full of possibility. His self-doubt was gone. Philosophy wasn’t just a way of thinking; it was a way of living. Peikoff knew that everything would be different from then on. That night, as he washed his hands, he thought to himself that he’d even have to find a new way to wash his hands now that he’d met Rand.

He returned to Winnipeg and spent two more years at the University of Manitoba. His father was still pushing for him to go into medicine, so before senior year, Peikoff made a deal with him: He would move to New York City, where Rand had relocated, and study philosophy at NYU for a year. Then he would come home to Winnipeg and become a doctor. “Of course, I never came home,” he later said.

In New York, his real studies began. By day, Peikoff would go to class. By night, he would visit Rand in her apartment. The gatherings of Rand’s growing inner circle, cheekily referred to by its members as the Collective, would become much mythologized. At the time, Rand was working on her novel Atlas Shrugged. Rand intended Atlas as a rollicking epic and the definitive statement of her philosophy, and expected it to be an even bigger triumph than The Fountainhead. At her Saturday-night gatherings, she would share the latest section, and the group—which included the now-married Barbara and Nathaniel Branden, as well as the young economist Alan Greenspan, whom Rand called “the Undertaker” for his dour mien—would offer feedback and discuss the philosophical points at hand.

Peikoff would also visit Rand alone once or twice a week to talk philosophy late into the night. As he described it in interviews years later, he would often leave her apartment as late as 4 a.m. and walk to the elevator, only for her to delay him to make a final point, yelling down the hall as Peikoff kept calling the elevator and sending it back. “I don’t know why the neighbors didn’t kill us,” he said in the 2004 documentary about his life. He’d then rush home to scribble it all down.

Week by week, Peikoff’s understanding of Rand’s philosophy grew. He would bring her questions about his lessons at school, and she would set him straight. Rand had little patience for modern philosophy, which she saw as a dunghill of subjectivity and moral relativism. According to Rand, the truth was knowable and could be discovered through reason, hence the name she gave her philosophy: objectivism. Rand also argued, famously, that people should act in their own self-interest and never make sacrifices for others, and that the system that best promotes individual flourishing is laissez-faire capitalism. Peikoff’s questions sometimes drove Rand nuts—she couldn’t understand why someone wouldn’t see things her way—but he endured her tantrums in exchange for wisdom. Peikoff said he learned “ten times more” during those bull sessions than from getting his Ph.D.

Peikoff had never had much success with women, and Rand offered to act as matchmaker. Reading through her mountains of fan mail, she and members of her circle kept an eye out for young women who might be a good fit. In 1955, they found a promising candidate: an aspiring actor and dancer named Daryn Kent. On their first date, Peikoff and Kent talked for hours about their shared admiration for Howard Roark, The Fountainhead’s protagonist. The two started dating and moved in together. (Kent also began working for Rand as a typist.) “I was in love with her,” Peikoff later said. According to Rand, love is inherently selfish: You love someone not as an act of altruism but because they share your values and make you feel good. If your morals are aligned, Rand argued, sexual attraction follows.

Still, the excitement of being part of the Collective during this creatively fertile period for Rand overrode other considerations for Peikoff. When Rand finally finished writing Atlas Shrugged in March 1957, the Collective celebrated it like an atheist Second Coming, popping champagne and staying up late. Peikoff predicted that the book would usher in a new era of political liberty and laissez-faire capitalism. Around that time, Peikoff would later recall, he and Rand were walking along Madison Avenue toward the office of her publisher when Rand turned to him and said: “Don’t ever give up what you want in life. The struggle is worth it.”

Rand and the Collective expected Atlas Shrugged to be hailed as a masterpiece. They were shocked when, upon its publication in October 1957, almost every major outlet panned it. (“I had to flog myself to read it,” the National Review founder William F. Buckley Jr. said.) Although the novel would become a perennial best seller and one of the most influential books of all time—second only to the Bible, according to one national poll—the critical reception felt like a blow. Rand sank into a depression, growing paranoid and intolerant of dissent, according to Heller’s biography. She expelled second-guessers from her circle. The Collective members who survived the purges became tighter than ever; in the early ’60s, many of them, including Peikoff, moved into the same high-rise on East 34th Street.

