It’s a familiar image on church banners and tourist souvenirs: the double-headed eagle soaring over the memory of Byzantium. Yet the real story behind this symbol is far more complex — and far older — than many realize.

By Georgios Theotokis

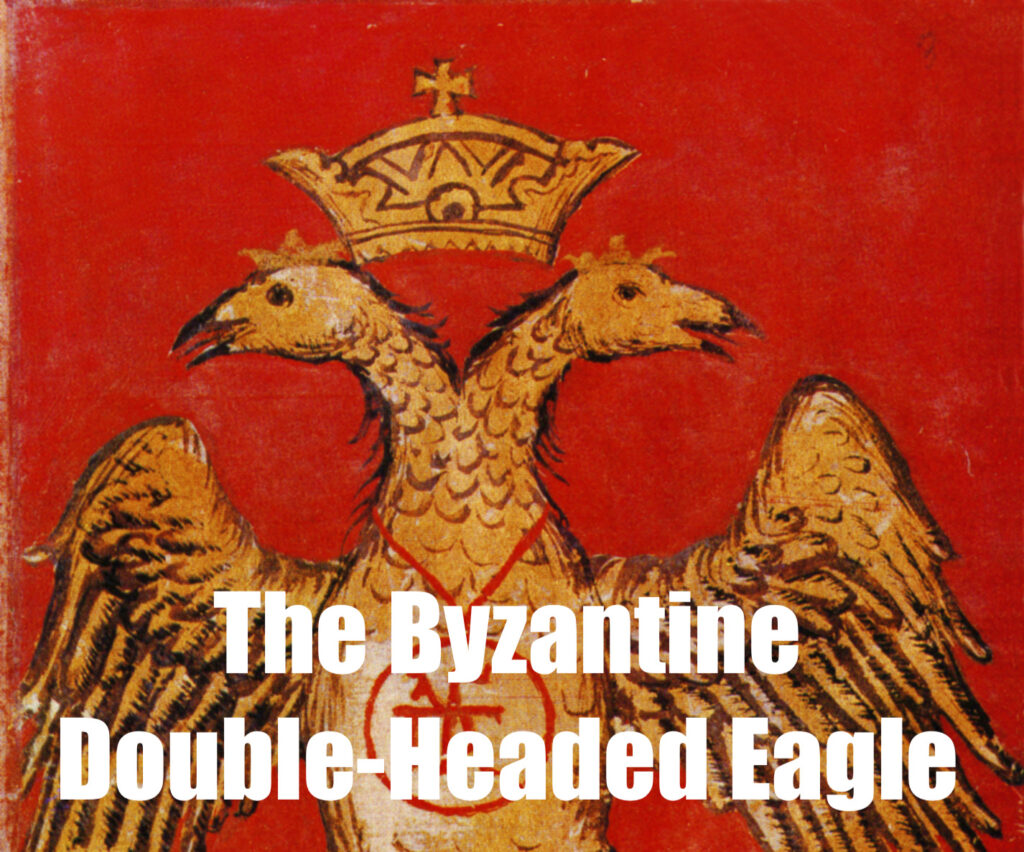

In Byzantine heraldry and vexillology, the double-headed eagle (or double-eagle) is a charge associated with the concept of Empire — the heads represent the dual sovereignty of the emperor both in secular and religious matters and/or dominance over both East and West. After the Holy Cross, perhaps no other symbol has been associated more closely with the history and fate of the Byzantine Empire than the double-headed eagle motif, to the point that it has been engraved in modern imagination as being the ‘official flag’ of the empire up to its dying days in 1453. However, how accurate is this association, and how informative are our sources about it?

Symbols and insignia (Greek: σημεῖα) were various emblems with different symbolic significance for the audience, used to express the social and political position of an individual or an institution. These emblems should not be confused with heraldry, which provided a readily interpreted system of symbols to represent familial and individual identity, and came to connote aspects of privileged social status, patronage, and ownership.

Moreover, the use of heraldic insignia as a symbolic representation of families did not develop in Byzantium to the same extent as in the West before the Fourth Crusade. The broad range of images — Christ, the Virgin, the Cross, various saints — found on seals are, in fact, personal rather than familial. Following the Byzantine restoration of 1261, traces of heraldry can be found in the empire. Yet, different symbols and emblems held profound significance in the public imagination throughout Byzantine history — and perhaps the most well-known of them was the double-headed eagle.

It is easy to imagine that the history of the double-headed eagle, as depicted in flags and labara, or carved in church walls and colonnades, or in castle and palace gates, can be traced back to the imperial Roman single-headed eagle. An aquila, or eagle, was the standard of a Roman legion. Fixed to the top of a spear or pole, and usually made of silver or bronze with outstretched wings, the legionary aquila was probably of relatively small size, since a standard-bearer (signifer) under Julius Caesar is said in circumstances of danger to have wrenched the eagle from its staff and concealed it in the folds of his girdle.

These “eagle-bearers” (Greek: ὀρνιθόβορας) were still attested in the sixth-century military manual known as the Strategikon of Maurice (Book XII. B. 7, 11, 17). Their duties, according to George Dennis, were probably those of an aide-de-camp or orderly, and they were supposed to be unarmed. Eagle-topped sceptres were also a frequent feature of consular diptychs, and they can be seen in coins too until the reign of the emperor Philippicus Bardanes (AD 711–13).

