“I am a sucker for people who seem to do what they do just for you (me).” The artist and writer Joe Brainard dashed off this thought in 1969, in a letter to his friend and fellow-poet Bill Berkson. Though Brainard was referring to Judy Garland, he could very well have been describing himself, and what he called his desire “to try to please.” People-pleasing has a bad artistic reputation—it’s more common to imagine serious artists driven by an uncompromising inner vision—but he made a poetics of it. A central figure of the so-called second generation of the New York School—the loose group of artists and poets who reshaped the city’s artistic landscape in the nineteen-fifties and sixties—Brainard wrote, drew, assembled, and painted first to delight his friends. By doing so, he infused his work with traces of his effervescent personality. His work demonstrates the power of art made specifically for another, and delivered as a gift.

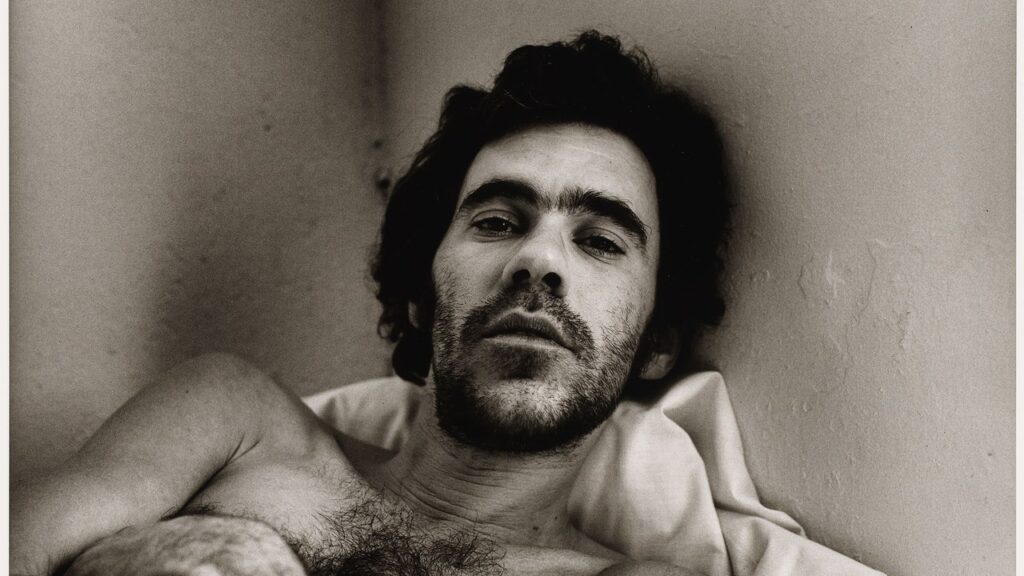

Brainard’s work was often born from direct collaboration—illustrating a collection of John Ashbery’s poems, for example, or inviting poets to make comic strips with him—and from the drift of everyday life. His œuvre includes breezy chronicles of his friends’ social lives, odes to the cigarettes he smoked (at one point, Brainard consumed more than four packs a day), and collages that moved effortlessly between Pop and the personal, many of which he gave to friends. Self-portrait is a frequent genre for Brainard, too, but his are of a particular kind, less memento mori and more playful remembrances—Polaroids for his friends to place in their wallets. A new collection of Brainard’s letters, “Love, Joe,” edited by the scholar Daniel Kane, offers glimpses of this constant play and productivity. Brainard is eager for friends to see his work but just as eager to enlist them in making it: in one letter to the poet James Schuyler, Brainard entreats him to “please save anything you run across that has anything to do with bananas.”

From Brainard’s teen years on, his writings were diaristic, seemingly spontaneous compositions, in which he let his mind follow the flux of his feelings and observations. They might incorporate his doodles, or describe the objects in his immediate vicinity (“why toes”), or chronicle a bus ride to Vermont or a trip to Bolinas, in Northern California, to visit the poetic circles of the West Coast. Even if sometimes messy, they are free of pretense. The fun of being in Brainard’s head is the sense (simulated or not) that he isn’t trying to do anything in particular, and so neither need you. As one comic-poem preaches, “People of the World, Relax!”

Brainard is perhaps best known today for “I Remember,” a book he published in 1970, although additions like “I Remember More” were to follow. Considered his masterpiece, the book is exactly what one expects: an extended flow of brief recollections, all beginning with that incantatory phrase “I remember.” To give a sample:

The entries are a mixture of sense memory, adolescent embarrassment, nostalgic fashions and foods, daydreams, and anything else that falls through the sieve of Brainard’s disarmingly casual syntax. Some are whimsical. Many are sexual, looking back ruefully on the desires Brainard felt before he understood himself as a gay man. Many entries strike a delicate balance between naïve and philosophical (“I remember wishing I knew then what I know now”). The steady stream of concrete recollections is broken up by occasional micro-stories, like the one about Elmslie, who would become Brainard’s lifelong partner and provider in a committed, if bumpy, relationship. Although it’s one of the great books for opening up at random (it’s nearly impossible for his memories not to trigger some of your own), when read in order, there is also a subtle pattern that can be felt as one memory brings another to the surface.