Even if Peikoff was Rand’s most devoted follower, he was not assumed to be her successor. That title belonged to Nathaniel Branden, whom Rand referred to as her “intellectual heir.” Rand made no secret of her favoritism, once describing the Collective “as a kind of comet, with Nathan as the star and the rest as his tail.” Starting in the late ’50s, with Rand’s blessing, Branden began teaching courses on objectivism under the banner of the Nathaniel Branden Institute, or NBI. (Rand didn’t want him to use her name, lest she have to answer for his errors.) Branden organized her ideas into a series of digestible lectures, giving her philosophy both structure and mainstream appeal.

What Peikoff did not realize—or did not want to realize—was that Rand and Branden were carrying on an affair. Starting in late 1954, with the permission of their spouses, the two began seeing each other romantically, despite the fact that Rand was 25 years older than Branden. The affair, as recounted in Branden’s memoir, was passionate and tempestuous, full of jealousy and psychological games. When Branden finally ended it, in 1968, Rand, who was then 63, responded with a barrage of verbal abuse and slaps in the face. She banished Branden from her circle and denounced him publicly, claiming that he’d betrayed the principles of objectivism, exploited her financially, and—perhaps worst of all—engaged in “irrational” behavior. She also cut Branden out of her will, telling Barbara that she was the new heir, until they, too, fell out soon after.

Courtesy of Kira Peikoff

Peikoff with his second wife, Cynthia, who once worked as Rand’s secretary.

In 1973, Peikoff failed to get tenure at the Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn and quit academia. Peikoff claimed his association with Rand had hurt his job prospects—“I was a pariah in the academic world,” he told an interviewer—and he didn’t excel at the “publish or perish” game. Peikoff’s commitment to Rand also strained his marriage. He and Ludel lived in the same building as Rand, and Peikoff continued his late-night discussions with his mentor. In 1978, he and Ludel divorced. Apparently there were no hard feelings: On Ludel’s recommendation, he started dating and soon married Cynthia Pastor, an aspiring psychologist who later became Rand’s secretary.

Toward the end of her life, Rand fell out with numerous friends—over book reviews, philosophical disagreements, perceived slights—and Peikoff took her side every time. The perpetual conflict was hard on Peikoff, according to Heller, who quotes an unnamed acquaintance saying, “Leonard was destroyed. He was a robot at the end.” When Rand’s scythe finally came for Blumenthal, Peikoff was left as her sole heir.

In November 1981, Peikoff and Cynthia accompanied Rand to what would be her last lecture, speaking to a group of businessmen in New Orleans. On the train ride home, Rand got sick, and she didn’t get better. She’d been a lifelong smoker and had already undergone lung surgery; she had also been diagnosed with arteriosclerosis, and her heart was failing. In her final weeks, Peikoff attended to her. One Saturday morning, he got a call from the nurse saying he should come quickly. “I ran like a maniac through the New York traffic,” he later recalled, “but by the time I got there she was dead.”

“It was just unreal to me,” Peikoff went on, describing Rand as “completely irreplaceable. Your mind just couldn’t get around it.” The Ominous Parallels, 12 years in the making, was finally published soon after Rand’s death. Rand had written the introduction, which concluded with a variation on a quote from Atlas Shrugged: “It’s so wonderful to see a great, new, crucial achievement which is not mine!”

With Rand’s death, Peikoff had lost the most important and controlling force in his life: a woman who demanded complete devotion, to the point of cutting off even his closest relationships. In time, he would find another.

Running Rand’s estate was a full-time job. Peikoff and Cynthia got to work sorting her letters and diaries, which would eventually be published as collections. Rand had wanted to donate her original manuscripts of The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged to the Library of Congress, but Peikoff kept the first and last pages of the former and hung them on his wall. (Federal agents later seized the pages after Peikoff said in an interview that he “stole” them; the seizure outraged Peikoff.) When she died, Rand had been working on a teleplay of Atlas Shrugged. Peikoff shopped around the rights for a film adaptation, a project that would take decades to materialize. And as Rand’s “intellectual heir”—a title that Rand had never officially bestowed upon him, according to Heller, but that he now claimed—Peikoff started working on what would become his definitive contribution to Rand’s legacy, a distillation of her thought titled Objectivism: The Philosophy of Ayn Rand.

