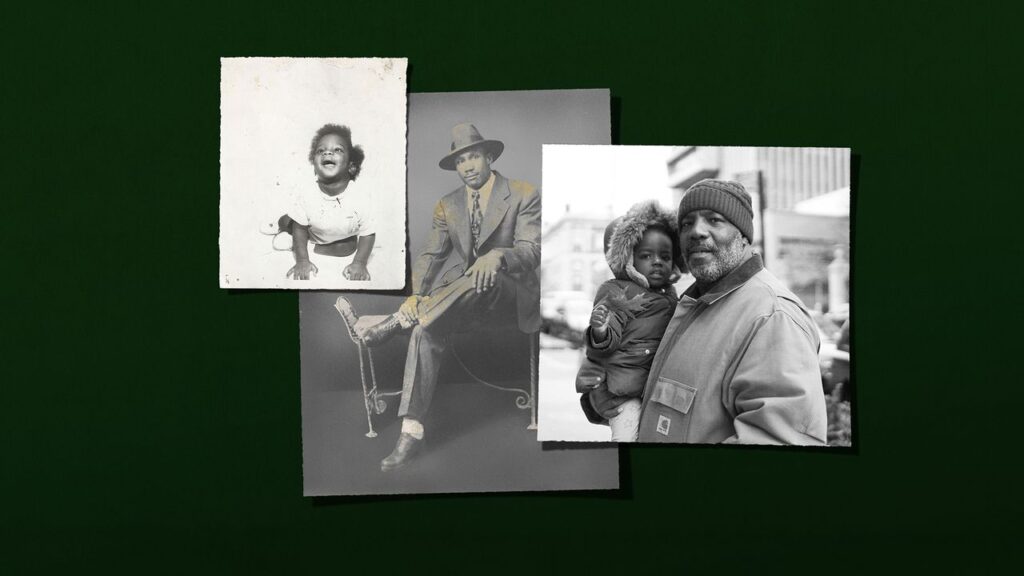

Forty-nine years ago, on what I recall as a Saturday morning when I was six and my father was fifty-six, I barged into the bathroom, as was my habit, and witnessed a scene that both bewildered and fascinated me. Our nineteen-seventies-era yellow-orange sink was covered in thick black streaks, as were parts of the countertop. My father, a formidable man who had been a heavyweight boxer in his youth and retained his imposing physique well into his sixties, hulked over the faucet. He turned to me, and I saw that his mustache and upper lip were stained the same color as the countertop, as was a portion of his normally salt-and-pepper hair. To his right was what appeared to be a cup of ink, and he periodically dipped a comb into it and gingerly pulled it through his hair. I was already, at that age, an expert eavesdropper, and an enigmatic sliver of conversation that I’d overheard a few days earlier began to make sense. My mother, whose preoccupations included Telly Savalas, an icon of seventies television who’d shown that baldness, and therefore middle age, could be a selling point in the right man, had said to my father, “You should keep your gray. It looks good on you.” I had never seen my father’s hair any other color but gray, so it had not occurred to me that there were options. The scene playing out in the bathroom was clarifying. The ritual completed, my father assessed himself in the mirror. The still-wet strands glistened as if he’d just stepped out of an ad for Afro Sheen. The dyes of that era were not like the subtle modern versions. They were blunt instruments wielded against the most obvious sign of aging. The concoction in the cup had made my father’s hair unnaturally, propagandistically black. His camouflage stood out. He did not look like a man with dark hair; he looked like a man with gray hair who had dyed it black. I decided that I agreed with my mother. “I like the gray better,” I told him. “Yeah?” he said. “Wait until you get some.” Then he chuckled, knowingly.

I replayed that conversation years later, when I was twenty-nine, and a single recalcitrant gray hair showed up in my beard. I replayed it again in my early thirties, when a colony of them formed a streak on my chin, and again in my forties, when a friend described me as having a “salt-and-pepper beard.” The sight of it each morning increasingly reminded me of a data visualization of a gentrifying neighborhood. I thought about the dye incident most recently a few weeks ago, when August, the elder of my twin sons, by nine minutes, bounded into my lap and insouciantly asked why my beard was so gray. He is five, and I’m fifty-five. My hair is gray because I’m trying to win an argument with your long-deceased grandfather, I thought. His twin brother, Hollis, who is earnest to a fault, is consumed with simpler questions: “Daddy, are you stronger than a bear? Can you pick up a whole car? What about a house?” He awaits the answers as if trying to understand what station in the Marvel Universe I should occupy. Before I could start talking to August about hair follicles that gradually lose their ability to produce melanin, he answered his own question. “I know why. It’s because of age.” Yeah, I thought, just wait until you get some, and laughed at my own cleverness. A therapist friend once told me that people frequently strive to become their parents or their unparents, using them as role models to be emulated or as a negative road map of what is to be avoided, or sometimes both, simultaneously. I contrasted my father’s approach to aging by allowing time to mark its passage as it sees fit, but I echoed him in a much more profound way—by having young children at a point when that passage had already become apparent.