Perhaps it makes sense that Brainard, who prized spontaneity and present life, would make his greatest work by reflecting on the past. Ever self-deprecating, he was fond of saying that he had a terrible memory—perhaps lingering inside the same form for a prolonged period forced him to slow down, and, as he once wrote, generated an accuracy that couldn’t come from just letting his mind “gush.” “I Remember” is both a portrait of a period—mid-century America, outwardly self-confident but roiling with sexual misgivings and racial tensions—and a self-portrait, and it’s Brainard’s receptivity that creates an open channel between the two. It has inspired many imitations (including one by the French writer Georges Perec) and even become a kind of creative-writing exercise, but Brainard’s version remains the strongest, unified in its sensitivity and sensibility. He knew he was onto something universal inside the particulars of life, as he wrote to his friend and the poet Anne Waldman:

Brainard grew up in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in the nineteen-forties and fifties, a world away from the capitals of literary and artistic production. From early on, he showed himself to be a ferociously ambitious and talented visual artist. In high school, Brainard helped found a literary magazine, the White Dove Review, with his classmates Padgett and Richard Gallup. In its five-issue run, the magazine would solicit works by Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Robert Creeley, and other avant-garde notables—connections that would eventually draw them toward the center of the literary world. In Tulsa, Brainard and his cohort befriended the poet Ted Berrigan, who was working on his M.A. at Tulsa University through the G.I. Bill. Berrigan’s frenzied poetic output, championing the values of boldness and immediacy, would remain a lifelong influence for Brainard. (Berrigan’s most famous work, “The Sonnets,” would be dedicated to Brainard). After high school, Brainard did a brief stint in art school, in Dayton, Ohio, but ultimately absented himself by telling the school that his father was dying of cancer (he was not, but Brainard didn’t want to disrespect the school). In 1960, at the age of eighteen, he made the leap to New York City and immediately began a life of furious productivity and serious poverty.

For a brief time, Brainard and Berrigan shared an apartment with one bed, each taking turns working while the other slept. This modest beginning took place in the midst of late Abstract Expressionism’s supremacy (Willem de Kooning was a favorite), Andy Warhol’s Factory, the countercultural music of artists like the Fugs, and the plentiful readings and parties of a vibrant downtown scene. Living among poets, Brainard began his first forays into writing, which were published in Berrigan’s journal C, and also in other small presses and publications that were the lifeblood of the period’s innovative writing. At that time, writers like Ashbery and Frank O’Hara were helping to establish a new idiom in American poetry, something serious without self-seriousness: the new poetry was open to the city’s rhythms, irreverent but tender—and clearly, if not openly, gay. (Berrigan’s other influence would be to help introduce Brainard to amphetamines, which would power his prolific output for years, especially in collage, as he sorted through thousands of tiny scraps and images in his loft.)

In a circle best known for the mixing of poets and painters, perhaps no one was more at its center than Brainard, accomplished in both media. Everyone knew one another, dined with one another, loaned money to one another, slept with one another (though it would take Brainard a few years to come to terms with his sexuality as a gay man, he later embraced it). And, perhaps most important, they created for one another. This dynamic is sometimes referred to by scholars as “coterie poetics,” a term associated with the idea that writing within an in-group, and not primarily for the public, can grow a unique body of work. Like plants in a greenhouse, shelter from the rougher elements outside lets artists thrive in dialogue; the particular circumstance makes for something that can’t be recreated elsewhere. The coterie is also a way of looking at artistic production that thinks more collectively—we might instead see Brainard not so much as a singular personality as one station in a network of intimacies. These days, the coterie also seems like a garden to which it is difficult to return. In an internet-mediated cultural world, artists are left exposed to the elements of the wider “discourse,” without much choice for such nurturing enclosures.

Brainard often strived to be open in his art, and openness allowed him to adhere to everything and everyone he encountered. “Love, Joe” offers a window into these connections, showing how much Brainard’s personal life overlapped with his art. Probably no other writer’s letters so closely resemble his published work, and vice versa. The collection offers plenty of voyeuristic thrill—Andy Warhol, Alex Katz, and Fairfield Porter, along with the poets John Ashbery, James Schuyler, and Bernadette Mayer, are just a sampling of his illustrious address book. Though Brainard often downplayed his intellectual gifts, the letters capture some of his more candid opinions about his contemporaries, including Barnett Newman (“everything I don’t believe. . . . He is like death”) and Francis Bacon (“He’s so melodramatic, and corny!”). Among the collection’s best offerings are its hints of parties past (seeing the Velvet Underground in 1966), gossip (on sleeping with Allen Ginsberg: “I find him sexy not one bit, and so I couldn’t even get it up. However, we did a bit of Tibetan meditation”), and the rhythms of calm days spent swimming and sunning in Vermont. Brainard’s mind moves like a collagist’s, laying offbeat observations on top of heartfelt confessions. A serious discussion of color with Schuyler quickly becomes a meditation on Brainard’s malignant toenail.

If Brainard’s rich social world gives the impression of someone more famous for his life than his art, he also has a formidable body of work to show for himself. Brainard’s practice as a visual artist was extremely varied, and included drawings and comics, collage and assemblages, and more traditional oil paintings. An insouciant humor was never far from his work, as in his lewd reinterpretations of Ernie Bushmiller’s “Nancy” comics or in assemblages made with copious cigarette butts. Nor was he afraid of beauty, as can be seen in his delicate drawings and collages of flowers. Though Brainard quickly became well-known in New York, he was disappointed with the poor sale of his work outside the city. In an interview with the poet Tim Dlugos, he observed that “A lot of people would know who I am, but they wouldn’t really know what I did. . . . People want to buy a Warhol or a person instead of a work. My work’s never become ‘a Brainard.’ ” Business sense was perhaps a factor, too: he could startle his friends with the shockingly low prices at which he was willing to sell his work. For Brainard, art wasn’t quite a business, even though he often admitted his love of spending money. Friendship grew more important than art—the latter was the vehicle that allowed him to meet, know, and delight his loved ones.

Premium IPTV Experience with line4k

Experience the ultimate entertainment with our premium IPTV service. Watch your favorite channels, movies, and sports events in stunning 4K quality. Enjoy seamless streaming with zero buffering and access to over 10,000+ channels worldwide.