In 1985, Peikoff, now living in Orange County, co-founded the Ayn Rand Institute, a nonprofit based in Marina del Rey, California. The goal, he wrote at the time, was to spread objectivism to a wider audience. The institute sponsored an annual essay contest for high schoolers with prizes in the thousands of dollars, and established an archive for Rand’s papers.

With Rand no longer around to defend herself from critics, Peikoff redoubled his efforts to protect her. In 1989, he excommunicated a prominent objectivist named David Kelley—he’d read a Kipling poem at Rand’s burial ceremony—for the sin of speaking to a group of libertarians. (Despite Rand’s reputation, she was opposed to the libertarians of her time, dismissing them as anti-intellectual anarchists.) Kelley wrote an essay arguing that objectivism “is not a closed system,” and that its followers needed to engage with other ideologies in order for it to grow and spread. Peikoff wrote a high-handed response declaring that objectivism was in fact “closed.” Kelley went on to start a competing, comparatively inclusive objectivist organization now called the Atlas Society.

“He was an amazing father,” Kira, who is now 39 and lives in New Jersey, told me. Many summers while she was growing up, he took her to Hawaii. After he and Cynthia got divorced, when Kira was 6, Peikoff signed up for a group for divorced fathers and daughters to help them bond. The two would sometimes play a game in which they told collaborative stories, alternating sentences to spin a yarn. He tried to avoid indoctrinating her with his ideology, Kira recalls, but he did hire an objectivist teacher to homeschool Kira and a couple of other students for three years during middle school, with lessons free of multiculturalism or moral relativism.

When Kira was young, Peikoff told her that she would inherit part of Rand’s estate after he died. He eventually decided that Kira would get the copyrights to Rand’s three biggest books—Atlas Shrugged, The Fountainhead, and We the Living—and that the rest of Rand’s works would go to the Ayn Rand Institute. Peikoff gave Kira a copy of The Fountainhead with an inscription alluding to Howard Roark’s uncompromising independence: “Judge it completely on your own, ignoring your parents’ opinions & everybody else’s. That’s what HR would do.”

Kira finally read Atlas Shrugged in college. Studying journalism at NYU, she skipped classes and stayed up late to tear through the novel. “I was so utterly gripped by the book,” she told me. “I remember crying at the end of it and thinking, Now I get it. This is going to be my life philosophy as well.” When she met the man who would become her husband, they bonded over their love of Rand’s books, which inspired him to scrap a career in finance and pursue his passion for music.

After college, Kira decided to try to write novels, a pursuit that brought her even closer to her father. Peikoff encouraged her and agreed to sponsor her for one year. When Kira got her first book deal, in 2010, Peikoff proudly blogged about it. After years of playing their storytelling game, he was happy to take some small credit for her success. Kira soon had kids of her own, and Peikoff delighted in playing with them, marveling at their smarts and athleticism.

Even as Peikoff thrived as a father and grandfather, however, his professional life was becoming more controversial. Although he had resigned from his position as chair of the ARI board in 1989, he retained influence over the institute’s policies. After the Kelley schism, throughout the ’90s and 2000s, he continued to issue fiats and purge deviants. The number of pariahs climbed: the economist George Reisman, for questioning some of Peikoff’s decisions at ARI; the Atlas Shrugged film producer John Aglialoro, for participating in an event with the libertarian Cato Institute; the historian and philosopher John P. McCaskey, for daring to criticize a Peikoff-endorsed book about methods of scientific discovery. In a public letter denouncing McCaskey, Peikoff called him “an obnoxious braggart as a person, and a pretentious ignoramus as an intellectual.”

