In 1887, New York’s infamous Women’s Lunatic Asylum on Blackwell’s Island received a new patient named Nellie Brown. She was a bit different from the other occupants there. As soon as she entered the doors, all of the intense acting out that had landed her there disappeared. That’s because Nellie Brown was really Nellie Bly, an undercover journalist on assignment for a newspaper called the New York World.

Bly faked her own insanity, fooling several doctors and a judge, to get sent to the institution. Blackwell’s opened as the New York City Lunatic Asylum in 1839 on what’s known today as Roosevelt Island. It was a state-run hospital housing poor patients. Tours of the facility were popular and seen as ways to make money and ensure patients were given the best treatment.

The complex was meant to house 1,000 patients, but by the late 1800s, Blackwell’s was severely overcrowded with nearly 1,600 people. Tourism ground to a halt, budgets were cut, and fewer doctors were able to provide care.

But most visitors were not able to see what was going on behind the walls. Bly’s reporting gave one of the first real accounts of the brutality and horrors female patients faced at asylums like it.

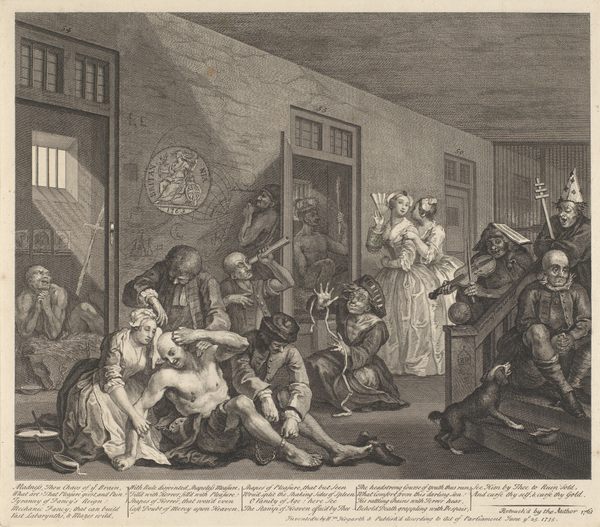

About 100 years earlier, institutions like Blackwell’s were built to essentially imprison the mentally ill and did not have mission statements intended to cure or treat them. Asylums across England and the U.S. became magnets for curious tourists who mostly went to gawk at patients as if participating in a spectator sport.

Practitioners running the asylums—who weren’t doctors at that point—had no training and believed mental illness was a disease of the body, not a condition of the brain. They used cruel and inhumane treatments that reflected this thinking, including blood-letting, ice baths, starvation, and corporal punishment. “Dangerous” patients were often chained to walls naked, and others underwent “rotational therapy”: spinning in a chair for hours to induce vomiting.

London’s Bethlem Royal Hospital, known as Bedlam, is one of the best-known asylums where tourism thrived. It opened in 1247 as a monastery, and by 1407 it was housing mental patients. Tourism began there in the early 1700s and continued well into the 18th century. Visitors paid a penny entrance fee to wander the wards.

Superintendents hoped that visitors would feel compassion for the patients and therefore donate to the hospital. The reality was most tourists were there simply to see—and often ridicule—patients.

“Looking at the patients made those on the outside feel privileged because they weren’t like them,” says Troy Rondinone, a historian at Southern Connecticut State University and author of Nightmare Factories: The Asylum in the American Imagination. “These were popular places to go, and they did have zoo-like, leering atmospheres.”

There were rules about what tourists could see, but supers couldn’t always control the exchanges with patients. Many patients didn’t seem bothered by the visitors, scholar and historian Janet Miron writes in Prisons, Asylums and the Public. Miron reports that some visitors to Blackwell’s in New York even suggested some patients seemed to like the company and attention. Many patients were social and answered tourist questions.

Others, however, hid in seclusion, shirking the intrusion and glares from strangers. These were the patients who suffered from asylum tourism, Miron writes.

The tourists experienced some slight mental discomfort, as well. One visitor to Bedlam reported hearing rattling of chains, drumming on doors, and patients ranting and singing so frighteningly, it could “put Hell in an uproar.”

“There was this false idea that patients would be cured,” Rondinone says. “But in reality, they were essentially trapped and stripped of all of their belongings, living in a place with iron bars on the windows.”

By the early 19th century, though, asylums began to change, and the use of “moral treatment” was on the rise. Mental illness was no longer considered a disease of the body, but was thought of as curable. An idea grew that if asylums were designed well and managed properly, conditions inside would improve. But tourism didn’t stop.

Contrary to the 1700s when visitors mostly went to witness the spectacles inside, Miron writes that 19th-century citizens considered tours as part of their duty “to improve the treatment of the insane.”

