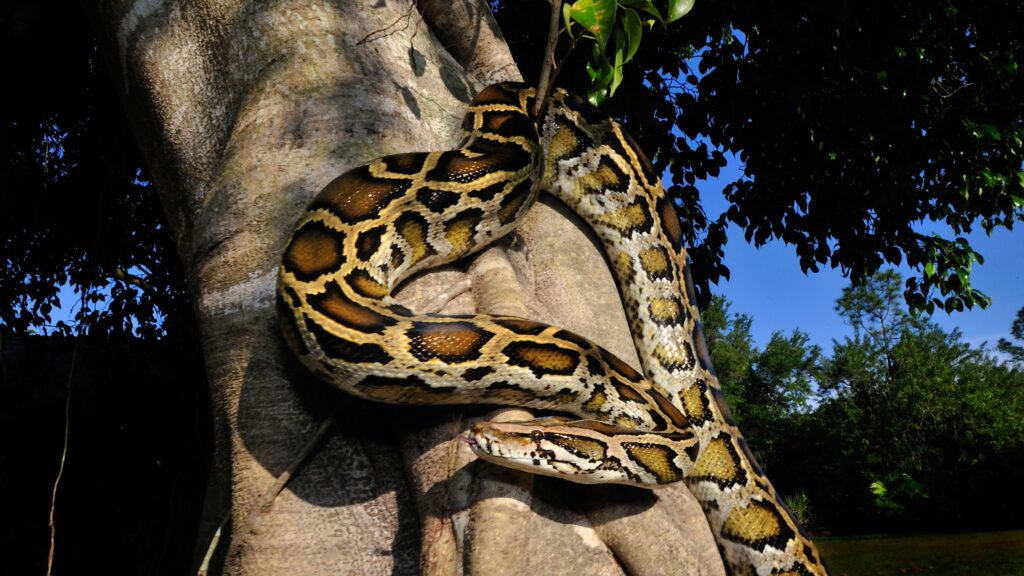

Fifteen years ago, a cold snap froze much of Florida’s wildlife to death — including many of the state’s invasive Burmese pythons (Python bivittatus). But in this excerpt from “Slither: How Nature’s Most Maligned Creatures Illuminate Our World” (Gand Central Publishing, 2025), science writer Stephen Hall reveals that a subset of these pythons were genetically predisposed to survive the cold, setting the stage for rapid evolution that could help the invasive snakes spread further into North America.

In early January 2010, a historic and prolonged deep freeze swept across the southeast United States, reaching all the way into the subtropical Everglades. Temperatures hovered around 50 degrees Fahrenheit (10 degrees Celsius) for 48 hours; on Jan. 11, thermometers in South Florida dipped as low as 24.8 F (minus 4 C). Most people remember it, if at all, for the frozen iguanas that dropped out of trees and photos of citrus trees encased in icicles, like some fugitive Minnesota winter carnival smuggled into the Deep South.

But to wildlife and invasive species experts, the Big Freeze marked the start of the Big Unplanned Experiment.

The immediate impact on the Burmese python population was clear. Carcasses of dead snakes littered roads; frozen specimens turned up in underground burrows; farther north in South Carolina, in the infamous “Where’s Waldo” python enclosure, all 10 snakes perished during the regional cold snap.

Researchers attributed the mass die-off to “maladaptive behavior,” meaning many snakes tried to bask above ground in the sun despite the frigid temperatures, rather than seeking thermal shelter in underground or aquatic burrows. Python “removals” — captures by hunters, which served as a rough indication of the general population — had peaked in 2009 in the national park but plummeted almost five-fold in the following two or three years. It all looked like good news, at first.

But population numbers were still lacking, and “models” are still just models. Genes are where the rubber of biology meets the road of environmental challenge, and this is when the geneticists entered the story. They were less interested in the many snakes that had died, and more interested in the few that had survived.

Like all snakes, Burmese pythons are ectotherms — they rely on warmth from the environment because they do not generate their own metabolic heat — so they have to develop biological tricks in their behavior or in their physiological resilience in the face of life-threatening cold to survive freeze events that do not occur in their native range. As the United States Geological Survey (USGS) overview put it, “some portion of the southern Florida population survived” the 2010 event, “and these snakes and their offspring make up the current population.”

By 2014, the number of python removals in Everglades National Park had returned to pre-freeze levels. In genetic parlance, the 2010 freeze was a “bottleneck event” — only a few squeezed through and survived. But the ones that did, in the biblical sense, went forth and multiplied.