As with Rand, the irony of someone ostensibly dedicated to freedom of thought demanding ideological conformity was inescapable. Some wondered whether Peikoff, who’d had a heart attack in 1991, had lost a step. In response to the 2010 McCaskey flap, Peikoff’s cousin Barbara Branden—who hadn’t spoken with him in decades—commented on an online forum: “As we grow older, we become more firmly and openly the person we really are. Leonard Peikoff is not senile. He is merely Leonard Peikoff.” (Barbara Branden died in 2013.)

Peikoff also drew criticism for his management of the estate. In the ’90s, as ARI allowed scholars to examine Rand’s letters and diaries, some of them noticed discrepancies between the published documents and the originals. One Rand scholar revealed in a 1998 article that the editors of her published journals had apparently cleaned up her prose, omitting context at best, changing the meaning of sentences at worst. Whether or not Peikoff had directed the changes, the airbrushing occurred under his watch, damaging the credibility of both ARI and the movement—not to mention their commitment to the value of objectivity. Over the years, some scholars perceived as insufficiently aligned with Rand or ARI have been restricted or denied access to the archives. (ARI did not respond to my requests for access or for comment.)

Peikoff seemed to accept that he would be remembered as Rand’s propagandist. “If I am to go down in history as her apologist or glamorizer, then so be it,” he said in one lecture. “I am proud to be cursed as a ‘cultist,’ if the ‘cult’ is unbreached dedication to the mind and to its most illustrious exponents.” In 2011, when someone asked who would be his intellectual heir, he said, “Nobody I know qualifies.” It surely didn’t help that his world was shrinking—and would soon shrink further.

In early 2020, Peikoff, then 86, was lonely and miserable. He was living at the Ivy at Wellington, a retirement home in Orange County, and wasn’t allowed to leave due to pandemic restrictions. A woman he’d been in love with at the home had died the year before, at age 99, a loss that he described as “a tragedy” in one of his diary recordings. And with a media diet of talk radio and the New York Post, not to mention a lifetime of anti-regulatory messaging under Rand, Peikoff bristled at the lockdowns and mask mandates. Kira and her family were living nearby temporarily; often, she would stand outside Peikoff’s residence so they could see each other while talking by phone.

That spring, Peikoff’s friend Carl Barney visited him at the Wellington and was horrified at Peikoff’s state. “He was alone, clearly despairing, using oxygen with a tank,” Barney wrote on his blog. “I feared for his life.” He decided to hire a nurse to take care of his friend. After some research, Barney found an agency called Golden Age Companions and hired a woman named Grace Davis.

Davis, then in her 50s, was quiet and professional at first, according to Kira and Peikoff’s former driver. She and Peikoff clearly got along well, despite the fact that he was an avid atheist and she was a churchgoing Christian. But people near Peikoff soon started to notice her behaving in inappropriate ways. On his birthday that October, she gave him an affectionate card: “I hope you know I love you in an agape & phileo way,” she wrote, using the Greek words for unconditional and brotherly love. She would call Peikoff before he went to sleep, and join him to watch the Viennese operettas that he and Rand had always loved, according to Kira. Within a year or so of Davis’s arrival, a friend of Peikoff’s saw him and Davis exchange kisses, as that friend later testified in a deposition. (Through his lawyer, Peikoff declined an interview request and did not answer a list of questions about this story, which he said consisted of “baseless and false charges.”)

Kira grew concerned about Davis in January 2021, after Peikoff had a life-threatening case of COVID. When he was released from the hospital, Kira, on the recommendation of Peikoff’s doctors, asked Davis to take a COVID test, because Peikoff was in a vulnerable state. Davis provided a document that supposedly confirmed her status as negative, but it was an undated, unaddressed letter apparently printed on County of San Diego Health and Human Services Agency letterhead. Suspicious, Kira contacted the testing company to ask for a sample test result and was shown a very different-looking document. Kira’s husband, Matt, confronted Davis about the document over text, but Davis never responded; according to Kira, her father later acknowledged that Davis’s letter was fake. (When I contacted the health agency, a spokesperson would not say whether the letter was authentic or not.)

