President Buchanan and the Election of 1856

The factors that shaped the 1860 Election became evident shortly after the 1856 Election. The Democratic nomination of James Buchanan over Stephen Douglas was largely orchestrated by James Slidell from Louisiana, who would play a significant role during Buchanan’s presidency. Following Buchanan’s victory over Douglas for the nomination, Douglas pledged his support to Buchanan in order to defeat John Fremont, the inaugural nominee of the Republican Party. Douglas anticipated having a say in patronage matters post-election, particularly regarding cabinet positions for two of his associates from the West. However, Slidell obstructed these appointments, having been granted authority over such decisions alongside Senator Bright of Indiana. The relationship between Douglas and Buchanan soured over the contentious Lecompton Constitution, leading to a fierce rivalry. By the time Douglas sought re-election as Senator in Illinois in 1858, Slidell had already purged many of Douglas’s allies from federal positions.

The Dred Scott Decision

Another pivotal element influencing the 1860 Election was the Dred Scott decision rendered by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1857. This ruling invalidated the Missouri Compromise of 1820, effectively legalizing slavery across all U.S. territories. The Court’s determination that the Constitution safeguarded the institution of slavery and that formerly enslaved individuals could never attain American citizenship heightened the existing sectional tensions. As a result, the election of 1860 was poised to further illuminate the stark divisions between those advocating for the abolition of slavery and those intent on preserving it.

Stephen Douglas and Popular Sovereignty

While the term “popular sovereignty” is closely associated with Stephen Douglas in contemporary discussions, it was neither his invention nor his original concept. The term gained a negative connotation due to its association with the contentious issue of slavery. The idea was first proposed by Michigan Senator Lewis Cass, who also had presidential ambitions tied to this principle. By the year 1848, Cass had established himself as a prominent figure in American politics, leading to his selection as the Democratic Party’s candidate for the presidency. The party believed that his stance on slavery would resonate with a diverse electorate.

Cass’s advocacy for popular sovereignty meant that the residents of a territory would have the authority to determine the legality of slavery within their borders. While this approach garnered some support, it also raised concerns among many Americans who viewed it as ambiguous and potentially disruptive to the delicate balance between slave and free states. This apprehension contributed to Cass’s defeat in the presidential election, where he lost to Zachary Taylor, a Mexican War hero known for his reluctance to express clear opinions on contentious issues, including slavery. After his electoral defeat, Cass returned to Michigan, where he continued to serve as a U.S. Senator until 1857, when he was appointed Secretary of State under President James Buchanan.

In 1854, the Kansas-Nebraska Act, championed by Stephen A. Douglas, introduced the concept of popular sovereignty to the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. This legislation empowered the settlers of these territories to determine for themselves whether to permit slavery within their borders, effectively nullifying the Missouri Compromise, which had previously established a geographical boundary for the expansion of slavery based on latitude.

Douglas’s initiative aimed to organize the Nebraska territory and bring it under civil governance. However, southern senators raised concerns since the area was situated north of the 36°30’ latitude line, which would classify it as a free state according to the Missouri Compromise of 1820. To secure support from the Southern faction, Douglas suggested the creation of two distinct territories—Kansas and Nebraska—while also repealing the Missouri Compromise. This arrangement allowed the settlers to decide the status of slavery in their territories, with the expectation that Kansas would lean towards being free and Nebraska would be more accommodating to slavery, thus preserving the political equilibrium.

Douglas himself was not a slaveholder, though his wife was. His political position was that it mattered not to him whether a state or territory was free or slave as long as that had been popularly decided. He maintained that the status of a state or territory—whether free or slave—should be determined by the vote of its citizens rather than by federal intervention. This belief led him to advocate for a compromise on the contentious issue of slavery, viewing it as a pragmatic approach to address the political turmoil surrounding the topic. His key contribution was the promotion of popular sovereignty, which allowed the residents of territories to vote on the legality of slavery within their borders.