Yet, the double-headed eagle has been depicted in various cultures and periods since at least the third millennium BC. That this motif appears on Hittite monuments in central Anatolia has been known since their discovery by Charles Texier in the early 19th century. Modern historians have argued that the monumental art of the Hittites was so impressive that it was copied by later peoples for their coats of arms.

The Hittite walled city of Alaca Hüyük was important as a ceremonial center during the 14th–13th centuries BC, and the double-headed eagle is prominently displayed on the eastern section of the Sphinx Gate, grasping two prey animals, likely hares. Both sections of the Sphinx Gate display the double-headed eagle supporting figures, although the inside face of the western section has been worn down so that the image is not as visible.

Recent research by Jesse D. Chariton has shown that the use of the double-headed eagle motif followed a westerly route from Mesopotamia to Anatolia sometime at the beginning of the second millennium BC. This is supported by a Babylonian seal impression, probably from the third millennium BC, which displays a double-headed eagle over a king. Sumerian literature may also shed light on the origin of the double-headed eagle in Mesopotamia. Of particular interest is the Sumerian thunderbird Imdugud, whose morphology in some representations shows a lion-headed bird grasping antelopes in its talons.

Therefore, there is clear evidence that ancient Near Eastern cultures had used the double-headed eagle motif for millennia before Rome or the Crusades.

To return to the discussion about its use in Byzantium: despite the common belief that the two-headed eagle was used as the official flag of the Byzantine Empire, there is absolutely no shred of evidence to support this claim!

The single- and double-headed eagles both appear from around the mid-12th century onward in the decoration of buildings built by members of the imperial Komnenos family. For example, a single-headed eagle can be found at the Theotokos Kosmosoteira in Pherrai, western Thrace, commissioned by the sebastokrator Isaakios Komnenos in 1152.

The double-headed eagle appears more commonly throughout the Palaiologan period, as in a well-known plaque from the Metropolis of Mystras in the southeastern Peloponnese.

However, this motif was not exclusive to Byzantium. We can see the two-headed eagle appearing in mosques, fortresses, palaces, and Anatolian Seljuk caravanserais as a magical (animistic) and protective symbol of strength. It was particularly prevalent during the reigns of the Grand Seljuk Sultans of Rûm, Alaeddin Keykubad I (1219–1237) and his son and successor Gıyaseddin Kay Khusraw II (1237–1246).

This usage declined sharply after the Battle of Köse Dağ in 1243, as many Seljuq traditions of pre-Islamic origin, including the depiction of animals, were abandoned.

The Palaiologan emperors used the double-headed eagle as a symbol of the senior members of the imperial family. The emperor is distinguished by his richly jeweled regalia, such as in the famous Athonite chrysobull of 1374 where Alexius III of Trebizond wears purple and jewels, while his consort’s garment is decorated with double-headed eagles.

Occasionally, a suppedion or cushion appears below the emperor’s feet, on which an eagle is represented, as in portraits of Michael VIII (reigned 1261–82; with single-headed eagles) or Andronikos II (reigned 1282–1328; with double-headed eagles).

The only occasion when the double-headed eagle appears on a flag is on the ship that bore Emperor John VIII Palaiologos to the Council of Florence, as mentioned by Sphrantzes and confirmed by its depiction on the Filarete Doors of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome.

Furthermore, the eagle (gold on a red background) was used by the semi-autonomous Despots of the Morea and by the Gattilusi of Lesbos, who were Palaiologan vassals married into the Palaiologos family. The relief at the Castle of Mytilene — under the Gattilusi from 1355 to 1462 — portrays the family cipher of the Palaiologoi (left), the Byzantine double-headed eagle (centre), and the Gattilusi coat of arms on its breast, alongside the eagle of the Doria family.

The presence of the double-headed eagle of the Palaiologoi in the Greek Empire of Trebizond (1204–1461) and the neighboring Greek principality of Théodoro in southern Crimea (which fell to the Ottomans in 1475) is little-known. Western portolans of the 14th–15th centuries use the double-headed eagle (silver or golden on red or vermilion) as the symbol of Trebizond rather than Constantinople. Single-headed eagles are also attested in Trapezuntine coins.

Other Balkan states followed the ‘Byzantine model’ — chiefly the Serbs, but also the Bulgarians and Albania under George Kastrioti (better known as Skanderbeg). After 1472, the eagle was adopted by Muscovy and then Russia.

The Ecumenical Patriarchate in Constantinople, Mount Athos, and Greek Orthodox Churches in the diaspora under the Patriarchate also use a black double-headed eagle on a yellow field as their flag or emblem.

Yet to attribute the double-headed eagle motif solely to Byzantium is erroneous. First, this motif had a multi-cultural history stretching back several millennia before the Byzantines inherited it through Rome. Second, there is absolutely no iconographical or literary evidence that associates the motif as the official device or flag of the Byzantine Empire.

Why this myth persists may be the biggest mystery of all!

George Theotokis received his PhD in History from the University of Glasgow (2010), specializing in medieval military history. He has published numerous articles and monographs on the history of warfare in Europe and the Mediterranean in the medieval and early modern periods, including The Art of War in Byzantium (Arc Humanities Press, 2024). He works as an Assistant Professor of European history at Ibn Haldun University in Istanbul.

Click here to read more from Georgios Theotokis

Subscribe to Medievalverse

Premium IPTV Experience with line4k

Experience the ultimate entertainment with our premium IPTV service. Watch your favorite channels, movies, and sports events in stunning 4K quality. Enjoy seamless streaming with zero buffering and access to over 10,000+ channels worldwide.