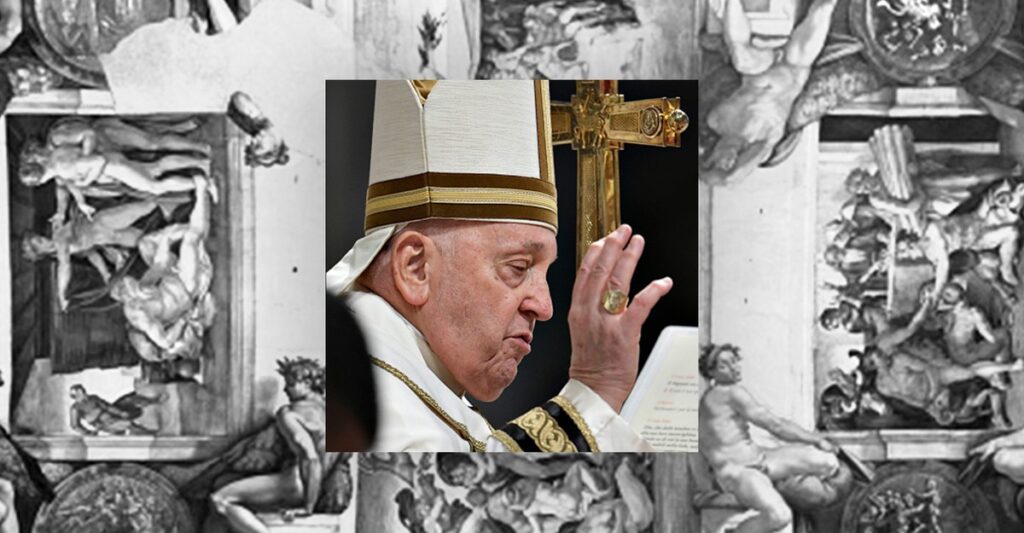

In a letter to America’s bishops, Pope Francis last month decried a “major crisis” unfolding in the United States: “the initiation of a program of mass deportations.” He called on “all the faithful of the Catholic Church, and all men and women of good will, not to give in to narratives that discriminate against and cause unnecessary suffering to our migrant and refugee brothers and sisters.”

Border-hawk Catholics were scandalized.

R. R. Reno, the editor of the traditionalist religious magazine First Things, denounced the pope as “an accelerationist” who believes that a “borderless fraternity is a true utopia.” The Daily Wire’s Matt Walsh characterized the letter as “pure nonsense,” while the Heritage Foundation’s head, Kevin Roberts, called it a “veiled shot” at Catholic supporters of Donald Trump. Tom Homan, President Trump’s border czar, addressed Francis directly: “I got harsh words for the pope … He ought to fix the Catholic Church and concentrate on his work, and leave border enforcement to us.” (Each of these critiques came before Francis’s hospitalization last month.)

Throughout Francis’s papacy, some American Catholics have accused him of prioritizing a platitudinal liberalism over doctrinal orthodoxy. But on the issue of immigration, Francis’s critics are the ones who appear to be sidestepping Catholic tradition—even while claiming to uphold it.

Start with the incident that prompted the current intra-Catholic dispute over immigration: a back-and-forth between the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops and America’s highest-profile Catholic official. After the Trump administration authorized Immigration and Customs Enforcement to apprehend people in churches and other social-service ministries, the USCCB called the move “contrary to the common good.” Vice President J. D. Vance came to the administration’s defense.

“There’s this old-school—and I think it’s a very Christian concept, by the way,” Vance told Fox News’s Sean Hannity in late January, “that you love your family, and then you love your neighbor, and then you love your community, and then you love your fellow citizens in your own country, and then after that you can focus and prioritize the rest of the world.” Vance’s rationale sparked intense debate in Catholic circles, especially online: His supporters cheered his use of religious rhetoric, while his detractors accused him of ignoring key parts of the Gospel.

