In late February, the Office of Management and Budget instructed all federal entities to align themselves with “the President’s America First foreign policy.” It required agencies and private institutions that receive government grants to conduct a kind of self-audit, to weed out foreign programs that do not promote “American prosperity by advancing capitalism, markets that favor Americans, competition for American partnership, and economic self-reliance.” There would be no more “global welfare mentality.” As part of the audit, any grantee receiving money for “foreign assistance” would have to answer the question “Does this project create measurable benefits for U.S. domestic industries, workforce, or economic sectors?”

U.S.A.I.D., the government’s primary conduit of development and disaster assistance abroad, was already being liquidated. The United States had withdrawn from the World Health Organization and the U.N. Human Rights Council; the State Department seemed more preoccupied with deportations than with diplomacy. Yet some international work remained possible inside agencies with a primarily domestic agenda. At the Department of Labor, for instance, grants were still funding nonprofits that educated migrant farmworkers about their rights to fair recruitment, and groups that tackled human trafficking in countries that export products to the United States, from Congolese cobalt to Colombian flowers. (The Tariff Act of 1930 bans imports of goods made by forced labor, and campaigns against such exploitation have been historically bipartisan.) The Labor Department’s Bureau of International Labor Affairs, or ILAB—which was created just after the Second World War—was still sending investigators to factories and training judges abroad to enforce labor provisions in various trade accords, including the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (U.S.M.C.A.), the update to the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) that Donald Trump negotiated in his first term. “This work is of interest to the Administration,” one ILAB employee told me. “That’s the thing I thought would save us.”

Lori Chavez-DeRemer, Trump’s new Labor Secretary, was sworn in on March 11th. She moved quickly to comply with the O.M.B. request—and with the Administration’s overarching objective of shrinking the federal government. Large posters of her, captioned “LET’S GET TO WORK,” went up in the elevators at D.O.L. headquarters, in Washington. Within days, she had cancelled a number of ILAB grants. She posted the news to X, boasting of having saved thirty million dollars “by eliminating ‘America Last’ programs in foreign countries like Indonesia, Colombia, Guatemala, Chile, & Brazil.” Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) account reposted it, writing, “Great job.” According to Business Insider, three DOGE employees were stationed at the D.O.L., including Miles Collins, who reportedly co-owns Pacific Fertility Center, a Los Angeles clinic that is being sued for employment discrimination for, among other things, denying a pregnancy-related medical leave. (Pacific Fertility Center did not respond to a request for comment.)

