Many filmmakers display undue faith in their ability to depict ways of life far outside their own experience. This blithe self-confidence is particularly egregious in depictions of distant history, where imagination inevitably courts fabrication. The Croatian director Igor Bezinović confronts this problem boldly and brilliantly in “Fiume o Morte!” (“Fiume or Death!”) by showing his process. He combines nonfiction elements with fictionalizations of historical events—and reveals the behind-the-scenes creation of these reënactments, turning the work into a documentary about its own making. The film, which will screen on April 4th and 5th in the “New Directors/New Films” series at both MOMA and Film at Lincoln Center, is centered on an astounding true story that took place in Bezinović’s home town of Rijeka, and his telling emphasizes both his personal connection to the saga and the strangeness of dramatizing it.

The film focusses on a tumultuous period between 1919 and 1921, when the Italian-nationalist poet Gabriele D’Annunzio, in defiance of his own government, led a convoy of rebel soldiers into Rijeka—a town, on the Adriatic Coast, which had a large Italian minority and was then widely known by its Italian name, Fiume. Quickly consolidating power, D’Annunzio ruled Fiume as a dictator. The results were oppressive for the city and—because D’Annunzio’s exploits won the admiration of the younger, even more ambitious Italian nationalist Benito Mussolini—catastrophic for the world. Bezinović presents the story of D’Annunzio’s autocratic rise, reign, and fall in a way that’s as unusual as it is revelatory. He gathers a teeming array of archival material and a teeming cast of actors—mostly nonprofessionals, many recruited via person-in-the-street interviews—to re-create the archival depictions of the occupation.

Bezinović, far from shrugging off the peculiarity of the procedure, calls attention to it, with humorous barbs aimed in multiple directions—including at himself. The casting interviews start out as informational ones, as he stops passersby to ask whether they know of D’Annunzio. Many, especially younger ones, don’t. Those who do—mainly elders—have little good to say of him; one calls him “a horrible fascist” and adds, “They’re still around today.” Amid these spontaneous discussions of the former dictator, Bezinović asks middle-aged men who happen to be bald, like D’Annunzio, whether they’d be willing to portray him. Bezinović also pays special attention to those who speak Fiuman, the town’s then prevalent, now rare Venetian dialect—not least because he integrates the language into the soundtrack, sharing the duties of voice-over narration with the participants whom he films.

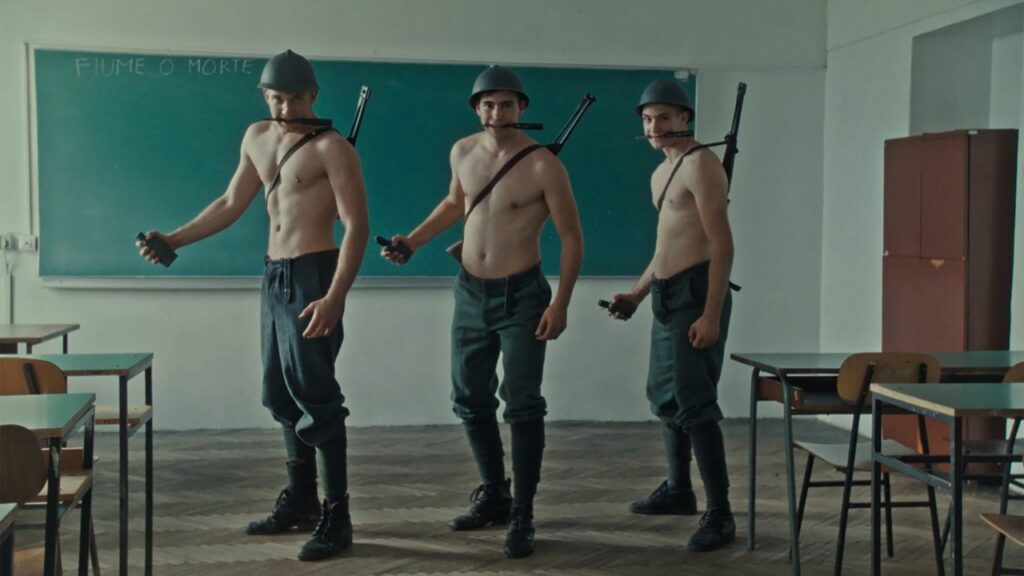

Throughout, Bezinović enlists other amateurs in smaller roles. Young men are invited to play soldiers; upon locating the hotel (now a private dwelling) where D’Annunzio spent a night en route to the takeover, Bezinović recruits the woman of the house to play the chambermaid ministering to the traveller. Some of these scenes require drastic transformations: the storefront that housed D’Annunzio’s favorite tavern, reputedly the site of his and his cronies’ licentious revels, is now a nail salon, which, with the consent of its owner, the cast and crew turn into a set-like reproduction of the long-ago haunt. But at other times there’s a seemingly deliberate dissonance, as when the would-be dictator drives into town at the wheel of a snazzily modern red convertible sports car. In one memorable sequence, D’Annunzio is played by a professional guitarist who, after acting out a crucial showdown with an Italian general, provides his own raucous musical accompaniment to the aftermath.