If the data for 1972—the earliest year covered by a recent study on the subject—holds true for 1969, then roughly half a per cent of American babies born that year were born to fathers who were at least fifty years old. I was one of them. Maternal age has been a subject of fixation since the Biblical Sarah gave birth to Isaac, purportedly at age ninety, but the age of fathers has generally been a lesser concern. (Sarah’s husband, Abraham, according to the Bible, was a hundred years old at the time of Isaac’s birth.) The age of American women at the birth of their first child has ticked steadily upward for decades, driven, in part, by the increasing number of women entering the workforce and seeking professional degrees, as well as by broader access to contraception and advancements in fertility treatments. The trend is a rough barometer of women’s progress and the evolving vista of possibilities in their lives. Almost surreptitiously, though, the age of American fathers has crept up, too, often in concert with the same dynamics that have changed women’s reproductive timetables. Men of “advanced paternal age,” as the literature refers to those of us who were over forty when our children were born, account for more than twice the percentage of births than they did in 1972. The landscape of older fatherhood has begun to look different from the one I was born into or the one represented by my own family structure. The widespread availability of I.V.F. treatments has contributed to a decrease in the age gap between older men and the women who have children with them. The portrait of the seasoned father is increasingly a middle-aged man whose age-peer partner has given birth with the assistance of reproductive technologies.

In 2019, the year my twins were born, the share of American babies with fathers who were fifty or older was almost triple what it was on the morning when my parents, Willie Lee and Mary Cobb, brought me home from Mary Immaculate Hospital. This is still a modest number—less than two per cent of the total—but the number of children born to men who were forty to forty-nine more than doubled during that same timeframe. The average age of fathers has increased by more than three years in the past four decades. The punishing economics of the labor market and housing costs that young people are trying to navigate may further exacerbate the trend. As with most things, men and women have received contradictory messaging about it. For men, particularly in the years before erectile medications hit the market, older paternity was tacitly perceived as a nod to enduring virility. For women, however, older maternity comes freighted with warnings. Pregnancies occurring in women over the age of thirty-five—“geriatric pregnancies,” as they used to be called—are associated with slightly higher risks of miscarriage, stillbirth, and a number of genetic disorders. Not until comparatively recently has medicine begun to catalogue the health concerns associated with a father’s advanced age, and there are a number of them, including somewhat higher incidences of autism and of diagnoses of schizophrenia later in life. Some research also suggests that children of older fathers tend to score higher on I.Q. tests and may also have advantages when it comes to longevity. A friend who taught high school for years remarked that the students with the broadest frames of reference were consistently those who had older parents. My father and I did not follow the exact same pattern. He had two sons across two generations, born into separate marriages; I married young and helped raise a stepdaughter, but did not have biological children until I was forty-seven, and engaged to my wife, Danielle, who is fifteen years my junior—when our daughter, Lenox, now eight, was born. I have considered this phenomenon from both sides of the ledger, as the child of an older father and the older father of children. The growing preponderance of gray dads marks both the prerogatives of maleness and greater gender equality. Willie’s version of this story, on some level, reflected both these dynamics.

My father grew up in a speck of a town called Hazlehurst, Georgia, which is about two hours west of Savannah. It doesn’t seem to have changed much from the place he used to talk about; a few years ago, a resident described it on a website as a small, peaceful place that “unfortunately, has very few things to do for entertainment.” The 1920 census lists Willie Lee’s family as “mulatto,” but the 1930 census describes them as “Negro.” A bit of mordant familial humor held that the Great Depression had hit the year before, and the family had been demoted, but the new categorization was more likely the product of the family’s changing structure. My paternal grandfather was a large man, even taller and broader than my father. He was born with blue eyes and was nearly light enough to pass for white. His grandmother was said to have been a white woman from England who had taken up with a Black man in North Carolina just after slavery ended. My father’s parents had married in their teens, but split during his childhood, leaving his darker-complexioned mother, whose family had come from the Georgia Sea Islands, as the head of household when the 1930 census was conducted. My father, the eldest boy of their four children, left school at eight or nine to help earn money in his father’s absence. In his late teens, he moved to Miami, where his father had relocated, and took up boxing, but he quit when he was pressured to throw a fight.