Douglas argued that the decision regarding slavery should rest with the people living in the territories, rather than being dictated by the federal government. By framing the issue in terms of democratic choice, he aimed to navigate the divisive question of slavery without taking a definitive stance for or against it. While this approach seemed like a reasonable compromise at the time, it ultimately proved detrimental to Douglas’s political aspirations, as it alienated various factions and diminished his support.

The legislation had unforeseen consequences, particularly the repeal of the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which had previously prohibited slavery in Kansas. This change galvanized anti-slavery advocates in the North, leading to the formation of the “anti-Nebraska” movement, which eventually evolved into the Republican Party, dedicated to halting the spread of slavery. Additionally, the influx of both pro- and anti-slavery settlers into Kansas to influence the vote resulted in violent confrontations, culminating in a brutal conflict known as “Bleeding Kansas.”

The Lincoln-Douglas Debates

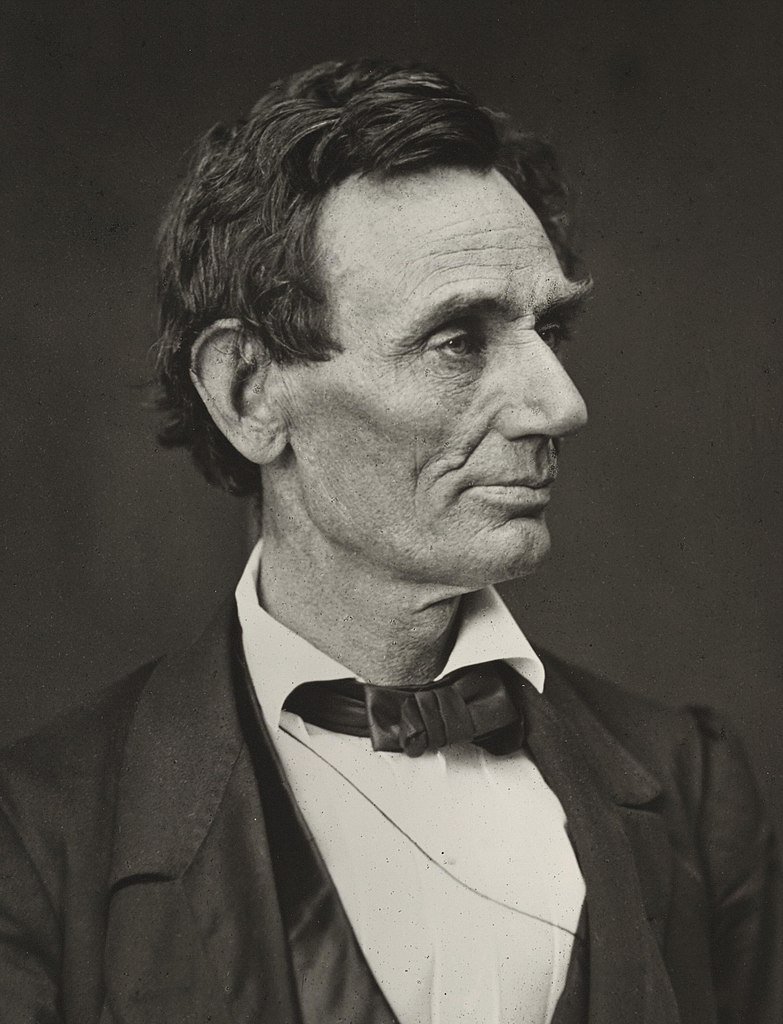

n 1858, Senator Douglas sought re-election in Illinois, facing off against Abraham Lincoln, a circuit lawyer and former congressman. During the Lincoln-Douglas debates, Lincoln focused on the concept of popular sovereignty, which ultimately placed Douglas in a precarious situation. His stance on slavery began to alienate Southern Democrats who perceived him as insufficiently supportive of the institution.

