A little more than a decade ago, the video-game designer Davey Wreden experienced a crippling success. In October, 2013, he and a collaborator, William Pugh, released the Stanley Parable HD, a polished and expanded version of a prototype that Wreden had developed in college, and which he had made available, free of charge, two years before. Wreden and Pugh hoped that they might sell fifty thousand or so copies of the new version in the course of its lifetime. They sold that many on the first day. Wreden was twenty-five years old, and he had everything he’d ever wanted: money, success, recognition. He became severely depressed.

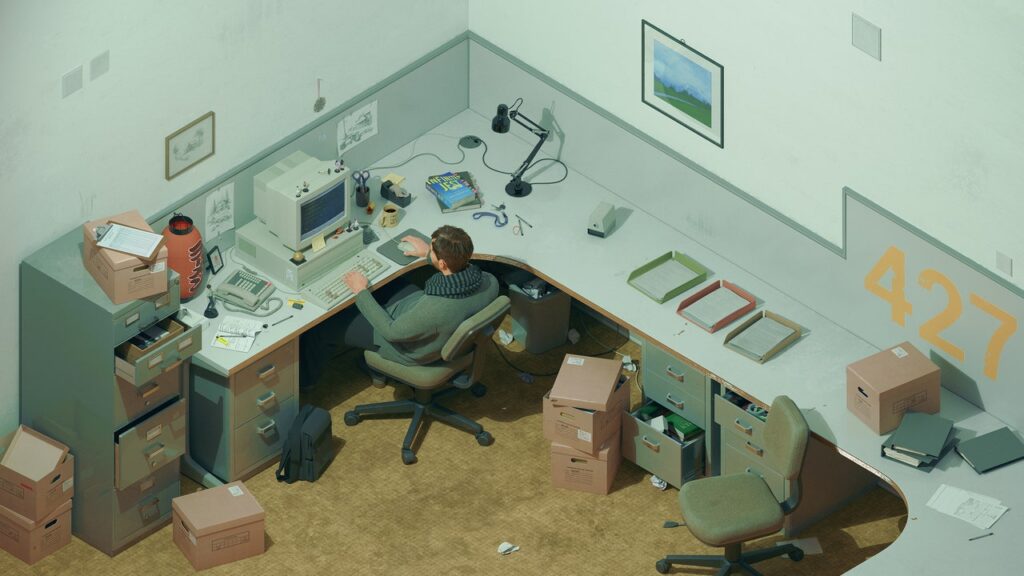

The Stanley Parable is a game about a lonely man. It centers on an office worker, Stanley, who, one day, looks up from his cubicle and discovers that his colleagues have vanished. All that’s left to keep him company is a voice in his head—provided by the British actor Kevan Brighting—which narrates Stanley’s actions. But Stanley doesn’t have to do what the voice says. The game quickly becomes a contest of will between the player and the narrator.

When I first played the Stanley Parable, I was gobsmacked by one sequence in particular, which begins when Stanley walks down a dark corridor marked “ESCAPE.” He finds himself whisked toward a hydraulic press—and certain death, if the narrator’s taunts are to be believed. Just before impact, a previously unheard female narrator (voiced by Lesley Staples) describes how the machine kills Stanley, “crushing every bone in his body.” But the machine doesn’t mush him. Instead, he arrives at a brightly lit museum. Therein lies a small-scale model of his office, with signs explaining how each section was fussed over to insure that the player progresses at a good clip. On the far wall are the game’s credits. The new narrator notes that soon it will be re-started, and Stanley will be alive as ever. “When every path you can walk has been created for you long in advance, death becomes meaningless, making life the same,” she says. Then she adds, “Do you see now that Stanley was already dead from the moment he hit Start?”

I had been playing video games for thirty years, and I had never seen the medium deconstructed so skillfully or with such existential humor. I felt the way that I imagine cinephiles did in 1960, emerging from dark theatres having just seen “Breathless.” The game’s young creators seemed to be free from the trappings of what had come before.

Wreden has since released a second critically acclaimed title, the Beginner’s Guide, and cemented his reputation as a designer who defies convention. Neither of his games asks much more of the player than an ability to move through a 3-D space; what distinguishes them is their philosophical bent and penchant for narrative tricks. (Gabriel Winslow-Yost, writing in The New York Review of Books, invoked Nabokov, calling the Beginner’s Guide “a kind of interactive ‘Pale Fire.’ ”) Among gamers, Wreden has acquired cult-celebrity status, and his influence extends beyond his own medium: even the creator of the TV show “Severance”—another office drama that raises questions about free will as it veers between whimsy and dread—has cited the Stanley Parable as an inspiration. (The game also had a brief cameo in an episode of “House of Cards.”)