According to Kira, when she confronted Peikoff about the apparent deception and demanded that he get rid of his nurse, Peikoff threatened to kill himself if Davis left. Kira didn’t trust Davis to manage Peikoff’s medical care, so she tried to cut Davis off from Peikoff’s doctors, saying they should instead communicate with Peikoff’s assistant; she also hired another nurse to provide supplemental help for a short period. But Kira soon moved back to New Jersey and was limited in what she could do from afar.

In January 2022, Peikoff wrote Kira a heartfelt letter. In it, he thanked Kira “for loving me and showing it. You know my doubts about being loved. But yours is what I have no doubt about.” (“He’s always been very insecure about whether people truly love him for him, or whether it’s because of his status in objectivism,” Kira told me.) He soon amended his will to include not just Kira but also her husband and kids as beneficiaries of his literary trust.

Any peace of mind that gesture might have brought Kira was spoiled in early 2023, when Peikoff helped Davis and her adult son, Jaymeson—an EMT who was helping care for Peikoff—buy a house in an expensive neighborhood near San Diego. They wanted to turn the house into a “board and care” facility for the elderly, including some of Peikoff’s friends from the Wellington, he told her. Peikoff initially told Kira he would contribute $200,000; the promised amount soon went up to $2 million, according to a sworn declaration by Kira. But the house they settled on—a $3.7 million mansion in Rancho Santa Fe—had only five bedrooms, which wouldn’t accommodate many residents beyond Peikoff, Davis, and Jaymeson. After purchasing the house, Peikoff signed a document transferring ownership to Davis. According to Peikoff’s former dog-walker and driver, he asked them to keep the transaction a secret. Worried that he was being exploited, one of them decided to tell Kira anyway.

“I freaked out,” Kira told me. “I was like, What are you thinking? What are you doing? This is your caregiver. And why are you doing this behind everyone’s back?” Kira begged for help from Peikoff’s lawyer and his psychiatrist. She noted that California law treats large gifts from a dependent elder to a caregiver as “presumed to be the product of fraud or undue influence.” But the transaction was done. (In public court documents from 2005 related to Davis’s divorce, her ex-husband claimed that Davis had several aliases and Social Security numbers, accused her of credit-card fraud, and alleged that she’d used his credit history to fraudulently apply for a bank loan. Davis did not respond to multiple interview requests for this article. Her lawyer declined to address specific questions, but described the allegations against Davis as “highly inflammatory, malicious, and false.”)

A month later, Peikoff wrote to Kira apologizing for his “emotionalist” behavior (the worst kind for an objectivist) and promising her “the totality of the Estate” when he dies. To assuage her concerns, he transferred $2 million of his stock portfolio to Kira as an upfront payment on the inheritance. “I hope this letter enables us to go on being two people who unconditionally love each other,” he wrote. But Kira still had concerns about Davis. Although she hadn’t seen any romantic behavior between Peikoff and his nurse, she knew they were getting close; a few weeks later, Kira told Peikoff that she was worried he was going to marry Davis and that she would take everything. According to Kira, he laughed off her concerns.

In the summer of 2023, Peikoff was hospitalized for sepsis and pneumonia. Doctors put his chance of recovery at 50–50, according to Kira, who says that Peikoff was never the same afterward. When he got out and moved into the new house in Rancho Santa Fe, Kira struggled to reach him despite numerous calls and texts to him and Davis. According to Kira, Davis told her they were going to install a landline, but they never did. A night nurse who was working for Peikoff at the time said in a sworn statement that Davis and Jaymeson would turn off the ringer on Peikoff’s phone so he wouldn’t hear it, and would screen his emails. (Jaymeson declined to be interviewed for this article and did not respond to requests for comment.) At one point, an email from Kira was mysteriously deleted from Peikoff’s inbox, according to his assistant at the time. In her statement, the night nurse also described Peikoff as completely dependent on Davis: “Grace would make decisions on Leonard’s behalf or tell him what to do and Leonard would simply agree.”

