Sometimes, riding my bike around Oakland, California, on a cold morning—bumping over abandoned railroad tracks, through the shadows of new towers, under leafy trees, past the encampments—I try to imagine all the money flowing in and through the place. In high-school physics, we had to sketch diagrams that laid out all the different forces acting on an object. What if I could do the same, but for the economic pressures on a place?

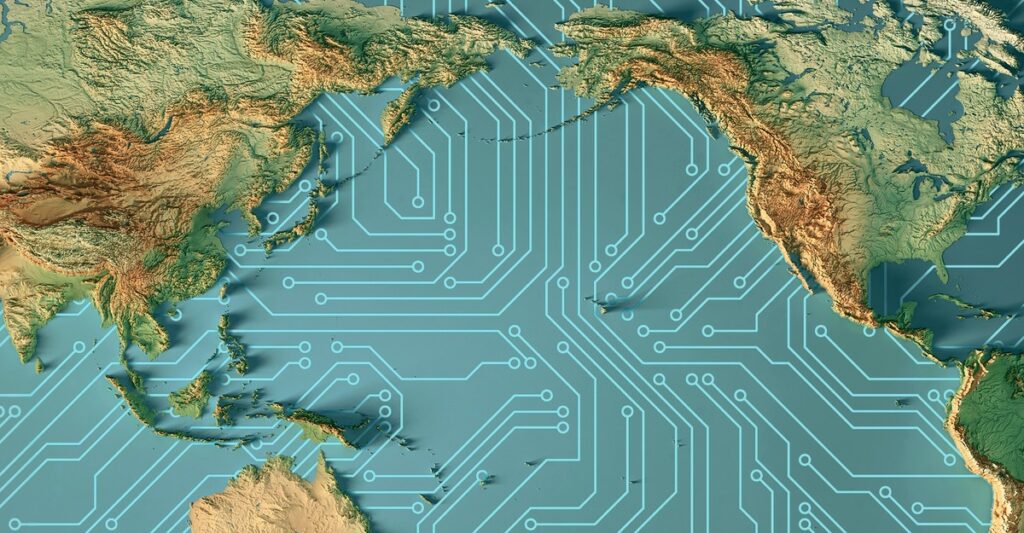

The Bay Area sits between the manufacturing economies of Asia and the consumer economy of the United States. In recent decades, it has been profoundly reshaped by the system of trans-Pacific trade, in which American corporations import manufactured goods from Asia through port cities strung along the West Coast, from Seattle to Long Beach. It’s a system I call the “Pacific Circuit,” and I’ve spent the past nine years trying to understand it.

For technology companies and their executives, this system has proved incredibly lucrative. For the communities like Oakland through which the goods travel—designated by mid-century urban planners as environmental-sacrifice zones—the story has been very different. Sketch a force diagram for Oakland, and you’ll see large vectors representing the technology industry and the containerization of cargo tugging at the city, pulling it apart.

Look around Silicon Valley today, at the gleaming buildings filled with white-collar workers sitting at their desks, and it can be hard to remember that electronics is actually a manufacturing industry. Few people today see Silicon Valley as a postindustrial landscape, but it once held so many factories that it had more Superfund cleanup sites than anywhere else in America. Only some of the production occurred in the valley itself; the electronics industry also pioneered the outsourcing of production, which ultimately hollowed out manufacturing in much of the country.

Outsourcing was integral to the rise of the electronics industry from its beginning, as it split its labor among three workforces. The engineers and researchers, overwhelmingly white men, had groovy offices and competitive work cultures. At the same time, firms employed huge numbers of factory workers in the United States, right there in Santa Clara Valley. Nearly all of them were women, and many were from countries that had been destabilized by Cold War intrigues. Hiring managers praised “fast fingered Malaysians”; this was not a proud era of American corporate life. Finally, these companies had assembly plants throughout Asia. In Malaysia, the island of Penang became known as “Silicon Island.” Semiconductor companies there established grotesqueries such as the Miss Free Trade Zone competition. This supply chain was notable to people all around the world because it was new and important.

“In California’s Silicon Valley, for example, research and development work is carried out by well paid, usually male scientists and engineers. Circuits are then photographically etched onto layers of silicon in nearby assembly plants by women—50% of whom are Asian or Latin—for low wages in a highly pressurized environment,” wrote the British sociologist Diane Elson for a 1983 conference, Women Working Worldwide. “The new stage is relocated to Southeast Asia where the silicon slices are cut up, bonded onto circuit boards, sealed in ceramic coating and tested. From there components are sent to other third world countries to be assembled into watches, etc., or sent back to the U.S.”