Christian theologians through the ages have indeed articulated versions of this principle—called ordo amoris, or “the order of love”—including Church fathers such as Saint Augustine in the fourth century (“Since you cannot do good to all, you are to pay special regard to those who, by the accidents of time, or place, or circumstance, are brought into closer connection with you”) and Saint Thomas Aquinas in the 13th (“We ought to love more specially those who are united to us by ties of blood”). True Christian love, the principle suggests, is guided not by an impulse to maximize utility but by a compassionate preference toward the personal and proximate.

Many of those same Catholic theologians, however, believed that this preference is conditional, not absolute. As Aquinas himself wrote in the Summa Theologiae: “In certain cases one ought, for instance, to succor a stranger, in extreme necessity, rather than one’s own father, if he is not in such urgent need.” Rightly ordered love prioritizes close kinship—all things being equal. But it’s not ignorant of context or necessity.

Based on the outcry that followed Francis’s letter, you’d be forgiven for thinking it marked a dramatic departure from the views of his predecessors. It didn’t. “To welcome” the undocumented migrant “and to show him solidarity is a duty of hospitality and fidelity to Christian identity itself,” Pope John Paul II said in 1995. His successor, Pope Benedict XVI, remarked that immigrants and native-born people alike “have the same right to enjoy the goods of the earth whose destination is universal, as the social doctrine of the Church teaches.” In 2010, he selected “one human family” as the theme for the World Day of Migrants and Refugees.

To be sure, none of the three most recent pontiffs argued that immigration is an unbounded good. Benedict XVI granted that nations are entitled to “regulate migration flows,” while John Paul II thought that “illegal immigration should be prevented.” Francis himself noted in his letter “the right of a nation to defend itself and keep communities safe” from violent criminals, and he stressed the need for “policy that regulates orderly and legal migration.”

Still, some of Francis’s critics interpreted the letter as a declaration that countries should admit every migrant who doesn’t have a criminal record. They typically cited this line: “The rightly formed conscience” should not equate the “illegal status of some migrants with criminality.” But Francis has previously acknowledged that stricter enforcement can be necessary. In a 60 Minutes interview last year, the pope said that a migrant should be received initially but, in certain situations, “maybe you have to send him back.”

Some might reasonably find all of this to be another instance of Francis’s imprecision—as a Catholic myself, I understand their frustration—or think it imprudent for him to intervene in such a contested and complicated political matter. True enough, his letter wasn’t primarily concerned with balancing competing interests; his goal, it seems, was to emphasize what he regards as the moral error that underlies much of the immigration debate in the United States. If in doing so the pope is guilty of eschewing some nuance, his critics seem altogether uninterested in the deficiency he was pointing out.

They wouldn’t have to look very far. The first Trump administration enforced a brutal policy that separated thousands of parents from their children, as my colleague Caitlin Dickerson reported. (In October, a journalist asked Homan whether there’s a way to carry out mass deportations without separating families; he replied, “Sure there is: Families can be deported together.”) In many cases, restrictionist sentiment has given way to outright xenophobia, perhaps most memorably during Trump’s 2024 campaign, when he scapegoated Haitian migrants in Springfield, Ohio. (Matt Walsh contributed to the panic in a video titled “Third World Immigrants Are Ruining Our Towns and Eating Our Pets.”) And as the second Trump administration froze funds for initiatives such as the USCCB’s refugee-resettlement program, the bishops’ conference laid off 50 workers last month. (Responding to pushback from the USCCB over the administration’s loosened ICE guidelines, Vance suggested that the bishops are more “worried about their bottom line” than about caring for migrants.)

While the White House posts deportation ASMR videos and ICE ramps up raids that sometimes mistakenly detain citizens, it’s hard to read Francis’s letter as gratuitous pining for a borderless utopia. Rather, the pope seems to be making a plea for rhetoric and policies that respect the dignity of every human life—a long-standing Catholic concern that U.S. immigration-policy debates so often ignore.

Premium IPTV Experience with line4k

Experience the ultimate entertainment with our premium IPTV service. Watch your favorite channels, movies, and sports events in stunning 4K quality. Enjoy seamless streaming with zero buffering and access to over 10,000+ channels worldwide.