Lincoln’s perspective on slavery was rooted in moral opposition, yet he recognized that immediate abolition was not a feasible solution. He aimed to navigate a middle ground regarding the contentious issue of slavery. Upon receiving the Republican Party’s nomination for the Senate in 1858, Lincoln asserted that the nation needed to reach a definitive conclusion on the matter, expressing skepticism about the practicality of popular sovereignty with his famous assertion that “a house divided against itself cannot stand.”

This viewpoint became central to Lincoln’s campaign, as his debates with Douglas significantly elevated his profile in national politics. The discussions not only highlighted the deep divisions within the country regarding slavery but also positioned Lincoln as a formidable figure in the political landscape, setting the stage for his future leadership.

At their debate in Freeport, Lincoln challenged Douglas on the legality of a state or territory determining the status of slavery, given the Dred Scott decision had already addressed this issue. In his response, Douglas articulated the “Freeport Doctrine,” asserting that while he cared about the outcome of votes on slavery, he believed it was the prerogative of white citizens to make that determination. His position was that the state government could determine the implementation of Dred Scott by legislating or not enacting local authority and passing additional laws. This was the very definition of nullification, which had been the basis of the Tariffs Crisis 25 years before. Douglas seemed to hold the view that slavery was on the decline and had reached its limits, as it was primarily profitable in regions suitable for cotton and rice cultivation. He argued that slavery would not expand into areas where the climate and soil were unsuitable for these crops. Furthermore, Douglas maintained that the slavery issue should be approached as a local community matter rather than a constitutional one.

Although Douglas emerged victorious in the election, he ultimately fell prey to the very political dynamics he aimed to eliminate from territorial governance through his promotion of popular sovereignty. His actions were not evaluated based on their original intent but rather through the lens of the ongoing power struggle between the North and South, particularly concerning the expansion of slavery. Despite Douglas’s aspirations, the territories remained mere instruments in a broader political conflict, illustrating the complexities and challenges of addressing the slavery issue in that era

The Cooper Union Speech

Stephen Douglas was poised to become the Democratic nominee for president in 1860. He strategically positioned himself to attract support from both northern and southern constituents, presenting his stance as a means to end slavery for the North while simultaneously appealing to the South’s desire to preserve it. Abraham Lincoln recognized that the Freeport Doctrine was merely a political maneuver and understood the necessity of demonstrating that Douglas lacked genuine support from either faction. Additionally, Lincoln sought a compelling response to the Dred Scott decision to rally northern sentiment.

On February 27, 1860, Lincoln articulated his views in a pivotal speech at the Cooper Union in New York City. This address elevated him from a regional politician to a formidable contender for the presidency, as he presented a principled argument against the expansion of slavery and the enforcement of fugitive slave laws. His position was grounded in legal reasoning and reflected a politically moderate stance for the era. In his speech, Lincoln highlighted that at least 21 of the 39 signers of the Constitution believed that Congress should have the authority to regulate slavery in the territories:

“I defy any man to show that any one of them(the Founding Fathers) ever, in his whole life, declared that, in his understanding, any proper division of local from federal authority, or any part of the Constitution, forbade the Federal Government to control as to slavery in the federal territories. “

Although not as widely recognized as many of Lincoln’s other statements, these particular words showcased his political acumen and played a crucial role in securing his nomination for the Republican Party. Lincoln adeptly shifted the focus of the debate from the legality of slavery, which was constitutionally sanctioned at the time, to the issue of its expansion into new territories. This strategic pivot resonated with the centrist factions within the Republican Party, who were eager for a stance that sought to limit slavery’s reach while allowing it to remain where it already existed. Lincoln believed that by restricting slavery’s expansion, it would eventually wither away.

In his address, Lincoln raised significant questions about whether the Constitution actually barred the Federal Government from regulating the spread of slavery, or if it enshrined slavery as a permanent institution, effectively treating enslaved individuals as property devoid of rights. He argued that the Founding Fathers had envisioned a role for Congress in overseeing matters of enslavement. By referencing the signers of the Constitution who later voted to impose regulations on slavery, Lincoln illustrated that even prominent figures like George Washington had taken legislative action to control the institution.