Fairchild Semiconductor, which spawned so many chip companies—including Intel—that they became known as the Fairchildren, began outsourcing parts of its production process to Hong Kong in 1963. By the early 1980s, labor activists at the Women Working Worldwide conference estimated that 50 percent of the people in Asia’s free-trade and export zones were working for electronics companies. And in the years since, the industry’s production has shifted ever more abroad.

Americans at the time noticed these changes, and were troubled by their implications. In the early 1970s, Huey Newton, the Black Panther leader, lived in sight of the Port of Oakland. He wrote an essay titled “The Technology Question,” arguing that the United States didn’t need to occupy and run Korea or Malaysia as colonies. Instead, it could direct the development of such countries from afar, so that they would provide the labor and consumers that the U.S. sought. Newton had a crucial realization about distributed supply chains: Because they dispersed the ethical responsibility for violence, no one even had to buy into the military-industrial complex’s aims. “The U.S. capitalist has been able to spread out his entire operation. You put together his machinery in parts,” he wrote, “thus you are not building a bomb, you are building a transistor.”

Newton told the story of the writer Alex Haley visiting Africa. Haley saw “an old man walking down the road, holding something that he cherished to his ear. It was a small transistor radio that was zeroed in on the British broadcasting network.” The man had a product containing the fruits of Silicon Valley’s R&D, playing the mass media of the empire that had colonized his country. People liked the outputs of this technological system, and its downsides—which might have horrified them—were quite deliberately obscured from view.

For decades, San Francisco was the most important port on the West Coast. Cargoes were loaded and unloaded on finger piers that surrounded the city like a crown. But containerization changed all that. Holding the containers offloaded from ships until they could be taken by semitrucks to their eventual destinations required more land than the warehouses that had once housed such cargo had occupied. Finding hundreds of acres of storage in downtown San Francisco was impossible.

Instead, cargo operations moved across the Bay, where the once-sleepy Port of Oakland bet heavily on containerization. Capturing more of the trade from Asia had long been Oakland’s goal. In 1952, the city released a report on developing its shoreline. “The industrialization of China and the rest of the Orient is late in arriving. Because of its magnitude it will inevitably produce fundamental modifications in the world’s economic and political structure,” the report declared. “No one can say exactly what the impact of the industrial revolution in Asia will be on the economy of the Pacific Coast; the potentialities are beyond imagination.”

The report was not wrong, but delivering on the potentialities took some technological development. From the perspective of men who worked on the docks, there were two components. “Containerization is the technological underpinning of the global economy,” the longshoreman (and political scientist) Herb Mills told a San Francisco historian in 1996. “Because you can bet your sweet ass if all them transmissions was being hand-handled out of the hold of a ship and put on a pallet board and sent ashore, rather than twenty tons of transmissions being in a goddamn container box, transmissions would still be built in Detroit.”

Along with the second component—“computers, rapid communication, inventory control, and all that stuff,” Mills argued—containerization “is why jobs have flowed out of the United States.” Silicon Valley created the technology to make global supply chains work, and containerization made them practical. The Bay Area’s manufacturing jobs flowed overseas, and manufactured goods flooded back through Oakland.

Of course, goods don’t move themselves, even in a container. That takes a diesel truck. And if thousands of boxes are suddenly coming into a port, that means thousands of trucks will be too.

In Oakland, the neighborhood that had to absorb the influx of trucks to move the goods was overwhelmingly Black and quite poor. Since the 1930s, the city of Oakland had been trying to push out the mixed-race residents of the neighborhood to make way for industrial development. The city-planning engineer I. F. Shattuck recommended two strategies. One: Racially segregate the area by building a highway. That was largely successful. And two: Continue to site heavy industrial facilities in the area near the port to crowd out the residents. That was only half successful. The industry came, but the people stayed, despite deteriorating conditions. When more Black people came to Oakland during World War II for wartime jobs, many found themselves confined to the neighborhood by discrimination.