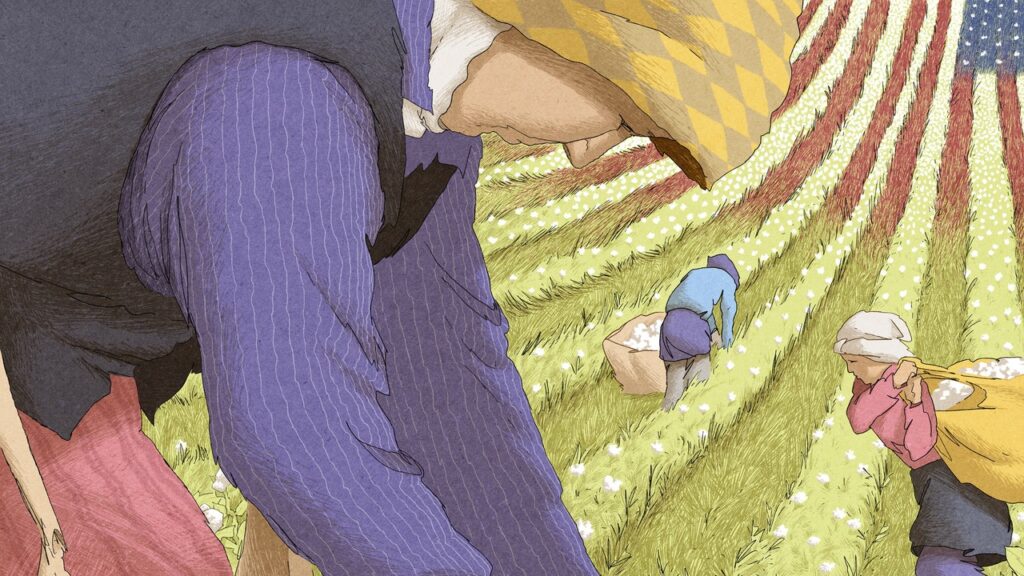

In late March, DOGE praised Chavez-DeRemer and the Labor Department for cancelling all remaining “ ‘America Last’ grants for $237M in savings.” These funds would instead go to the “AMERICAN Workforce,” the D.O.L. wrote on X, though Congress had specifically earmarked them for “programs to combat exploitative child labor internationally” and “programs that address worker rights” in countries with which the U.S. trades. “We learned this morning that the Department has taken a decision to immediately terminate all of ILAB’s existing grants,” Mark Mittelhauser, the associate deputy under-secretary who ran ILAB, wrote to some hundred and fifty employees of the bureau. Those in charge of administering and evaluating programs in dozens of countries were dumbfounded. There was an immediate stop to projects supporting collective bargaining in Mexico, addressing worker abuses in Southeast Asian fisheries, and reducing child labor and sexual exploitation in Madagascar’s mica mines. On X, the D.O.L. posted a cartoon meme deriding ILAB for “FUNDING UZBEKISTAN’S COTTON INDUSTRY.” In fact, ILAB and its grantees had advocated for years to target child and forced labor in that country, one of the world’s top cotton producers, so that American businesses weren’t undermined by an artificially cheap supply. The United States Fashion Industry Association and the American Apparel & Footwear Association wrote to Chavez-DeRemer, pleading for her not to end the program. Grantees such as the International Labour Organization, the Solidarity Center, and the American Institutes for Research made plans to lay off staff all over the world. A second ILAB employee told me, “We’re basically saying to the rest of the world, ‘Go ahead.’ It’s profitable for businesses to have supply chains that aren’t ethical, employing children, forcing people to work.”

Mittelhauser was abruptly placed on administrative leave in early April and marched out of D.O.L. headquarters. Chavez-DeRemer temporarily replaced him with her chief of staff, Jihun Han, who worked for Chavez-DeRemer when she was a member of Congress. (She was elected in 2022 and served one term.) Chavez-DeRemer sent an e-mail to employees at ILAB and three other sub-agencies—the Women’s Bureau, the Office of Public Affairs, and the Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs—urging them to consider early retirement or “deferred resignation,” in which employees are placed on leave for a period of months before their official separation. Mass layoffs would be coming soon. She later extended this offer to all of the D.O.L.

On the fifth floor of headquarters, ILAB staff cried in the halls. “Everyone was constantly fearing for their job,” a third, longtime ILAB employee told me. “They’ll show up one day, and their cards to get in will just be shut off—the mental fuck of the whole thing.” Meanwhile, the D.O.L. posted a gauzy head shot of Chavez-DeRemer, captioned “HAPPY BIRTHDAY, MADAM SECRETARY,” on X, and threw a party. Wine and flowers were set atop dark-blue tablecloths; Chavez-DeRemer’s photograph was projected on large monitors. The “Alt U.S. Department of Labor” account on Bluesky posted, “Does it get any more ‘let them eat cake’ than golf tournaments and birthday soirees?” (Trump had just returned from a golfing weekend in Palm Beach.) Employees scribbled “Resist” in the elevators and taped over the Chavez-DeRemer posters with a two-part meme of the singer Drake: in one image, he frowns and turns away from the phrase “Using taxpayer dollars to end unsafe working conditions”; in the other, he smiles and points approvingly at “Using taxpayer dollars to throw yourself a birthday party.” (Courtney Parella, a D.O.L. spokesperson, denied that it was a birthday party and said that whatever cake was there had been purchased by Chavez-DeRemer’s family.)

