When President Lyndon Johnson signed the Wilderness Act, on September 3, 1964, he called it one of the “most far-reaching conservation measures” ever approved. The bill established fifty-four wilderness areas, most in the American West, which, together, encompassed more than nine million acres. As the act famously put it, in these areas “the earth and its community of life” were to remain “untrammeled by man.” Homes, roads, cars, and even bicycles would therefore be prohibited.

There was, however, a gap in the law, one big enough to drive an earthmover through—or, really, several hundred. To win passage of the measure, which had gone through more than sixty drafts in the course of eight years, its sponsors agreed to a compromise. For the next twenty years, mining claims would still be honored. Anyone who held such a claim could blast a hole through a spot that otherwise was protected.

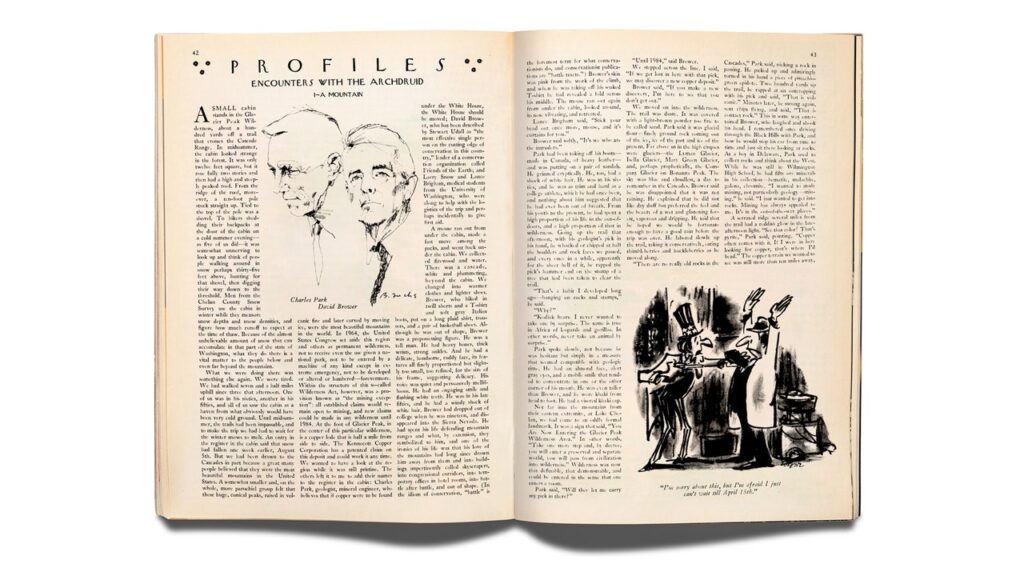

A few summers after Johnson signed the act, John McPhee hiked out to Miners Ridge, in Washington State’s Glacier Peak Wilderness, where an enormous copper mine was planned. With him were two men who did not like each other. One was David Brower, the Sierra Club’s longtime head. A tall man with delicate features, Brower had once been an accomplished mountaineer, but by the time of the hike he had spent more years trying to defend remote places than he had exploring them, and he was out of shape. There was, McPhee noted, “a fold across his middle.”

The other man was Charles Park, a geologist on the faculty at Stanford. Like Brower, he had spent much of his life in the mountains, but his interest in the landscape was less disinterested. Park had hunted for silver in Nevada, gold in Alaska, and iron in the Chilean Andes. So often had he laid hold of what he was seeking that some of his friends—perhaps jokingly, perhaps not—attributed to him occult powers.

The trail to Miners Ridge wound through some of America’s most spectacular scenery—snow-covered peaks, riffled streams, meadows spangled with wildflowers. Trudging along, Brower and Park admired the view and exchanged shots.

“Geologists go into the field because of love of the earth and of the out-of-doors,” Park says at one point.

“The irony is that they go into wilderness and change it,” Brower retorts. He declares the proposed mine an abomination: “If we’re down to where we have to take copper from places this beautiful, we’re down pretty far.”

“Minerals are where you find them,” Park counters. “It’s criminal to waste minerals when the standard of living of your people depends upon them.”

Who wins this back-and-forth? It’s hard to say. Though the piece is nominally about Brower—the Archdruid of the title, who returns in subsequent installments in the three-part series—Park is an equally compelling character and, quite possibly, a better debater. Brower is a crusader, Park a pragmatist.

“People seldom stop to think that all these things—planes in the air, cars on the road, Sierra Club cups—once, somewhere, were rock,” Park tells McPhee, out of Brower’s earshot.

McPhee’s evenhandedness harks back to an era when reasonable people could disagree. (When the Wilderness Act finally got to the floor of Congress, it passed with bipartisan support.) But it would be a mistake to see in his restraint something as straightforward as an effort at objectivity.

McPhee has been writing for The New Yorker for nearly sixty years, on subjects as varied as oranges, basketball, plate tectonics, barges, roadkill, and, most recently, writing itself. In a 2015 essay titled “Omission,” he spoke up on behalf of reticence: “When you are deciding what to leave out, begin with the author. If you see yourself prancing around between the subject and reader, get lost.”

Much of the art of “Encounters with the Archdruid” lies in the way that McPhee manages to be both there and not there. He bathes his aching feet in the water. He recalls other trips he has taken with Brower and, separately, with Park. He searches for copper-bearing rocks, and, when he finds them, gets excited. But he never reveals whose side he is on. When it comes to the great question of the piece—to mine or not to mine—he gets out of the way. ♦

Premium IPTV Experience with line4k

Experience the ultimate entertainment with our premium IPTV service. Watch your favorite channels, movies, and sports events in stunning 4K quality. Enjoy seamless streaming with zero buffering and access to over 10,000+ channels worldwide.