Nine days after his discharge from the hospital, Peikoff told Kira that he did, in fact, now want to marry Davis. “He said, ‘I want to have a family around me, not paid help,’” Kira recalled. “At that point, I was in a total panic. I didn’t believe she was in it for the love of a 90-year-old, very disabled, ill man.” In her recollection, Peikoff told her they would get married in November and go to Fiji together. But then, in September, he called Kira with some news: He and Davis had gone to the San Diego courthouse and were now husband and wife. Kira, trying to stay calm, told him he needed to amend his will to make sure that she would still receive the portion of the estate he’d promised her. He assured her he would. He also said there would be a wedding celebration a few months later, according to Kira. But then he and Davis abruptly moved up the date—all while Kira was trying and failing to get her father to sign a document that would guarantee her the copyrights to the three novels—and held a ceremony in their backyard. Kira and her family did not attend. In one photo taken that day, Peikoff sits in a wheelchair, holding Davis’s hand. In her sworn statement, Peikoff’s night nurse at the time said that Peikoff was disoriented and “did not understand he was getting married.”

The next month, Kira flew out for Peikoff’s 90th birthday. The day she arrived, Peikoff told her in an email that though she would still inherit the copyrights to Rand’s three biggest books, he would divide his assets between her and Grace in a 50–50 split. “I have now married a wife whom I love, and I intend to be sure that she is looked after financially,” he wrote. The next day, Kira pulled him into a private room and told him that she thought Davis was taking advantage of him. Peikoff said he understood her point of view, and in order to preserve their relationship, they eventually agreed not to discuss Davis anymore. But a few months later, Peikoff’s night nurse told Kira that she had witnessed Davis and Jaymeson mistreating Peikoff—screening his calls, pressuring him to change his will, and failing to administer proper treatment on a day when his blood pressure spiked to a dangerous level—and Kira raised the matter with her father. After a tense back-and-forth, Peikoff said he was removing Kira from his will. When Kira later called him in a last-ditch effort to make amends, he responded coldly. “You’re my enemy,” he said, according to Kira. Once again, he had cut off someone close to him out of devotion to the woman at the center of his life.

In March 2024, Kira played her final card: She filed a petition in San Diego Superior Court to put a conservator in charge of Peikoff’s trust. The petition claims that Davis exercised “undue influence” over Peikoff by isolating him, persuading him to buy the Rancho Santa Fe house, marrying him, neglecting his medical needs, and “poisoning” his relationship with Kira. As a result, Kira argued, Peikoff could not be trusted to make his own financial decisions.

Peikoff’s legal response might be the most objectivist objection ever filed. It opens with a quote from Ayn Rand: “My philosophy, in essence, is the concept of man as a heroic being, with his own happiness as the moral purpose of his life, with productive achievement as his noblest activity, and reason as his only absolute.” And it includes Peikoff’s own declaration of independence: “If being reasonable is sitting in a library, alone, until I die, and if being unreasonable is choosing to be with the woman I love, then I choose to be unreasonable.” That choice, Peikoff’s lawyer argues, was made purposely and with “abundant and overwhelming mental capacity,” an assertion supported by statements from doctors. He claims that Kira “has omitted very significant facts from her pleadings, and also included outright lies,” and that her communication with Peikoff in recent months amounted to “harassment,” concluding, “Leonard Peikoff should remain a free man.”

In September, an open letter with Peikoff’s byline appeared on an objectivist website. In it, Peikoff went even further, saying that he no longer loved Kira and that she was motivated by “Greed, Jealousy, and Revenge.” He framed the conservatorship as an objectivist’s worst nightmare: submitting oneself to the government. If implemented, it would “enslave me immediately.” He then called on all objectivists to help him fight. Because he had already given Kira “a sizable fraction” of his estate, he wrote, he didn’t have enough money to pay his legal expenses. The letter included a link to a GoFundMe page requesting $40,000 in donations, organized by an objectivist friend named James Valliant. It raised $28,000.

The conservatorship petition and Peikoff’s explosive reaction captivated the objectivist community. Prominent members took sides online. Some saw a daughter desperate to protect her vulnerable father in his final years. Others saw a man in love, trying to live out the rest of his life according to his own wishes—and a daughter attempting to control him.