One crucial aspect to Bezinović’s antic yet earnest restagings is that they do more than merely represent the events seen in archival visual sources. He also replicates the compositions, the framings, of the originals, engaging in his own form of directorial reënactment. It’s a fraught gesture, because some of the sources that he mimics are themselves implicated in the movie’s grim history. Many of the archival images are the work of D’Annunzio’s own so-called Photography Section, which, as Bezinović relates, took ten thousand pictures; the director wryly comments, “It was crucial to him that the occupation be remembered, as it is to us who are making this film.” Bezinović thereby shares in the political risks of the project, putting himself into the same ethical position, behind the camera, as the actors impersonating D’Annunzio in front of it.

The movement of memory goes both ways—not only does “Fiume o Morte!” conjure the past, it pulls the events of the past into the present tense, conveying an eerie feeling of witnessing them occurring in real time. Bezinović’s sense of the city’s history involves a native’s intimacy with its locations, its monuments, its traditions. The director visits sites that figured prominently in D’Annunzio’s reign, such as a present-day apartment building that was then a prison, and reveals surviving traces and artifacts of the regime. He counts off the years, from the late nineteenth century through the First World War, by filming the floors of buildings in which the year of construction is set in mosaics. By means of a simple and ingenious twist of editing, Bezinović makes his reënactments point both ways, too: he frequently puts his own restagings ahead of the sources he’s copying, as if visually proclaiming his astonishment that the seeming absurdities he himself puts onscreen are the undeniable realities of D’Annunzio’s time.

Bezinović brings to the fore the racial hatred on which D’Annunzio’s iron-fisted, thin-skinned rule was based, and the ethnic cleansing that it involved. The movie cites his first visit to Fiume, in 1907, when he attended a play in which, the voice-over says, “Slavs are referred to as ‘thieves’ and Croatians as ‘wolves.’ ” The strutting demagogue, who declared “whoever is not with us is against us,” meted out violence on nationalistic pretexts: when Italians were killed in the nearby city of Split during clashes between supporters of D’Annunzio and the local population, he ordered the physical destruction of non-Italian businesses and institutions throughout Fiume. (The attacks, too, are reënacted, to jolting effect, at their actual sites.) When Italy sought a referendum in Fiume on D’Annunzio’s government, he first agreed but, realizing that it was coming out against him, sent troops to disrupt the vote, which was then ignored. Bezinović notes that the otherwise thoroughly documented regime somehow failed to photograph these doings—then dramatizes them nonetheless.

Bezinović also visually apostrophizes D’Annunzio’s fanatical nationalism with footage of a current-day rally, with chants and fireworks, sparked by the rivalry between Rijeka and Split’s soccer teams: an everyday expression of the identitarian pride so easily weaponized by opportunists. Sports played a role in the authoritarian ethos imposed by D’Annunzio, and so did culture—he created a code of conduct that required his troops to excel in a wide range of athletic skills, singing and dancing, and the odd practice of imitating human and animal voices. The aesthetic regimen for body and mind was matched by a tune that dominates the soundtrack of “Fiume o Morte!”—a marchlike song called “Giovinezza” (“Youth”), which, under Mussolini, became the official Italian Fascist anthem.

The endgame of fanatical youth is cruel. The city’s residents tired of D’Annunzio’s reckless rule, and his bellicose posturing and expansionist maneuvers discomfited the Italian monarchy. The dénouement came on Christmas Eve, in 1920, when the increasingly isolated D’Annunzio declared war on his native Italy. The playful enthusiasm that his soldiers had hitherto displayed in martial training and sporty festivities, and the esprit de corps forged in their common cause, gave way to their bloodied corpses; the film’s depictions of their gory stillness, in full color, come as a shock.

D’Annunzio slunk back to Italy the following month with a bombastic air of satisfaction, of a mission accomplished, and lived in palatial isolation. (Mussolini supposedly likened D’Annunzio to a bad tooth: “You either pull it out or cover it in gold.”) The palace, Bezinović notes, is now a tourist attraction. What “Fiume o Morte!” makes plain is the ease with which a motivated demagogue and a coterie of followers, taking advantage of a divided citizenry, can ride waves of complicity and complacency to absolute power. As one actor, preparing to impersonate the dictator, tells Bezinović, “I think it’s a lovely game that has to be approached with a great seriousness.” The movie’s historical re-creations, however derisive, are chilling. The story’s immediacy is intensified not only by clever dramatics but by its echoes of current events, for which D’Annunzio provides—depending on one’s views—a cautionary tale or a cookbook. ♦

Premium IPTV Experience with line4k

Experience the ultimate entertainment with our premium IPTV service. Watch your favorite channels, movies, and sports events in stunning 4K quality. Enjoy seamless streaming with zero buffering and access to over 10,000+ channels worldwide.