After a stint in the Army, Willie Lee migrated to New York City, where he worked as an electrician. Not long after his arrival, he ditched his given name, which he considered a hick handle, and renamed himself Al—people sometimes called him Big Al—which he thought sounded sharp and urbane. After a few years, he married a woman named Carol, whom he’d known growing up in Georgia. They settled in Harlem and had a son who was born on my father’s twenty-seventh birthday, and named him Alan. They split up before Alan turned ten, and, in a decision that seemed uncommon at the time, my father became the primary custodial parent. The explanations for this arrangement varied over the years, but it was generally accepted that Alan, a virtual replica of our father, was happier living with him. My parents met years later, in the early sixties, when my father was summoned to fix an issue with the wiring in a building on St. Nicholas Avenue, where my mother lived. She was a newly divorced single mother of two in her early twenties, and he was a not-so-newly divorced single father in his mid-forties. According to the familial lore, he completed the work and left only to knock on her door five minutes later to ask for a light. She handed him a book of matches and closed the door, but he knocked again thirty seconds later, coyly complaining that the matches were wet, but also making no effort to hide his interest. He then confessed that he’d asked for the matches in an attempt to “strike up” a conversation with her. (“Smooth,” he later said of his opening play.) They exchanged numbers and began dating. My mother later told me that she liked my father’s good looks and his sense of style, but was truly impressed by the fact that he was raising a son virtually on his own. They married and bought a house on a quiet street in Hollis, Queens, about two years later.

The blended family included Alan, who was drafted to fight in Vietnam not long after I was born, and my mother’s children, Valerie and Victor, who were, respectively, ten and seven years older than me. I came along as a quiet testament to my parents’ hope in second chances or, in my father’s case, as we later learned, maybe even third ones. My parents were the products of particular histories—his decision to leave Hazlehurst, Georgia, and hers to leave her home town of Bessemer, Alabama; their previous, failed relationships; the ambitions that had already been foreclosed and those that remained in play—but to the world they presented as something common, even anticipated: a middle-aged man and his much younger second wife.

I was, in fact, a surprise. My mother had endured a difficult pregnancy with Victor, and her doctor suggested that she would not be able to carry another pregnancy to term. An overheard comment, in which my mother joked to a friend that my birthday fell almost exactly forty weeks after my father’s, told me more than I ever needed to know about the circumstances of my conception. Older dads are frequently the fathers of children who belong to different generations. Somewhere in elementary school, I noticed that my friend’s fathers were not much older than Alan. When I tagged along on my father’s trips to the electrical-supply house, he would quickly introduce me as his youngest child, which had the effect of preëmpting questions about whether he’d taken his grandson out for the day.

Early on, there were less than subtle signs that my father was parenting with an eye on the clock. On a random afternoon when I was ten and my father was sixty, to my great and incredulous horror, he sat me down and delivered a protracted lecture on the human menstrual cycle. The talk elided any reference to the mechanics of reproduction—this was not the talk—but was an otherwise wide-ranging explication of the subject matter, drawing on the Book of Genesis, personal observations, and popular mythology. “The bleeding happens once every month,” he told me. “And if it doesn’t happen it means the woman is going to have a baby.” He concluded with a cryptic reference to this information being vitally important to me in the future. In retrospect, he’d given a completely serviceable explanation that covered the basic biology and timeframes, but at the time I believed none of it. I respected my father but was also just old enough to suspect he did not always have his facts straight. The concept of humans possessing an internal calendar that was somehow capable of determining when roughly a month had gone by was too absurd to be believed—particularly from the person who had helped convince me for half my young life that Santa Claus and the Easter Bunny were real. Next, you’ll try to tell me my left hand knows when it’s 3 P.M., I thought.

Even if his information was true, I could not imagine a world in which it could possibly be relevant to me. Not long before this, we’d had a tiff. He had cooked Sunday dinner, as was his habit, and, upon learning that I’d finished off the roast beef before he’d had any, grew incensed, told me that I’d eaten too much, and accused me of being gullible. That word had appeared on one of my fifth-grade vocabulary lists, and I saw an opportunity to win the exchange. (At that early juncture, I had already spent two more years in school than my father ever would.) “Daddy, gullible doesn’t have anything to do with food. It means you believe anything people tell you.” My father summoned all the indignation he could manage and shot back, “And in my house it means to eat too much!” He was right about that. If, by some unforeseen combination of luck, hustle, and the intercession of the relevant saints, you managed to purchase a home and clothe and feed four children, despite three grades’ worth of education from a Jim Crow schoolhouse in Georgia, it was entirely within your purview to decide the denotations of language on said property. As with his seemingly far-fetched explanation of female biology, this fact was also lost on me at the time, but eventually I came to respect its importance, as well.