Hospital superintendents had to convince the public that the brutal treatments of the past were over. “Tourism was still about money but also about getting good press,” Rondinone says. “The hospitals were treating patients and ‘healing’ them and could ask for more money to ensure the hospitals stayed alive.” So tourism continued with less outright exploitation.

Asylums were such a firm part of the tourism industry that the hospitals were promoted in ads and tour books at the time. Blackwell’s was listed in the 1880 Miller’s New York As It Is guidebook.

“A visit to the several establishments on this island will well repay anyone interested in the efforts for ameliorating human suffering,” the guidebook author wrote. “The humane object of this institution is to separate vagrants from criminals, and to compel all to work who are able to do something towards their own support.”

There was a change in why the public toured asylums and what parts, too.

At the time, many asylums were built following psychiatrist Thomas Kirkbride’s design. Kirkbride believed that housing patients in an environment with fresh air and natural light would promote better health.

“Kirkbride was very proud of the design and wanted architects and visitors to see it and how it was healing people’s minds,” Rondinone says.

These asylums were massive structures that included two wings with corridors to allow sunlight and air ventilation. They had sprawling gardens that were designed to be sanctuaries for patients, but also to be part of their recovery. Occupational therapy was part of moral treatment, so patients could farm the land and tend to the grounds as part of their therapy.

In fact, the meticulously designed grounds were becoming huge draws for tourism.

“The approach to the Asylum from the southern entrance, by the stranger who associates the most sombre scenes with a lunatic hospital, is highly pleasing,” Miller’s New York As It Is guidebook stated. “The view from the top of it, being the most extensive and beautiful of any in the vicinity of the city.”

By the late 1800s, around the time Nellie Bly got herself committed at Blackwell’s, optimism surrounding moral treatment began to decline. It was the cusp of the Industrial Revolution in America and more immigrants were coming to the United States.

Soon state-funded asylums were full of impoverished people and immigrants who didn’t speak English. Superintendents were tasked with managing overcrowded facilities with little staff. Blackwell’s population swelled from 278 in 1840 to more than 1,300 by 1870. To save money, the hospital skimped on food. Manicured gardens and occupational therapy gave way to corporal punishment, restraints, and drugs.

“What you start seeing inside is mirroring [people’s] outside standings,” Rondinone explains. “If you were wealthy, you could pay and go to a nice sanitarium. If you were poor, you were put in a state hospital like Blackwell’s.” By the late 19th century, Blackwell’s and other asylums like it were full of the city’s lower classes.

By the time Bly was committed to Blackwell’s, stopping by an asylum wasn’t easy for tourists. Visits had become reserved mostly for wealthy females with charitable clout who considered the task as part of fulfilling her duties to society. Writings from these wealthy women at the time contradict what patients really experienced.

The affluent certainly didn’t see what Bly faced—and exposed to the public—which became a two-part series on the front page of the New York World. Bly started with the small things like the horrible food. Soup was spoiled. Tea “tasted as if it had been made in copper,” she wrote. Buttered bread and oatmeal were inedible.

She revealed how the building was freezing and how she and other female patients were subjected to regular beatings and torture, like ice baths.

“It was hopeless to complain to the doctors, for they always said it was the imagination of our diseased brains,” she wrote.

Bly admitted she never attempted to act insane while inside. She wrote “the more sanely I talked and acted, the crazier I was thought to be.” Bly ended up suspecting the treatments were making patients worse. “The insane asylum on Blackwell’s Island is a human rat-trap,” she wrote. “It is easy to get in, but once there it is impossible to get out.”

But Bly did get out, and her exposé for the newspaper shocked the public. Her pieces eventually helped lead to the kind of reform the watchful eyes of tourists never could.

“Around this time, cities were trying to allocate money for mental hospitals,” Rondinone explains, “but [Bly’s] series of articles definitely outraged people and led to a huge push for reform.”

Other reports confirmed Bly’s articles, and several months later, she published a book about her experience called Ten Days in a Mad-House.

However, for all its negatives, asylum tourism did have some positives. It may have helped educate the public about mental illness and showed what treatments did—and did not—work.

“The idea that they were curing people was a myth,” Rondinone says. “The truth was it was reform through enslavement, and that was very disturbing to people.”

Today, the only tours of asylums are those that are abandoned and turned into haunted houses. The patients are mercifully no longer present, but as far as society has come, the fascination in people’s minds is still there.

“I still don’t think asylum tourism says anything bad about us,” Rondinone continues. “I think it’s very human to be intrigued.” Sometimes that intrigue can lead to reform, other times it leads to abandoned tourism.

Premium IPTV Experience with line4k

Experience the ultimate entertainment with our premium IPTV service. Watch your favorite channels, movies, and sports events in stunning 4K quality. Enjoy seamless streaming with zero buffering and access to over 10,000+ channels worldwide.