Wreden, now thirty-six, has a slim build and a sweep of brown hair. When we spoke for the first time, last year, he was dressed in a dark-gray T-shirt. He works from home, in Vancouver, and the wall behind his desk is adorned with drawings of characters from the video-game franchise Persona, images from the manga Chainsaw Man, and pictures of food. In a corner of the room, next to a bookcase, hangs a ramen-shop paper lantern that he acquired on a trip to Osaka. He was winding down production on his third game, Wanderstop, out this month, and in a reflective mood about its predecessors—works he described as having been designed “to break and unwind the tightly coiled, traditional structure of what games like that were supposed to do.”

As a teen-ager, Wreden loved stories that set traps: “Fight Club” and “The Usual Suspects,” with their late reveals, and works by Roald Dahl and Shirley Jackson. Growing up in Sacramento, California, as the eldest son of a pair of doctors, he gravitated toward brainy but silly humor; he was a big fan of “Weird Al” Yankovic, Flight of the Conchords, and Joseph Heller’s “Catch-22.” Wreden was not an especially happy kid, but from an early age he believed that he could imagine his way to something better. His father once told him that it was hard to have a conversation with him in his adolescence, because Wreden usually forgot what other people said. “It wasn’t, like, a memory thing, or an A.D.H.D. thing,” Wreden recalled. “It was literally just, like, anything that didn’t fit into my big grand plan of doing as much as possible, achieving as much as possible, and thinking as big as possible just wasn’t relevant to me.”

“I’ve had phases of my life where I became not very functional as a person because I couldn’t distinguish myself from the absurdism of the media that I liked,” he said. He responded by creating, in the Stanley Parable, a realm where he could safely explore his own anxieties. “It can’t hurt me because I own it,” he explained. “I thought that if I made a game that spits in the face of an attempt to find meaning in the world, that it would somehow map onto me, as a real person, and I would get over my fear of meaninglessness in the world. And it did not work.”

Wreden has since become ambivalent about the Stanley Parable, feeling, he said, “like a guy who had gotten rich making jokes about video games, trying to deceive real writers into thinking that I’m a real writer.” There was also the shadow of the period after its release, when he became, as he put it, “addicted to praise.” He responded to every piece of fan mail—and hate mail—he received, convinced that any endorsement, rejection, or misapprehension of the game was really about him as a person. Mood swings and sudden bouts of rage alienated his best friend (and then roommate), Robin Arnott, the sound designer for the Stanley Parable, who finally confronted him and said that he couldn’t be around Wreden in this state any longer. Wreden went to therapy; gradually, his depression lifted. The Beginner’s Guide includes a line first spoken by Arnott during the argument that snapped Wreden out of his funk: “When I’m around you, I feel physically ill.”

The Beginner’s Guide was partly inspired by William Goldman’s novel “The Princess Bride,” which Wreden had read while working on the Stanley Parable. Just as the book’s narrator purports to offer an abridgment of a story he’d loved as a child (albeit with plenty of his own editorializing), Wreden thought he might design a documentary-style work around an imaginary game; he was confident no one had done that before. But it was also something far more personal: a game infused with his newfound awareness of the fraught relationship between artist and audience that, as he put it, came from “the deepest place that I could go to within myself.”

In the opening minutes, Wreden—himself a central character—tells the player that he wants to share the work of his friend Coda, an experimental game designer who got his start by tinkering with the same suite of shareware tools that the real-life Wreden had used to create the Stanley Parable. As the Beginner’s Guide progresses, we watch his output grow conceptually richer and more surreal. One of Coda’s games features an outdoor staircase attached to a windowless skyscraper that leads to an inviting wood-panelled room where ideas for new projects float in the air in the form of short sentences. Another level hems the player in with blocks of self-questioning text while the sound of someone gasping for air drones on in the background.

Premium IPTV Experience with line4k

Experience the ultimate entertainment with our premium IPTV service. Watch your favorite channels, movies, and sports events in stunning 4K quality. Enjoy seamless streaming with zero buffering and access to over 10,000+ channels worldwide.