As a result of Lincoln’s arguments, Douglas found himself politically outmaneuvered. In the Southern states, Douglas had championed the idea of popular sovereignty as advantageous to their interests, but Lincoln’s assertions exposed this stance as disingenuous. Meanwhile, in the Northern states, Douglas had attempted to align himself with anti-slavery sentiments, despite being the architect of legislation that supported slavery. This contradiction undermined Douglas’s credibility and highlighted the effectiveness of Lincoln’s strategic approach.

1860 Democratic Convention

The Democratic Party convened its convention in Charleston, South Carolina, during April and May of 1860. At this juncture, the party was in disarray; despite being the only truly national political entity, it failed to present itself as a unified front. The deep divisions over the issue of slavery were evident, with Southern Democrats advocating for its expansion while their Northern counterparts vehemently opposed this stance. The rift within the party had been brewing long before the Charleston meeting, primarily fueled by the rivalry between supporters of Stephen A. Douglas and those aligned with President James Buchanan, particularly figures like John Slidell. Southern senators, including Jefferson Davis (Mississippi) , Yancey (Alabama), and Rhett (South Carolina), rallied against Douglas’s Freeport Doctrine and his notion of Popular Sovereignty, deeming them insufficiently supportive of Southern interests. This internal discord ultimately culminated in a divisive split when Douglas arrived at the convention lacking the necessary backing for his nomination.

During the Democratic National Convention, Slidell collaborated with Alabama’s William Lowndes Yancey to obstruct the nomination of Douglas. As the specter of secession loomed, Slidell aligned himself with the more radical elements known as the “fire eaters.” His actions were pivotal in the fracturing of the Democratic Party, which had far-reaching implications. The division within the party not only weakened its position but also facilitated the rise of Abraham Lincoln, whose election might have been improbable had the Democrats managed to maintain their unity.

The events surrounding the 1860 Democratic National Convention serve as a critical moment in American political history, illustrating how internal conflicts can lead to significant electoral consequences. The inability of the Democratic Party to reconcile its differences over slavery not only fractured its base but also paved the way for the emergence of a Republican president. This period marked a turning point, highlighting the profound impact of party unity—or the lack thereof—on the trajectory of national politics.

The conflict regarding the official stance on slavery led to the withdrawal of numerous delegates from Southern states prior to the selection of a candidate at the convention. Although Senator Douglas garnered significant support from the delegates, he fell short of the two-thirds majority necessary for nomination, a threshold that his adversaries had deliberately established. Southern Democrats declined to back him due to his refusal to endorse a pro-slavery agenda. In protest, many delegates exited the convention, resulting in an insufficient number of remaining delegates to secure Douglas’s nomination, ultimately leaving the convention without a chosen candidate.

Northern Democrats convened for a second convention in Baltimore, Maryland, from June 18 to 23, although many Southern delegates were absent. During this gathering, the Democrats nominated Stephen A. Douglas, who won decisively against John C. Breckinridge, the current vice president from Kentucky. In an effort to reconcile the factions within the party, the convention initially approached Senator Benjamin Fitzpatrick of Alabama for the vice presidential nomination, but he declined. Ultimately, they selected Herschel V. Johnson, a former U.S. senator and governor of Georgia, to join Douglas on the ticket.

Southern Democratic Convention

Discontented Democrats, primarily from the South, staged a second walkout during the Baltimore convention when two replacement delegations were seated. They left the convention and met on their own, where they nominated John C. Breckinridge for president, with Senator Joseph Lane of Oregon as his vice-presidential candidate. Both Stephen A. Douglas and Breckinridge asserted their positions as the legitimate Democratic nominees. In June, Yancey and a faction of staunch supporters convened in Richmond to reaffirm Breckinridge’s nomination. President Buchanan endorsed this ticket, as Breckinridge had served as his Vice President and was an advocate for slavery and states’ rights.