As in schisms past, those who didn’t side with Peikoff found themselves cut off. Kira, now deluged with inquiries from friends and admirers of her father, posted a message on Facebook requesting privacy, along with a photo of herself and Peikoff taken a year before, at his 90th birthday, the last time she had seen him. “I deeply miss my father, the man who unconditionally loved me for 38 years,” she wrote. “I dream of him often, and it’s always the way he used to be—the loving, steadfast, and kind father I knew, not the man who has now become unrecognizable.”

Courtesy of Kira Peikoff

Peikoff and Kira at his 90th birthday party, in October 2023

Valliant, a lawyer who once wrote a book meticulously rebutting claims made in the Brandens’ memoirs—it was titled The Passion of Ayn Rand’s Critics—took the lead as Peikoff’s spokesperson and defender in chief. In September and October, he posted on YouTube two long video interviews with Peikoff in which they discuss politics, Peikoff’s love for Davis (she makes a brief appearance), and his future plans for the estate (he says he is appointing a committee of objectivists to handle it). In the videos, Peikoff slurs his words and breathes through an oxygen tube but speaks lucidly and energetically. The subtext: Peikoff is still with it. (Valliant declined an interview request, saying he could not speak with me because of possible “further litigation.”)

Andrew Lewis, a longtime friend and former colleague of Peikoff’s, told me that the claim that Davis has isolated him is “garbage.” Lewis said he sees Peikoff every Sunday, and that a few dozen people showed up to celebrate his 91st birthday in October. Some old friends even flew in. It’s just the people who have taken Kira’s side that he doesn’t want to see, Lewis said. He also dismissed the idea that Davis is manipulating Peikoff as “bullshit.” I asked why. “Because he loves her,” Lewis said. “And she cares for him. And as far as I can tell, she loves him back.”

Kira rescinded her conservatorship petition in November. She’d received an anonymous threatening message on X—“i can be anywhere at anytime,” the person wrote, adding that Kira and her husband “don’t really understand force qua force”—and didn’t want to make her father spend his twilight years in court. “My father’s love for me has been destroyed, and I no longer believe that any amount of evidence brought to his attention will open his eyes,” she told me. However, when I asked whether she planned to sue after Peikoff’s death, she didn’t rule it out. Aside from her own financial interest, she said, she worries about what will happen if Rand’s estate is controlled by someone with no background in objectivism and no experience in philosophy or publishing.

But she also told me she understands why her father has chosen Davis. “I think my dad is someone who is desperate for affection,” Kira said. “And I think she provides that.” He’s always been gullible and generous, she added, and the combination makes him easy to manipulate.

From that perspective, perhaps Peikoff is living the Randian dream. As he sees it, he’s doing what he wants, acting in his own perceived self-interest to the very end. Sure, it’s hard to square the ideals of individualism and autonomy with an adult life characterized at nearly every turn by dependence: first on Rand’s approval, then on her largesse, and now on Davis.

But he doesn’t seem to mind. In his interview with Valliant, Peikoff—wearing a Hawaiian shirt, oxygen tubes in his nose—glows as he describes his first encounter with Davis: “I saw a woman coming toward me, and I thought to myself, A nurse can’t possibly look like that. Wow! That beautiful hair, framing her face, cascading down; beautiful figure; such gorgeous features. And her smile transported me to another world. So I fell for her right away.” He was even more delighted to discover she liked the things he liked, such as Viennese operetta and Wordle. “Not only is she beautiful,” he says, “she has my soul.” He gushes about the workout routine she designed for him, brags about how he convinced her to marry him after proposing four times, and says he wrote a 14-part essay about all the reasons he loves her. When she appears on-screen, smiling toward the camera, he kisses her. “This is my beautiful wife,” he says. And then he grasps her hands, fumbling a bit, and reaches for her arm, only for her to pull it away.

*Lead image credit: Illustration by Akshita Chandra / The Atlantic. Sources: ZUMA Press / Alamy; Kira Peikoff

Premium IPTV Experience with line4k

Experience the ultimate entertainment with our premium IPTV service. Watch your favorite channels, movies, and sports events in stunning 4K quality. Enjoy seamless streaming with zero buffering and access to over 10,000+ channels worldwide.