Beginning around the year 2015, several researchers studying python genomes to understand their metabolism became curious about the after effects of the big freeze. Daren Card and Todd Castoe of the University of Texas at Arlington teamed up with Maggie Hunter of the USGS office in Fort Lauderdale to look for evidence of what is called rapid adaptation, which might be thought of as an up-tempo version of Darwinian evolution.

They examined the DNA of these survivor snakes to see if there were any genetic clues as to why certain pythons were able to withstand an extended freeze; more precisely, they compared the DNA of pythons that lived before the freeze event with the DNA of pythons that had survived to see if they could identify any differences that might explain the resilience of the survivors at the molecular level.

The short and disturbing (although not definitive) answer was: yes.

It turns out that the survivors seemed to share genetic changes in areas of their genomes known to control thermoregulatory behavior and metabolism. “We saw a lot of things that just fortuitously overlapped with a lot of the same sorts of pathways and genes that we were studying in parallel, in a much more controlled fashion, using more lab experiments in Todd’s work on Burmese pythons,” Card told me. “As we delved into them, we started to see a lot of genes that are involved in things like thermal tolerance.”

The findings, published in 2018, suggested that the survivors shared variations in their genetic makeup that seemed to confer greater cold tolerance and greater metabolic flexibility — two traits that Castoe’s lab had been investigating since 2011. These snakes were more inclined behaviorally to seek shelter in underground refugia to outlast the cold — a good adaptation to the environmental reality of occasional freezes. And the metabolic changes seemed to favor a behavior that encouraged smaller and more frequent meals — a good adaptation to the ecological reality that, having already decimated populations of large mammals in the Everglades, the pythons might need to modify their diet.

This is not definitive news — the study was small, no one (surprisingly) has followed up on it, and, as Card put it, researchers still only have a view from 30,000 feet of what happened on the genetic level in the pythons that survived the Big Freeze. Whatever it is, the genetic changes — or, more accurately, the selection for genes that enhanced survival — appears to have happened very quickly. And that is, possibly, very bad news. It suggests that the pythons are on the move, genetically as well as geographically.

The implication is that the 2010 freeze acted as a huge selection event, as evolutionary biologists put it — an environmental stress so dire, so extreme, that it has the effect of rapidly winnowing out individuals holding a bad genetic hand and “selecting” the lucky ones that hold winning genetic hands.

The freeze culled out individuals that were susceptible to cold temperatures and selected individuals that possessed, at the genetic level, some form of cold-hardiness. Those genes were presumably passed down — immediately, profligately and of course, cryptically — to their hundreds of offspring.

The suggestion of rapid adaptation in the Burmese python population in Florida again contradicts our traditional notions of evolution as a glacial process of genetic selection and refinement that requires millennia, eons and geological epochs. “We typically think of evolution as occurring over generally quite long time scales, on the order of several generations at the low end up to potentially thousands to millions of years,” Card said. “I think with a lot of the tools that we’ve developed more recently, especially in things like genomics, people have taken a harder look at how quickly evolution can occur… And generally, when you see such an extreme thing occurring, it really suggests that there’s very strong selection. Something’s happening.”

In fact, Castoe believes the importation of so many pythons from so many different regions of Asia — all packing in their biological luggage a wide variety of genetic variants, known as alleles, for their trip to North America — set the table for a rapid genetic adaptation. As Castoe put it: “If you’ve got a good amount of genetic variation, given strong selection, this can happen in a heartbeat. ‘If I’ve got the allele, what the hell am I waiting for? I ain’t waiting for nothing!'”

At a time when roughly 40% of Americans do not accept the notion of evolution, the pythons that survived the Big Freeze in Florida appear to believe in it 100%. The take-home genomics message from the snakes is that evolution is real, it’s apparently happening at blindingly fast speed, and it argues that the 2010 cold snap may have created a subset of pythons better able to survive cold temperatures — and thus better adapted to spread beyond the northern boundaries of its current range.

Excerpted from SLITHER: How Nature’s Most Maligned Creatures Illuminate Our World ©2025 Stephen S. Hall and reprinted by permission from Grand Central Publishing/Hachette Book Group.

Premium IPTV Experience with line4k

Experience the ultimate entertainment with our premium IPTV service. Watch your favorite channels, movies, and sports events in stunning 4K quality. Enjoy seamless streaming with zero buffering and access to over 10,000+ channels worldwide.