Breckinridge proposed a federal mandate that would permit slavery in the territories, mirroring the existing laws in the states, provided that the local populace supported it, thereby safeguarding the rights of slaveholders to maintain their property.

Breckinridge, a two-term congressman from Kentucky, was a notable ally of Stephen Douglas during the 1856 election. Opting not to seek a third term, he turned his focus to horse breeding and legal practice. Following Douglas’s defeat at the 1856 convention, Breckinridge’s name emerged as a potential vice presidential candidate to appease the faction that had lost. However, this created tension with Buchanan, who viewed Breckinridge unfavorably due to his previous support for both Pierce and Douglas, whom Buchanan considered political adversaries. Despite their earlier friendship, the Lecompton controversy ultimately severed ties between Breckinridge and Douglas, allowing Breckinridge to rise in prominence as Buchanan’s presidency faltered in 1860.

At this juncture, a significant number of southern Democrats were not in favor of secession. Southern Unionists opposed the idea of breaking away from the Union. Some of these individuals chose to fight for the Union during the Civil War. Notably, several Confederate leaders, including Alexander Stephens, who would later become the vice president of the Confederacy, initially resisted the notion of secession, advocating instead for the benefits of remaining part of the Union. They held out hope that President Lincoln would adopt a conciliatory stance regarding the issue of secession. However, following the events at Fort Sumter, many shifted their allegiance to the Confederate States of America. Although Slidell initially belonged to this group, he ultimately aligned himself with the secessionist cause.

Southern Unionists can be divided into two distinct categories. Conditional Unionists typically supported the unrestricted expansion of slavery or at least favored the principle of Popular Sovereignty, advocating for the Federal government to allow the Southern states to secede peacefully. In contrast, Unconditional Unionists remained steadfastly loyal to democratic principles, regardless of the electoral outcomes. This latter group played a significant role in the Civil War, contributing approximately 200,000 troops from the South to the Union army, demonstrating their commitment to the Union despite the prevailing sentiments in their region.

The onset of the war led to noticeable fractures within the party, which undoubtedly contributed to the challenges faced in 1860. The War Democrats, a faction of Northern Democrats, were in favor of continuing the fight in the Civil War. While the majority of Northern Democrats remained committed to the Union following the secession of the Southern states, the War Democrats expressed their support for the war but were critical of the economic policies implemented by the Republicans and President Abraham Lincoln’s early actions, including the suspension of habeas corpus and the detention of dissenting publishers and politicians.

In the lead-up to the 1864 presidential election, the War Democrats allied with Republicans to establish the Union Party, which ultimately renominated Lincoln for the presidency and selected War Democrat Andrew Johnson from Tennessee as his vice-presidential candidate. This group consisted of Democrats who were in favor of the war effort aimed at preserving the Union. Notable figures among the War Democrats included Benjamin Butler, who would later switch parties, and Edwin Stanton, who also changed his political allegiance.

On the other hand, the Peace Democrats, represented by individuals like George Pendleton and Clement Vallandigham, advocated for a peaceful resolution with the Confederacy, even if it meant accepting disunion. Often referred to as “Copperheads,” these Democrats opposed the war and sought a negotiated settlement that would involve concessions to the South, allowing it to rejoin the Union. The term “Copperhead” was first introduced by the New York Tribune on July 20, 1861, symbolizing a deceptive and treacherous approach, akin to the snake that strikes unexpectedly.

The Republican Convention

“I am not bound to win, but I am bound to be true. I am not bound to succeed, but I am bound to live by the light that I have. I must stand with anybody that stands right, and stand with him while he is right, and part with him when he goes wrong.”

