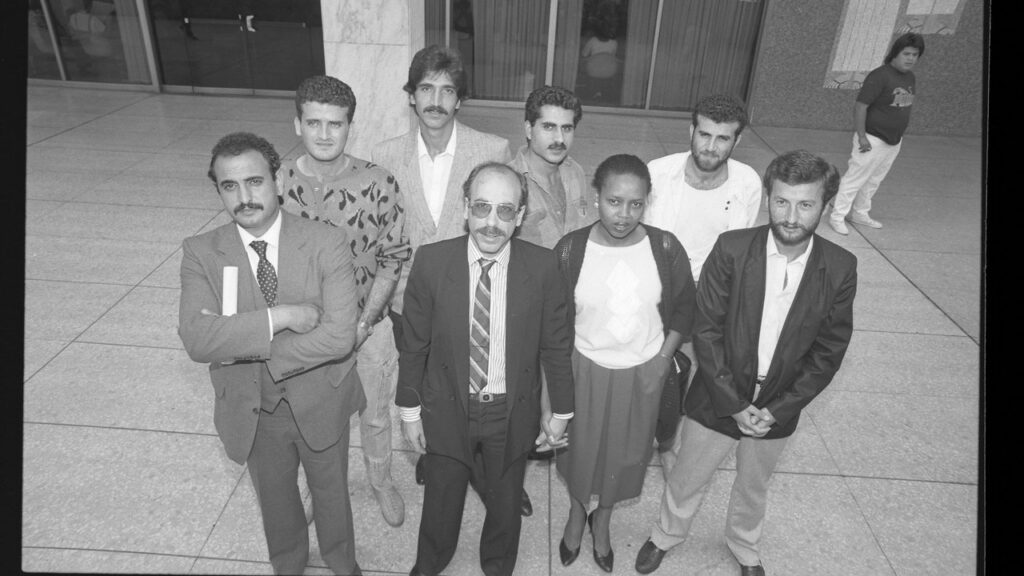

Nearly forty years ago, immigration officials in Los Angeles arrested eight young immigrants—seven Palestinian men and the wife of one of them, a Kenyan. The immigrants were mostly students. Two were permanent residents; the others were on student visas. They had been involved in pro-Palestinian activism. The government charged them all with being associated with a group that advocated the doctrines of world Communism, a justification for deportation dating back to the McCarran-Walter Act, of 1952, a Cold War relic.

I agreed to join the team representing the group, who became known as the L.A. Eight. At the time, I was one of the few practicing attorneys in the country with experience defending a communist deportation case. (This was, after all, the nineteen-eighties, not the nineteen-fifties.) I had recently represented the writer Margaret Randall, a U.S.-born citizen who had obtained Mexican citizenship while married to a Mexican poet, thereby losing her American citizenship, according to the U.S. government. In 1984, after their divorce, she returned to the United States, got remarried, and applied for permanent residency in America. The government denied the application and sought to deport her under the McCarran-Walter Act, arguing that her writings—she was a prolific author of oral histories, journals, and poetry—advocated the doctrines of world Communism. After a trial in which Randall was cross-examined about a literary magazine that she co-edited and a piece of writing in which she praised her three-year-old son for becoming “communist” as he had learned to share his toys, an immigration judge ordered that she be deported. But we won the case on appeal, when the Board of Immigration Appeals ruled that Randall had not, in fact, lost her U.S. citizenship when she became a Mexican citizen. As a U.S. citizen, she could not be deported, no matter how many “doctrines of world Communism” she advocated.

The arrests of the L.A. Eight, on a similar charge, followed a three-year F.B.I. investigation that had begun as the city prepared to host the 1984 Olympics. Looking for potential terrorist threats, the F.B.I. identified a group of young Palestinian activists. F.B.I. agents reported on their teach-ins and protests, monitored the literature they distributed, recorded license plates of individuals who attended their meetings, surveilled the activists for extended periods, and sent at least one undercover agent to attend a haflis, or annual public community dinner, that the group helped organize. The agent’s report stated that although he could not speak Arabic, it was clear from the tone of the music and the speeches that the event was a fund-raiser for terrorism. Ultimately, as the F.B.I. director at the time, William Webster, testified, the Bureau concluded that the individuals had committed no crimes, let alone terrorism.

