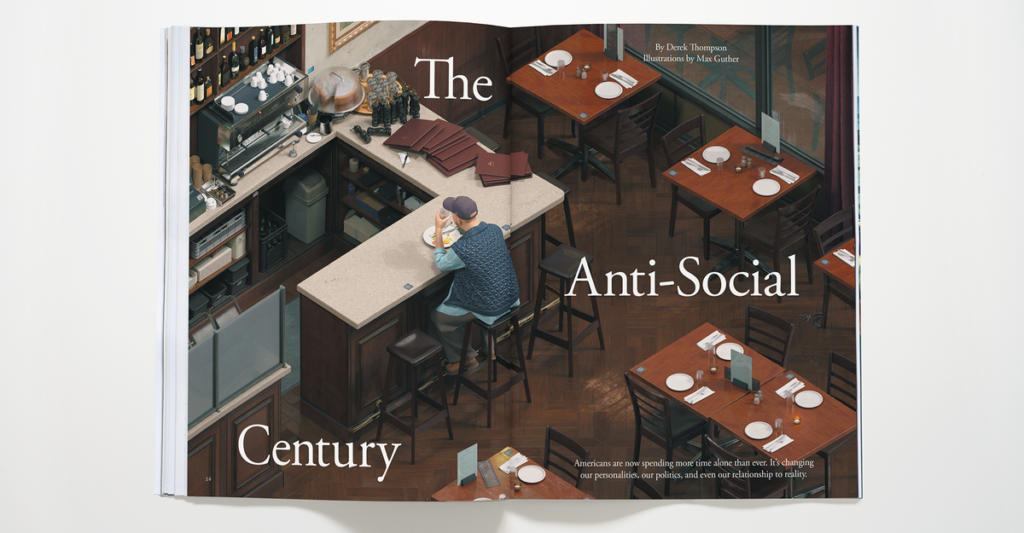

The Anti-Social Century

Derek Thompson’s article resonated with me deeply, but I think he missed one key reason people stay at home: financial necessity. As a 28-year-old raised on TV, I often succumb to the urge to binge my favorite shows at home because it feels more comfortable than going out. And as an early-career social worker with a small salary and little disposable income, staying home also feels more responsible. With the cost of everything—dinner, drinks, concert tickets—on the rise, I have to pick and choose where to spend my money outside the house. Even hosting a gathering and providing snacks can be costly. Especially during the cold winter months, it’s challenging to find cheap things to do with other people.

How should municipalities counter the anti-social century? I think offering free spaces and activities for the public would be a good place to start. And maybe I’ll start talking with strangers on the train.

Alexandra Lubbe

St. Louis, Mo.

As a Boomer who came of age in the ’60s, I recall how my hometown, Nashville, closed public swimming pools to avoid giving minorities equal access. No doubt, the erosion of a broader social cohesion began as taxpayers willingly—and sometimes enthusiastically—supported the demise of the vital infrastructure that Derek Thompson highlights.

Mark Forrester

Elkton, Md.

“The Anti-Social Century” is a much-needed update on our national alienation from one another. I’ve always thought that the foundational work on this subject was Philip Slater’s The Pursuit of Loneliness: American Culture at the Breaking Point, published in 1970. I read it a few years after it came out, as a college student, and I felt that no book did more to explain the cultural and economic forces that lead to our individual isolation. Slater would be appalled but perhaps not surprised to see how the trends he identified in the previous century have escalated in this one. Among other things, he noted that our obsessive devotion to rugged individualism separates us not only from one another, but from nature itself. “We feel that nature has no business claiming a connection with us,” he wrote, “and perhaps one day we will prove ourselves correct.” Some 50 years later, we seem to be well on our way to fulfilling Slater’s dark prophecy.

Scott Sparling

Lake Oswego, Ore.

After I retired from a career that involved regular human interaction, my wife noticed that I wasn’t experiencing the relaxation usually associated with retirement; instead, I was unsettled. She suggested that I try driving for Uber, and it’s made a huge difference in my life. Driving has become my personal answer to isolation, and it’s a hobby I intend to pursue as long as practical.