— Abraham Lincoln

The Republican convention took place in Chicago from May 16 to 18 at the Wigwam. Established in the mid-1850s following the disintegration of the Whig Party, the Republican Party primarily opposed the expansion of slavery into U.S. territories. While a significant number of its members advocated for the complete abolition of slavery, the party adopted a more pragmatic approach, refraining from calling for abolition in states where slavery was already entrenched. This moderate position focused on preventing the spread of slavery, although some delegates were in favor of its total eradication.

As the convention commenced, New York Senator William H. Seward appeared to be the frontrunner for the nomination. However, he faced considerable competition from several notable figures, including Ohio Senator Salmon P. Chase, Pennsylvania Senator Simon Cameron, Edward Bates from Missouri, and Illinois’s favorite son Abraham Lincoln, who was a popular candidate among local supporters.

During the first ballot, Seward garnered the most votes but fell short of the necessary majority for nomination by about 59 votes. The second ballot saw a tightening race between Seward and Lincoln, ultimately leading to Lincoln’s nomination on the third ballot. Additionally, Senator Hannibal Hamlin from Maine was selected as Lincoln’s running mate, solidifying the ticket for the upcoming election.

Of all the Republican candidates who were running for President in 1860, Lincoln stood out as the most unrefined and least experienced, possessing a notably sparse resume. His political career included a single term in Congress, during which he faced defeat in two Senate elections in Illinois, a state characterized by its western prairie. Lacking both administrative and military experience, Lincoln’s appearance was also unconventional; he was often noted for his ill-fitting attire and somewhat disheveled look. However, history reveals that he may have been one of the most articulate figures of his time, and with the benefit of hindsight, we can recognize that his skill as a persuasive orator was a significant asset. Observers of his speeches remarked on his awkwardness and the high pitch of his voice, yet his compelling narrative resonated with the public: he was the embodiment of the self-made man, having emerged from humble beginnings in a log cabin through sheer determination and intellect, rather than through the privileges of wealth or elite education.

The prosaic truth is that he might have been nominated simply because he was the least offensive candidate. He was a shrewd politician, first and foremost. His political positions were in the center of the party, and that was his precise political intent. Seward, who had been the Governor and Senator from New York, and Chase the Governor and Senator from Ohio, were abolitionists; and Bates, an elder statesman from Missouri, was conservative on the slavery issue, being from a border state that wasn’t inclined to overturn slavery. In that sense, Lincoln was a safe choice for the general election. Importantly, unlike the others, he had made no enemies along the way. Each had people that didn’t want him as the President and Lincoln’s strategy was superb. He said to the supporters of each one of those men, “If you can’t get your first love, come to me as your second love.” He also played his cards skillfully: he didn’t attack any of the others, while they were all busy attacking one another.

Lincoln demonstrated considerable political acumen, bolstered by a network of allies who actively supported him during the convention. Six months prior, his associate Norman B. Judd had journeyed to New York to advocate for Chicago as the venue for the gathering, engaging with influential figures like Thurlow Weed. The decision to select Chicago was influenced by the perception that Illinois posed no significant challenge to Seward’s candidacy. Judd effectively communicated this perspective, suggesting that Illinois, lacking a clear frontrunner, could serve as a suitable compromise location. Once the convention was confirmed for Chicago, Judd facilitated discounted train tickets for attendees traveling to the city.

In addition to promoting Chicago, Judd skillfully orchestrated the seating arrangements for the convention. He strategically placed New York and other states firmly aligned with Seward to the right of the podium, while Illinois and delegations that were either opposed to or indifferent about Seward were positioned to the left. This arrangement created a central section occupied by reporters, which effectively obstructed New Yorkers from engaging with undecided delegates during the sessions. As a result, Lincoln’s supporters enjoyed greater access to those delegates who were uncertain, while Seward’s team faced significant challenges in swaying them.