Beginning in the late 1950s, under the guise of urban renewal, the city bulldozed huge chunks of the area’s main commercial strip, Seventh Street, destroying the commercial base of the Black community. It never recovered. The city of Oakland had declared chunks of the area blighted using a supposedly race-blind formula. In retrospect, it was more of an index statistic of environmental racism. The city’s elites had found a way to declare the areas where 98 percent of Oakland’s Black residents lived to be blighted, which, as the legal scholar Wendell Pritchett has argued, robbed everyone of all races who lived in those areas of their property rights. Versions of the same story played out in other Black neighborhoods that were adjacent to ports.

The Pacific Circuit has one more link. As the U.S. pushed countries to develop export-oriented economies, many of those countries found it advantageous to hold dollar-denominated assets. One reason that Americans have been able to take on debt is that many other countries have been more than willing to hold mortgage-backed securities and other financial instruments. With so much juice flowing through our real-estate system, it’s no wonder that prices have spiraled upward.

In the years after the Great Recession, rising real-estate prices in urban areas led many white Americans to buy homes in Black neighborhoods—in places like West Oakland. That is to say, the Pacific Circuit helps underpin gentrification, which has upended our cities in ways that we’re still figuring out.

The share of wealth held by the bottom 50 percent of Americans has not increased in the past 40 years. Many of our indicators of Black-white inequality are as high as they were in the mid-1960s, just a few years after the legal dismantling of Jim Crow. In America’s port cities, the professional classes have gained high-paying jobs, abundant credit, and appreciating home values. At the same time, the working classes have seen their jobs go overseas and their neighborhoods become unaffordable.

Oakland has a way of concentrating the power and problems of our country. As I worked on my book over the years, I couldn’t help but notice a bifurcation in my experience of this place. Many of my affluent neighbors are coming to see themselves more as nodes in a network of deliveries and pickups than as citizens of a specific place. Apps are making all kinds of services better and more convenient, even as they deepen our dependency on far-off companies and countries. But all this convenience comes at a steep cost. Oakland is struggling to provide essential public services, the kind that can’t be ordered up on an app. The superstar cities that once seemed immune to the emptying out of Main Streets across the country are now experiencing their own version of what happened to rural areas during Walmart’s expansion. Take a trip around Oakland’s downtown, and you’ll see the vacant storefronts.

After 50 years, the Pacific Circuit has become so powerful that it is breaking our cities. Many city officials and local entrepreneurs keep waiting for the effects of the pandemic to wear off, for the streets to refill and for the old normal to return. It might not. The pandemic pulled forward a structural alteration in the urban economy. Each DoorDash order that gets delivered or Amazon package that gets left on a doorstep makes running a local business that much harder. The old spatial order of the city is now overlaid by a digital one that’s linked to the global economy through companies such as Temu and Uber and Apple. What might be wonderful for an individual (so convenient!) has generated a collective crisis of the city.

Will Donald Trump’s tariffs change all this? I doubt it. Perhaps some other countries and trading partners will benefit, but the realities of the labor arbitrage that the longshoreman Mills observed remain. Even our most successful domestic manufacturers now rely on components manufactured all over the globe.

Could we, as consumers, simply stop using the logistical apps that have burrowed their way into our hearts and habits? I’m reminded of the man Alex Haley met. We love the outputs of the Pacific Circuit, despite their negative effects on the places we live.

In the 2010s, only one coffee shop stood on the west end of Seventh Street. Sometimes it seemed to be called the Seventh Street Cafe, other times the Revolution Cafe. If it was open, jazz was usually playing. The walls were adorned with old Black Panthers paraphernalia, a Malcolm X poster, an Aztec god, and the symbol for the artist formerly known as Prince. The café was attached to a big open lot filled with old furniture and little improvised structures on the verge of collapse.

The café, however, had almost nothing for sale. One time I went in and found a black-beanie-wearing Katrina refugee named Cedric tending the place. He was serious, smart, and had the sort of dark view of America you might expect from someone who got out of New Orleans because he thought the levee was going to break. I told him about the book I was working on. “Technology always gonna have a downside,” he said. He compared it to sci-fi shows. “It’s like when they go out in space and shit and they be looking for stuff and then they bring it back here and the people say, ‘We didn’t want that shit! Why you go out looking for that shit?’”

No one asked for this world, and yet here we are. Trucks rumbled by. I was the only customer. I wanted to support the place, so I tried to order food, but despite the extensive menu on the wall, all they actually had was coffee and day-old coffee cake. So that’s what I bought.

This is how local businesses work. You buy something for a few dollars—cake, coffee—and then you sell it, maybe, for a few dollars more than you bought it for. Do it a few times, and you can pay Cedric. Do it a few more times, and you can keep the doors open. This is the economy as we like to imagine it.