For years, I somewhat amusedly thought of that afternoon’s lecture as premature—there are some ten-year-olds for whom it would’ve been apt, but I wasn’t one of them. It later occurred to me that we had not been working on my timetable but his. All parenting is, on some level, a hedge against the inevitable, and my father suspected he was up against a somewhat less forgiving deadline. Having accumulated six decades of experience on the planet, Willie had decided that it was time to begin dispensing his takeaways. If any of it or all of it went over a boy’s head, then he would just have to play catch-up. The period talk was the first in a randomly delivered seminar series that covered boxing (“The position of a man’s feet will tell you what punch he’s about to throw”), cooking (“Sour milk makes the best cornbread”), and electrical work (“You thread a wire into a fixture in the same direction that the screws on the fixture turn, then wrap it in electrical tape”). Other gems were gleaned from his years as a country boy in the Harlem of the nineteen-forties and fifties. “Never let a cop hand you anything,” he told me. “It’s their way of putting your fingerprints on something that doesn’t belong to you.” Or “If a guy bumps into you on the street, it’s not necessarily because he didn’t see you. First thing to do is look around and figure out what he’s trying to mark you for.”

Part of adulthood typically entails deciphering who your parents are, not simply in relation to you but also to the broader worlds in which they exist. That was a more complicated undertaking in my case, because Willie had been an adult twice as long as my peers’ fathers had. The mystery of his prior life was that much more convoluted. Years ago, I stumbled across an undated photo of my parents from the late sixties or early seventies. They’re sitting in what appears to be a night club. My mother is nestled against my father, and his arm is draped proprietarily around her shoulder. He is wearing a crisp suit and leaning back in his chair—a portrait of the player in repose. I had no idea who those people were, not the coquettish woman, clearly smitten with the handsome man next to her, nor the well-dressed gentleman who looked as if he owned the joint. Years after his death, in 1992, at age seventy-three, my father’s younger sister, Naomi, casually remarked that he had been the sharpest dresser she knew. He favored bespoke suits tailored to emphasize the breadth of his shoulders. By the time I began to take note of them, the years had imposed a sober practicality on my parents, particularly my father. The man I knew dressed like a tradesman, perennially prepared to knock down a wall or pull electrical cable.

Understanding him also required grappling with a different set of references. The events that shaped the sensibilities of my friends’ parents occurred amid the tumult of the sixties. Willie’s formative experiences came in the forties and earlier. My friends’ parents romanticized Kennedy, but I grew up hearing my father’s reverence for Roosevelt leading the nation through the Great Depression. Other parents witnessed the March on Washington, whereas my father saw Jackie Robinson don Dodger blue at Ebbets Field. What this translated into between the two of us could not be properly described as a generation gap. We were technically separated by two generations, but this played out in ways that were markedly different from the conflicts that emerged between my peers and many of their parents. My generation came of age as hip-hop was being created and refined. As with every generation of young people, we defined ourselves by what we imagined to be the canonical rejection of the prior generation’s standards. They largely returned the favor, denouncing rap music as noise, but Willie reacted with bemused curiosity, listening to an early LL Cool J record with me and asking, “Now, what is that fella talking about?”

By the time I’d reached adolescence, my father was firmly in his reflective years. He moved through life with less certainty than he’d possessed as a young man and, as a consequence, far less judgmentally. At sixty-five, he was more interested in understanding why someone would prefer to talk than to sing on a record, rather than in rejecting the entire enterprise. There were other, less predictable consequences of his having lived several prior lives, one of which announced itself, in 1985, in the form of a letter from the Veterans Administration requesting clarification of his marital status. Some records indicated that he was married to my mother, Mary, but others listed a woman named Louise as his spouse. My mother, certain that there had been a clerical error, mentioned it to him. The tension that crossed his face when she said the name Louise, she later told me, suggested that there was more to the story. “Louise,” he said, “was my first wife.”

Premium IPTV Experience with line4k

Experience the ultimate entertainment with our premium IPTV service. Watch your favorite channels, movies, and sports events in stunning 4K quality. Enjoy seamless streaming with zero buffering and access to over 10,000+ channels worldwide.