LINK: https://thirdcoastreview.com/2023/05/26/review-against-all-odds-the-lincoln-miracle-inside-the-republican-convention-that-changed-history-by-edward-achorn/

Thanks to a resourceful convention team working behind the scenes, Lincoln successfully garnered support and fostered the impression of a popular movement. Justice David Davis, who served as the presiding judge of the Illinois 8th Circuit, played a pivotal role in this effort. Having been a close friend of Lincoln and a fellow practitioner in the same legal circuit, Davis took on the role of campaign manager. He incentivized delegates with promising job opportunities in exchange for their votes, ultimately orchestrating Lincoln’s triumph over rivals Seward and Chase. Without Davis’s strategic influence, Lincoln’s ascent to prominence might have remained a mere footnote in history.

Ward Hill Lamon, a lawyer within the same 8th Illinois Circuit, held opposing views on abolition and leaned towards Southern sympathies. Despite their ideological differences, he and Lincoln forged a strong friendship. Lamon’s notable presence made him a recognizable figure, and he played a crucial role in rallying support for Lincoln at the convention. To ensure a favorable audience during the critical balloting, Lamon resorted to printing counterfeit tickets, allowing Lincoln’s supporters to fill the convention hall. Meanwhile, Seward’s camp, overly confident in their chances, celebrated the night before and found themselves inebriated and distracted, leading to a missed opportunity.

As the convention unfolded, the dynamics shifted dramatically. While Seward’s supporters were preoccupied with their parade outside the hall, Lincoln’s backers, armed with duplicate tickets, gained entry and filled the venue. This strategic maneuvering resulted in enthusiastic cheers for Lincoln every time his name was mentioned, creating an atmosphere that suggested he was the preferred candidate among the delegates. In stark contrast, Seward’s supporters, who had been unable to enter the hall, could not muster the same level of enthusiasm, undermining their candidate’s position as the frontrunner. The scene painted a clear picture of Lincoln as the people’s choice, swaying the delegates in his favor.

The Constitutional Union Party

The Constitutional Union Party emerged in 1859 as an effort to bridge the growing sectional divide in the United States, drawing together former Whigs and members of the Know-Nothing Party. This coalition nominated John Bell, a former senator from Tennessee, for president, and Edward Everett, the former president of Harvard University, for vice president. Their platform was particularly attractive to voters in the border states, as it sought to sidestep the contentious issue of slavery and instead emphasize loyalty to the U.S. Constitution.

Comprising mainly discontented Democrats, Unionists, and former Whigs. It was also comprised of former Know-Nothings, especially Millard Fillmore’s 1857 American Party. The Constitutional Union Party convened for its inaugural meeting on May 9, 1860, called together by Senator John J. Crittenden of Kentucky, a former prominent Whig. At Crittenden’s request, fifty former and current members of Congress met in Washington, D.C. in December 1859, where they agreed to form a new party dedicated to preserving the union and avoiding debates over slavery. This is the same Crittenden who would advance a compromise solution to secession in early 1861.During this gathering, they officially selected John Bell as their presidential candidate and Edward Everett as his running mate. The party’s formation was a response to the political turmoil of the time, aiming to present a united front amidst the fractious political landscape.

The party positioned itself as a champion of law and constitutional order, deliberately refraining from taking a definitive stance on slavery or states’ rights. Instead, they pledged to uphold the Constitution and maintain the Union, seeking to avoid the polarizing debates surrounding slavery that threatened national unity. Nevertheless, Bell proposed a compromise regarding slavery, advocating for the extension of the Missouri Compromise line across the nation, which would legalize slavery in new southern states while prohibiting it in northern territories, in hopes of attracting voters disillusioned by the Democratic Party’s internal conflicts.

The site has been offering a wide variety of high-quality, free history content for over 12 years. If you’d like to say ‘thank you’ and help us with site running costs, please consider donating here.

Premium IPTV Experience with line4k

Experience the ultimate entertainment with our premium IPTV service. Watch your favorite channels, movies, and sports events in stunning 4K quality. Enjoy seamless streaming with zero buffering and access to over 10,000+ channels worldwide.