But the F.B.I. nonetheless urged immigration authorities to deport them, not because they had engaged in any criminal activity but because they were effective activists. The F.B.I. characterized the group’s protests as “anti-Israel” and “anti-Reagan.” The agents singled out Khader Musa Hamide, a green-card holder, whom they described as the group’s ringleader, because he was “intelligent, aggressive, dedicated, and shows great leadership ability.”

We challenged the constitutionality of the “world Communism” deportation provision, and in 1989 a federal court declared that the provision was unconstitutional. The court ruled that the First Amendment protects all persons in the United States, including noncitizens. Since a citizen could not be punished for advocating world Communism, a noncitizen could not be deported for that reason. In our argument, we relied on a 1978 Supreme Court case, First National Bank v. Bellotti, that had extended First Amendment protections to corporations. The Court had reasoned that the First Amendment by its literal terms protects “speech,” not particular speakers, and does so in the interest of insuring a robust public debate for listeners, regardless of the source of any particular speech. Corporations have speech rights, the Court maintained, because we all have an interest in the speech they create. If corporations have First Amendment protection for that reason, we argued, surely noncitizens do, too. The district court in L.A. agreed, and Congress in 1990 repealed the “world Communism” deportation provision that was the basis of the case against the L.A. Eight.

But the case continued in immigration court. Congress enacted a new law rendering those who provide “material support” to a terrorist organization deportable, and the government amended its charges to include that provision. Federal courts blocked the deportations for many years, on the ground that, even if now charged under other provisions, our clients were impermissibly singled out for their political speech and associations, while noncitizens supporting the Contras in Nicaragua and the Mujahideen in Afghanistan were not deported. Selective prosecution based on constitutionally impermissible reasons, such as speech or race, has long violated the Constitution. The Supreme Court eventually reversed that selective-enforcement claim, ruling in 1999 that the defense isn’t applicable to an immigration case. The Supreme Court therefore returned the case to immigration court, where finally, in 2007, a judge dismissed the case, calling it “an embarrassment to the rule of law,” and the George W. Bush Administration declined to pursue an appeal. While the case was pending, the L.A. Eight grew older, some married and had children, and some became citizens. They have worked in affordable housing, civil engineering, construction, and the food industry, among other jobs. They had to spend more than two decades defending their right to remain here simply because they advocated for Palestinian self-determination. But since their case, immigration authorities have not sought to deport anyone for mere speech.

Until now. When Homeland Security agents arrested the recent Columbia graduate student Mahmoud Khalil for his role in leading pro-Palestine protests at the university, the arguments seemed eerily familiar. As two of the L.A. Eight did, Khalil holds a green card, authorizing him to remain here permanently. Like those activists, he is accused of leading protests with which the government disagrees. And, as with the L.A. Eight, the government argues that it can punish him for speech that would plainly be constitutionally protected for a U.S. citizen. The White House press secretary claims that Khalil “organized group protests” and “distributed pro-Hamas propaganda.” Donald Trump posted on Truth Social that his Administration would seek to deport anyone engaged in “pro-terrorist, anti-Semitic, anti-American activity.”

But the First Amendment protects the right to protest, to distribute pro-Hamas literature, and even to make “pro-terrorist, anti-Semitic, and anti-American” statements. The Court has held that it protects the right of the Klan to burn crosses and call for revenge against African Americans, the right of Nazis to march in Skokie, Illinois, and the right to burn an American flag.

The Administration has said it will invoke a little-used immigration law empowering the Secretary of State to order the deportation of any noncitizen whose “presence or activities” would have “serious adverse foreign policy consequences.” That provision was designed with high-level diplomats in mind, such as when the government is deciding whether to give a visa to a political leader charged with war crimes. The notion that pro-Palestine protests on a single college campus have “serious adverse foreign policy consequences” is absurd on its face. If that were the case, the United States could deport literally thousands of students across the country who participated in protests of the war in Israel and Gaza. And allowing deportation in these circumstances would be unconstitutional, for it would violate what the Supreme Court has called the “bedrock principle” of the First Amendment: “that the government may not prohibit the expression of an idea simply because society finds the idea itself offensive or disagreeable.” That principle brooks no discernable distinction between citizens and noncitizens who live among us. ♦

Premium IPTV Experience with line4k

Experience the ultimate entertainment with our premium IPTV service. Watch your favorite channels, movies, and sports events in stunning 4K quality. Enjoy seamless streaming with zero buffering and access to over 10,000+ channels worldwide.