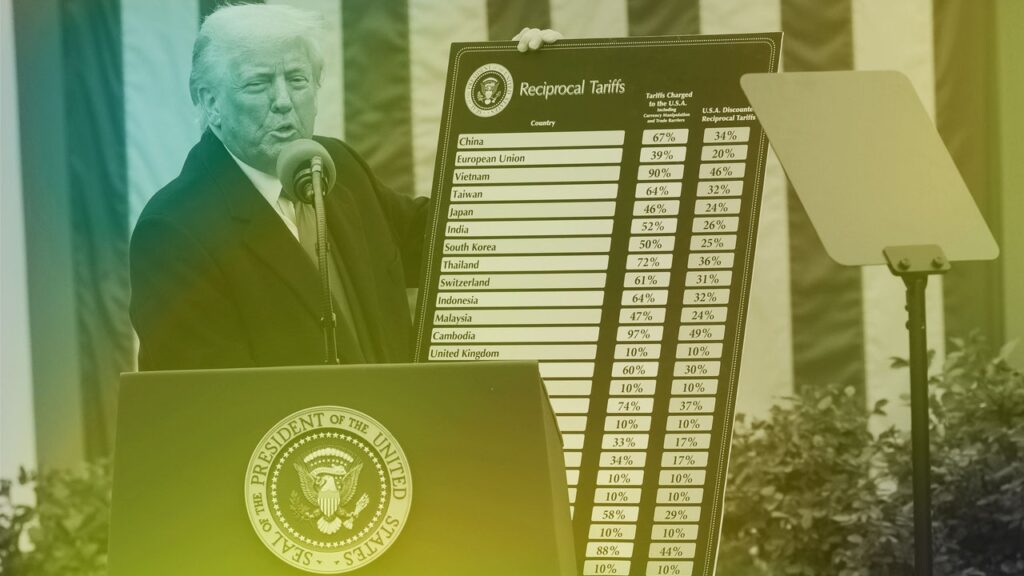

After weeks of nervous anticipation in the financial markets and in the capitals of America’s trading partners, Donald Trump’s “Liberation Day” tariffs have arrived, and, even by his standards, they are shockingly high and wide-ranging. “For decades our country has been looted, pillaged, raped, and plundered by nations near and far,” Trump said on Wednesday to a crowd at the White House that included members of United Auto Workers, and also elected Republicans. After delivering a potted economic history of the country in which he bizarrely claimed that the Great Depression would have been avoided if high tariffs had been in place, Trump announced that “reciprocal tariffs” would go into effect on April 9th, with rates of thirty-four per cent on goods imported from China, twenty-four per cent on Japan, and twenty per cent on the European Union. Some of the highest rates were reserved for export-led developing countries in Asia: forty-six per cent on Vietnam, forty-eight per cent on Laos, and forty-nine per cent on Cambodia.

The run-up to the announcement was chaotic. Trump has long been obsessed with tariffs, of course, but recently he has issued mixed messages, at one point suggesting the new tariffs would be “somewhat conservative.” A couple of weeks ago, there were press reports that he had settled on a relatively narrow approach, targeting only countries that run large trade surpluses with the United States, such as China and Japan. Last weekend, it emerged that universal tariffs, of the sort he talked about in last year’s election campaign, were back on the table. “No one knows what the fuck is going on,” a source close to the White House told Politico. “What are they going to tariff? Who are they gonna tariff and at what rates? Like, the very basic questions haven’t been answered yet.”

Ultimately, Trump chose an “all of the above” option.” The new tariffs involve a levy of ten per cent on virtually all imported goods, plus higher levies on many individual countries. Trump claimed the rates were roughly half of the tariffs that these countries impose on U.S. goods, but the details of how they were arrived at weren’t immediately available. While many countries do have higher tariffs than the United States, the differences aren’t as big as Trump claims, especially for some of America’s allies that he has targeted. “On a trade-weighted basis, the average U.S. tariff is 2.2 percent,” the Washington Post’s Jeff Stein and David J. Lynch noted. “Japan’s is 1.9 percent and the European Union’s is 2.7 percent, slightly higher than the U.S. average, according to the World Trade Organization.”

The levies Trump announced on Wednesday are separate from the ones he has already imposed on steel, aluminum, and foreign-made cars and parts. Taken as a whole, his tariffs represent a dramatic expansion from the more narrowly targeted duties he imposed in his first term—some of which the Biden Administration retained—and a final nail in the coffin for the open trading environment that reigned before 2016. According to Olu Sonola, an economist at Fitch Ratings, the average U.S. tariff rate on all imports will be around twenty-two per cent, a rate last seen around 1910. “This is a game changer, not only for the US economy but for the global economy,” Sonola said in a statement. “Many countries will likely end up in a recession.”