I’m amazed by how many people of all backgrounds enjoy engaging with a stranger. As I drive, we share small slices of our lives and usually part with an elevated sense of contentment. The notable exceptions to this rule are high-school-age kids, who I’ve noticed struggle to have easy conversations. It’s sad because, although we share a city, we have little insight into one another’s daily reality, into how our lives intersect outside the Uber experience. I sense that there is a lot to learn and understand.

Harry David Snook

Madison, Wis.

I live in western North Carolina, in an area devastated by Hurricane Helene. A few miles down the road, the Swannanoa River rose so quickly that people I knew had to swim out of their windows to survive.

I’m not as plugged in as most people. But when the storm hit and the phone towers went down, I finally met my neighbors for the first time since I moved to my street two years ago. Without technology, everyone went outside. In that new landscape, we cared for one another, and I need you to know how beautiful that was: When emergency radio broadcasts replaced our phones, we learned our neighbors’ names.

I don’t mean to diminish the lives lost or the landscapes irrevocably altered, but it’s hard not to mourn that post-flood camaraderie now that everyone has shut themselves away again. Helene brought about a different world. Perhaps calamities have the power to momentarily suspend the sickness of American modernity that Derek Thompson so aptly describes. It did for us, if only briefly.

McKinnon Brenholz

Black Mountain, N.C.

I am 27, and I fall on the cusp of Gen Z and Millennial, not quite fitting into either generational category. I spent my childhood playing outside and on the internet. When I was a teenager, social media was just beginning to become popular. I was shy in school and found myself becoming isolated in the 2010s, retreating into online spaces to find friendship. I stayed lonely and online until adulthood, when a sudden interest in and love of hiking propelled me outside and into the “real world.” Since then, I have joined a religious community and become dear friends with my neighbors; I strike up conversations with strangers on planes and in public. My life could not be more different, and when I reflect on the time I spent alone and online, I think of how wonderful my life could have been if I had dared to move outside my comfort zone sooner.

When I speak with friends my age, so many of them acknowledge that we are better off cultivating relationships offline—and yet we all still spend so much time online. My hope is that community organizing and free public spaces will become more common as we all look around and realize that none of us is happy with the status quo.

Christina Tavella

Boston, Mass.

Derek Thompson replies:

I think the most important point of my article is exactly what Christina Tavella notes in closing. The anti-social century is, among other things, a story of the vast gulf between our stated and revealed preferences—the lives we say we want and the lives we lead. Very few people will tell you that the way they wish to spend the scarce hours and days of their lives is to be more alone with each passing year, or to spend more time with their screens and less time with their friends and families. The fact that we choose aloneness over and over again suggests that aloneness is serving us, in some way. But I strongly believe that it is serving our shallow desire for convenience rather than our deeper need for connection and meaning. We have built a culture organized around the frictionless acquisition of dopamine. Are we sure we’re meant to do that?

Behind the Cover

In this month’s cover story, “Growing Up Murdoch,” McKay Coppins reports on the bitter fight within the Murdoch family to control its media empire. For our cover image, we selected a 1987 photograph of the Murdochs. Rupert Murdoch and Anna, his second wife, pose with 16-year-old Lachlan (left ) and 14-year-old James (right ) at an event at Sotheby’s in New York City. Today the brothers are on opposite sides of a legal battle to determine the future of the family business—and conservative media.

— Lucy Murray Willis, Photo Editor

Corrections

“ ‘I Am Still Mad to Write’ ” (March) originally stated that, after an accident in Rome, Hanif Kureishi came to consciousness a paraplegic. In fact, he came to consciousness a tetraplegic. “Why the COVID Deniers Won” (March) misstated the U.S.’s gross public debt in 2017 and early 2025. The debt was about $20 trillion in January 2017 and more than $36 trillion in early 2025, not about $20 billion and nearly $36 billion, respectively.

This article appears in the April 2025 print edition with the headline “The Commons.”

Premium IPTV Experience with line4k

Experience the ultimate entertainment with our premium IPTV service. Watch your favorite channels, movies, and sports events in stunning 4K quality. Enjoy seamless streaming with zero buffering and access to over 10,000+ channels worldwide.