Yesterday, an hour and a half after The New Yorker e-mailed a list of fact-checking queries and requests for comment to the D.O.L., Han, the chief of staff, sent a memo to all department employees, warning them not to speak with the media. Doing so, he said, could lead to serious legal consequences, including “potential criminal penalties.” At least one employee has filed a complaint with the Office of Special Counsel, an agency that protects federal whistle-blowers, alleging an improper “gag order.”

Last week, the vast majority of staff in the D.O.L.’s contract-oversight division, the Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs (O.F.C.C.P.), either resigned or were put on indefinite leave. “We were given one hour of notice before being told we had to leave the office, and locked out of all D.O.L. systems,” an O.F.C.C.P. employee in California told me. In the past fiscal year, the division recovered $22.5 million for more than twelve thousand workers who had been discriminated against by contractors. “Some of those recoveries were for white males,” the employee added. The employee believed that the Administration and DOGE had targeted O.F.C.C.P. because of a pending “compliance review” of fair-employment practices at Musk’s Tesla plant in Fremont, California. That review was largely abandoned in early February. (Tesla recently settled a suit by a Black worker at the plant who said that racial slurs had been written all over the walls and that a manager repeatedly greeted employees by saying, “Welcome to the slave house.” Other suits are pending.) There is now almost no one left to make sure that private companies receiving billions of dollars from the government comply with civil-rights laws. Parella, the D.O.L. spokesperson, said that the changes at O.F.C.C.P. have “nothing to do with Elon Musk and everything to do with restoring merit-based opportunity.”

ILAB staff took an informal census of who would be leaving through deferred resignation and early retirement, and counted forty per cent of the bureau. Several employees told me that they had felt pushed out; they had no real choice. Teams within ILAB hosted get-togethers in person and online, to wish their colleagues goodbye. It wasn’t clear who would perform tasks that are required by statute: investigating and publishing annual reports on child labor and forced labor; coördinating with Customs and Border Protection to exclude imports produced by those means; enforcing labor provisions in the U.S.M.C.A. in collaboration with the U.S. Trade Representative. A fourth ILAB employee told me that she worried about her projects in Africa, where the bureau had funded trainings for workplace inspectors. “We think about the lives of people in other places in the world,” she said. “But the goal is also to benefit the U.S. in terms of both soft power and trade agreements.”

Trump’s erratic tariff policies were undermining trade pacts such as the U.S.M.C.A. The same day DOGE and Chavez-DeRemer cancelled all of ILAB’s grants, Trump had announced levies of twenty-five per cent on auto imports. His decision was praised by the United Auto Workers but criticized by trade economists for likely slowing down production and increasing prices. When Trump signed the U.S.M.C.A. into law, in 2020, he called it “the largest, fairest, most balanced, and modern trade agreement ever achieved,” and declared an end to “the NAFTA nightmare.” Many unions and labor experts agreed. Unlike NAFTA, the U.S.M.C.A. required forty to forty-five per cent of the contents of every imported vehicle to be made by workers who are paid sixteen or more dollars per hour. It was also the first trade agreement to include a “Rapid Response Mechanism” (very fast compared with the complaint process at the World Trade Organization) through which workers, unions, or businesses could complain of unfair labor practices in Mexico. “It’s a way to penalize or respond to companies who aren’t following Mexican labor law, when their goods are coming into the U.S.,” a fifth ILAB employee told me. The results have benefitted mining and manufacturing workers in more than thirty cases so far. In 2022, the Teksid Hierro auto-parts plant, in the state of Coahuila, a few hours’ drive from the Texas border, was required to rehire and compensate three dozen employees who had been fired for organizing; the workers went on to negotiate a nine-per-cent wage increase and safety improvements. In 2023, the Goodyear rubber factory in the central Mexican state of San Luis Potosí was mandated to hold an independent union election and pay workers $4.2 million in back wages and benefits.

Premium IPTV Experience with line4k

Experience the ultimate entertainment with our premium IPTV service. Watch your favorite channels, movies, and sports events in stunning 4K quality. Enjoy seamless streaming with zero buffering and access to over 10,000+ channels worldwide.