Some accounts of Trump’s approach to trade, including mine, have identified William McKinley, the twenty-fifth President, as an inspiration. Other commenters have suggested that Hitler’s Germany, which pursued an economic policy of self-sufficiency, or autarky, may be Trump’s real role model. Wherever he got his love of tariffs and protectionism, the intellectual antecedents of his approach go back to English mercantilist thinkers of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, who also viewed trade as a zero-sum enterprise in which one side wins and the other loses. “For we must alwaies take hede that we bie no more of strangers than we sell them; for so we sholde empoverishe our selves and enriche them,” an anonymous English author wrote in the fifteen-fifties. The aristocrat William Cecil, a senior adviser to Queen Elizabeth I, sounded even more Trumpian. “Nothing robbeth the realm of England, but when more merchandise is brought into the realm than is coming forth,” he averred.

At a time when trade was largely financed in gold and silver, the mercantilists thought of it in terms of accumulating wealth, or “treasure.” Trump thinks in terms of dollars rather than gold, but little rests on that distinction. In his remarks on Wednesday, he repeated his unfounded claim that Canada was subsidizing the United States to the tune of two hundred billion dollars a year. (Trade payments aren’t subsidies, and last year the U.S. deficit in trade on goods and services with Canada was well under a hundred billion dollars.)

After China joined the World Trade Organization, in 2001, and cheap Chinese goods flooded into the United States, it was amply demonstrated that open trade with countries that have much lower labor costs can devastate some communities and industries. For a long time, American economists understated these costs, relying on Adam Smith’s argument that trade is mutually beneficial because it allows each party to exploit its natural endowments and skill sets. (The famous example that Smith cited was Britain exporting cloth to Portugal and importing Portuguese wine.) In Washington these days, the economic debate has largely moved on to which departures from free trade can be justified. The Biden Administration, for example, quadrupled the tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles and provided generous grants for auto companies that invest in building E.V.s in the United States.

Trump’s tariffs are much broader, and they will affect many of America’s historical allies. Inevitably, this has given rise to speculation about his ultimate goals. In a paper published immediately after last year’s election, Stephen Miran, a Harvard-trained economist who was then working for a hedge fund and is now chair of the Council of Economic Advisers, tied Trump’s tariff proposals to his America First foreign policy, suggesting they could be part of a grand strategy to reduce the U.S. trade deficit and simultaneously force America’s allies to share the burden of its defense umbrella and national debt.

As Miran described it, Trump’s tariffs would function primarily as bargaining chips, which he could use to browbeat other countries into accepting a devaluation of the dollar, which would make U.S. exports more competitive, and a refinancing of the U.S. national debt, in which foreign debt holders—of which there are many—would swap their Treasuries for a new type of security: a hundred-year bond that carries a very low-interest coupon, thus making it cheaper for the U.S. government to raise money.Why would foreigners accept such an unfavorable deal? Miran didn’t fully explain, but the inference is that they wouldn’t have any choice if they wanted to retain access to the U.S. market and military support. Miran termed this prospective rearrangement of the international trading system as a “Mar-a-Lago Accord”—a play on the Plaza Accord, of 1985, in which the U.S., Japan, Germany, France, and the U.K. agreed to a dollar devaluation on a voluntary basis. As Martin Wolf, of the Financial Times, pointed out, the Trump version, if it ever came to pass, could more accurately be described as a protection racket.

Trump didn’t mention any of this on Wednesday. Instead, he claimed that the tariffs would lure manufacturers back, create jobs, and raise a great deal of money in new revenues. But employing tariffs as permanent sources of revenue clashes with the idea of using them as bargaining chips in future trade agreements. Another issue with the idea of a Mar-a-Lago Accord, or something similar, is that any serious suggestion that the United States was seeking to refinance the twenty-five trillion dollars of its debt that is held by private investors could very well produce the mother of all runs on Treasuries, and a major financial crisis.

The immediate political challenge for Trump is that, regardless of the prospects of his policies boosting U.S. manufacturing over the long term, in the short term they are likely to inflict pain on two major constituents of the G.O.P. coalition: working-class MAGA voters and Republicans in business.

While some of Trump’s supporters may cheer him for trying to protect the industries and communities they work in, they will now pay higher prices for everything from clothes and electronics imported from Asia, to French wines and Irish whiskey, to cars built inside and outside the United States. The tariffs of twenty-five per cent on foreign auto vehicles and parts, which were announced last week, will go into effect on Thursday. Daniel Roeska, an analyst at Bernstein, has estimated that they could raise costs for automakers, who rely on parts made abroad, by sixty-seven hundred dollars per vehicle sold.

Premium IPTV Experience with line4k

Experience the ultimate entertainment with our premium IPTV service. Watch your favorite channels, movies, and sports events in stunning 4K quality. Enjoy seamless streaming with zero buffering and access to over 10,000+ channels worldwide.