This is an edition of Time-Travel Thursdays, a journey through The Atlantic’s archives to contextualize the present. Sign up here.

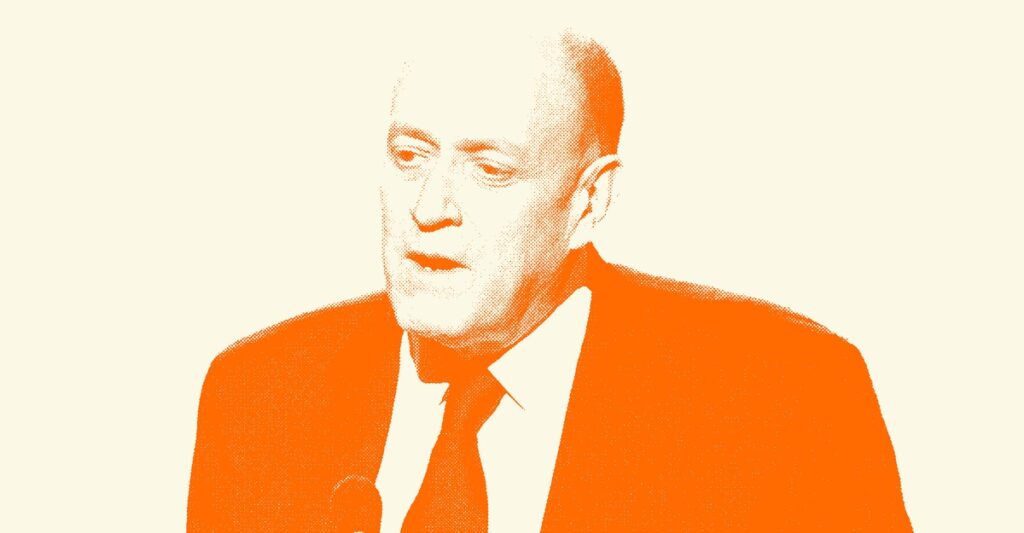

“Jazz has absorbed whatever was around from the very beginning,” the writer Francis Davis told Wen Stephenson in a 1996 interview. The same might have been said of Davis, who died last week at 78. Nate Chinen, writing for NPR, called Davis “an articulate and gimlet-eyed cultural critic who achieved an eminent stature in jazz.”

Davis wrote for The Atlantic for more than three decades, from 1984 to 2016, and was a contributing editor for much of that time. He also had a high-profile stint at The Village Voice, where he originated an annual jazz critics’ poll that continues today elsewhere and now bears his name. (His influence can also be detected on NPR’s Fresh Air, which is hosted by his widow, Terry Gross, and where he served as the program’s first jazz critic.)

Corby Kummer, a longtime Atlantic staffer who edited Davis, told me that one thing that set Davis apart was how catholic his taste was. “There were no avant-garde novels or musicians or art-house movies he didn’t know, and he knew absolutely everything mainstream,” Kummer said. “He was high-low before ‘high-low’ was a concept. He took everything into account.”

You can see Davis’s breadth in, for example, his 1992 rave review of Seinfeld, which doubles as an erudite history of popular television. “So much in Seinfeld is new to TV, beginning with its acknowledgment of the absurdity in the ordinary, that you tend to forget that it’s based on a premise as old as the medium,” he wrote. Twelve years later, he wrote a moving eulogy for Johnny Cash, “a Christian who didn’t cast stones, a patriot who didn’t play the flag card.”

But Davis’s jazz writing stands out the most, and means the most to me. He came to The Atlantic under the direction of the editor William Whitworth. As my colleagues Cullen Murphy and Scott Stossel wrote in an obituary last year, Whitworth was a serious jazz fan who had also been, in his youth, a serious trumpeter; he eventually chose a journalist’s life over a musician’s. Davis “might have been Bill’s favorite writer,” Kummer told me. The two men would trade album reviews and listen to music together, and Whitworth gave Davis wide latitude to follow his interests.

That might help explain how, in the same calendar year, Davis published deep and definitive profiles of Benny Carter, an alto saxophonist who had been recording since the 1920s, and John Zorn, an impish and sometimes earsplitting avant-garde composer who shared little with Carter save the alto sax and the imprecise label of jazz. “Zorn, in short, is exactly the sort of rude, overgrown adolescent you would go out of your way to avoid, if only he weren’t so … well, interesting, important, and influential (at least potentially),” Davis wrote. (Davis’s prediction has borne out: Zorn remains a central and only slightly calmer figure today.)

Davis lamented that the music he loved was viewed as elitist, but he wrote about it in terms that could reach both serious fans and casual listeners. His confiding but lightly sardonic presence on the page brought you in, and his ability to translate jazz into plain English brought you along. In 1988, he captured how the members of the trumpeter Wynton Marsalis’s band “sound as though they were playing in four different time signatures. But actually they are stretching a basic quadruple meter four different ways, accenting different beats in every measure, and trusting that the listener will feel the downbeat in his bones. The effect is mesmerizing.”

Davis’s fundamental interest, though, was less musicological than anthropological. “What does music mean to people?” he wondered. “What does it signify to them?” I’ve always loved his description of the deceptively relaxed guitarist Bill Frisell: “Even at its most melodic and high-stepping, Frisell’s music seems haunted and disquieted, more Edward Hopper than Grant Wood or Norman Rockwell, evocative not just of rivers and prairies and small-town parades but of lost highways, dead-end streets, and heartbreak hotels.”

Although Davis could write an immaculate sentence, his goal was not flash or provocation. “He wasn’t interested in being a cultural authority,” Kummer told me. “He was interested, as the best writers are, in understanding what he thought by writing it out.” This meant that when he did make a judgment, it carried a great deal of weight. His verdict on Marsalis’s retrospective orientation feels as solid now as it did 37 years ago: “Progress is frequently a myth in jazz, as in most other aspects of contemporary life. But it is a myth so central to the romance of jazz that the cost of relinquishing it might be giving up jazz altogether.”

The sureness of Davis’s judgments makes me hesitate to contradict him, but I must. What I believe was Davis’s final published piece was an essay in January that accompanied his eponymous poll, in which he disclosed that he’d entered hospice. His outlook on jazz journalism was grim. “Maybe I was the last to learn that criticism had outlived its usefulness as far as the arts and entertainment industry were concerned,” he wrote. “Or maybe only I have outlived mine.” On the contrary, his criticism has and will outlive him, much to the benefit of the listeners and readers who do too.

Premium IPTV Experience with line4k

Experience the ultimate entertainment with our premium IPTV service. Watch your favorite channels, movies, and sports events in stunning 4K quality. Enjoy seamless streaming with zero buffering and access to over 10,000+ channels worldwide.