But this is not how everyone makes money. Private equity firms, hedge funds, and venture capitalists take in money from public and private pension funds, Middle Eastern sovereign wealth funds, insurance companies, huge asset managers, university endowments, and banks. In 2023, the world’s largest asset managers had more than $113 trillion under management, and they are willing to scour the earth to increase their returns.

While places like the Revolution Cafe have to rely on individual residents of West Oakland to come in and spend $3 so they can make 50 cents, companies such as Alphabet or Meta are not constrained by geography. They can show ads to the entire world, extract money from the internet, and pull the bulk of it to their headquarters.

Or take Uber, which took in billions of dollars of investment in the 2010s, a large chunk of it through the Japanese SoftBank, which itself drew funds from Saudi Arabia’s sovereign wealth fund. Uber was deliberately losing money to keep fares low to juice its growth; in a very real sense, when you took an Uber ride, the cost of your fare was subsidized by pumping oil out of the ground in Ghawar province of eastern Saudi Arabia. How can a regular cab company compete with that?

Even the companies operating out of the Port of Oakland have almost no relationship to the neighborhood economy anymore. The shipping and stevedoring outfits are headquartered in Asia or Europe. The goods they import and export almost all come from somewhere else. Oakland captures some tiny trickle of funds, but the big money flowing through the port exists on another plane of economic existence, inaccessible to anyone in West Oakland except through the very narrow conduit of dockwork, where the longshoremen who remain capture a tiny percentage of the value of the goods passing through as wages.

Battles over urban change tend to take on a cultural cast—coffee shops and dog walkers replacing barbecue joints and barbers. The real disagreement, though, is not over lattes but over whether a rising tide lifts all boats. And in city after city, the rising tide looks more like a flood. It is more than metaphor that the homeless encampments, filled with flotsam and jetsam, look like the remnants of a natural disaster. They are testament to our emergency. If you’re poor, there’s little you can do to stem the forces reshaping cities except wait and watch for the signs of change, disturbances in the wind or the tastes of the air that say Get out now.

We need a new way of talking about what’s happening in cities, one that faces the realities of the world that the pandemic accelerated into being. We might like to think that our individual behavior is separate from the decisions made by the technology companies, the flow of global supply chains, the dynamics of the real-estate system, or the racial history of cities—but it is not. City dwellers, rich and poor alike, are stuck in a set of systems that are generating ever rising housing costs, mass homelessness, displacement, and an attenuated urban life.

The fates of the residents of superstar cities are more connected to Main Street America and its workers than many think. And in that realization lies the potential for a different political coalition that can make a different set of choices.

The Polish theorist Zygmunt Bauman argued that we now live under conditions of “liquid modernity,” by which he meant that power no longer has handles that regular people can grab onto. Power and capital, when confronted, simply move, flowing to less challenging, less democratic places with cozier tax structures. To slightly paraphrase Bauman, we now live in a world where it often feels as if anything can happen but nothing can be done.

But some people have figured out ways to get a hold on power. All these liquid systems have to make contact with the physical realm at some point, and such chokepoints can have an outsized effect. Longshoremen’s power derives from controlling labor, and the ILWU has organized all the ports on the West Coast, creating a network that accounts for liquid power. The anti-fossil-fuel activists of the No Coal in Oakland coalition have stymied the creation of a bulk-export terminal in West Oakland. Climate change is a global issue, but it’s local activists who have kept coal in the ground in Utah.

Similarly, organizations such as the East Bay Permanent Real Estate Cooperative are pulling land, housing, and commercial properties out of liquid real-estate markets. They are separating property’s role as an asset from its role as a vital component of civic life, be it a roof over your head, a wildlife corridor, or a legacy business.

These organizations are acting locally, but their interventions take into account the nature of global power. That’s the lesson from the ports and docks. Liquid power and capital eventually have to touch the land, and when local action takes place in those places, the activists and reformers can use the circuits that supercharge our economy to scale their own impact.

This article has been excerpted from Alexis Madrigal’s new book, The Pacific Circuit.

By Alexis Madrigal

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

Premium IPTV Experience with line4k

Experience the ultimate entertainment with our premium IPTV service. Watch your favorite channels, movies, and sports events in stunning 4K quality. Enjoy seamless streaming with zero buffering and access to over 10,000+ channels worldwide.